|

observer |

|

|

|

|

|

OTHER LINKS |

|

|

|

FIFA World Cup - Germany 2006.......Continuing our special coverage of the FIFA WORLD CUP Footy then and now

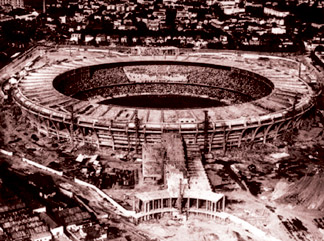

In his entertaining memoir, Refereeing Around the World, Arthur Ellis recalls the opening game of the 1950 World Cup in Brazil, an occasion which was also the opening day for the Maracana Stadium. Brazil were to play Mexico. The local mayor, a man cursed with the prolix way of the breed, gave a speech which was inflicted on the masses via a dodgy public address system. Such was the noise that the referee couldn't hear the speech and blew the whistle to commence the match in the middle of it. Now, a firing party who had been appointed to provide a 21-gun salute as the centre piece of the opening ceremony, panicked and got off their shots quickly, hitting the upper tiers of the new stadium and causing small amounts of concrete debris to dislodge and fall onto the people below. The gunfire provoked the release of hundreds of fireworks which spooked the doves of peace (or pigeons as Ellis insists they were) and soon the air was filled with gunsmoke and feathers, balloons, pyrotechnics and the screams of 150,000 lunatics. The game had scarcely settled when Brazil scored. And then all hell really broke loose. Local radio stations

Denied a clear shot of the celebrations, the ranks of photographers followed suit with a pitch invasion of their own. Brazil won 4-0 and the occasion was deemed an epic success. Sadly Germany this summer holds out no prospects of extra mural spontaneity. The media section of the tournament website trills with such promising developments as "Germany to Waive Noise Limit Laws!" and (be still my beating heart, this just in from Berlin) "Tower Sphere Turned Into Giant Football." It is, says the website, "time to make friends in Berlin". Fair enough. This will be the World Cup where the trains run on time. Where the matches kick off on schedule. Where the tyranny of the media mixed zone reaches new heights. Every World Cup breeds its own brand of dictator; ordinary men and women get handed an orange bib and as soon as they put it over their heads turn "keeping the passageway clear" into a life-changing personal philosophy. We worry about the Germans in this regard. (Our hero in this matter incidentally is Eric Cantona, who in Boston in 1994 found that he had suffered enough and promptly punched one of the orange bibs on the nose.) Whatever this World Cup brings it won't be as exciting a production as 1974. A Haitian player tested positive for doping . . . the Haitian team doctor helpfully offered his professional opinion that the player was too stupid to dope himself . . . the player then got beaten up by the officials of his own football association . . . an Argentinian player got arrested for assaulting a chamber maid . . . the fabulous Poles, surprisingly having prevented England from qualifying, transpired to be a gift that kept on giving. They came third . . . total football and those cranky, intellectual, Dutchmen . . . the Scots and the Billy Bremner v Jimmy Johnstone little ginger war . . . East Germany v West Germany . . . der Bomber and so on. This time there won't even be Keano. There won't even be a fuss about there not even being Keano. There won't even be an FAI. The spirit of the FAI survives though. Robert Schaefer, German police chief, recently announced his force's brainy wheeze for coping with hooligans. In trouble spots a policeman with a megaphone will describe "in the language of the pub" what is going on and what the police are doing. The idea is to soften the image of the police, make them less authoritarian to say, English, fans. Somebody asked Robert what languages the jive-talking megaphone cops would be available in. "Many of them (hooligans) will understand German. Right?" Worry not. The best excitement in Germany will be cloaked from view by the pencil thin men from the PR companies. Those of us who are there will watch from a distance, through a window of orange bibs and official press releases and wonder if it's worth being there at all. Then again. A moment, a fragment, an instant changes all that. To have been in Foxboro when an (artificially) pumped Maradona played his last World Cup game for Argentina against Nigeria or in the Velodrome when Bergkamp scored his unreasonably sublime goal against the Pumas four years later, or to have been in Seoul for the clap-happy progress of the South Koreans last time out, those moments made World Cup pilgrimages worthwhile. And smaller less visible moments nourished too. Once on a train to Lyon during France 98 we saw an elderly French man, who had been sitting quietly with his wife, stand up and hush a carriage full of fearfully drunk Scots. He closed his eyes and sang Sur La Pont d'Avignon as his wife gazed up at him and then the couple shared their tomato sandwiches with tattooed Glaswegians. Another trainOn another train once, Dutch and Mexican fans (the sole occupants) organised a mobile Mexican wave, each carriage standing up in turn and waving and cheering while the train lurched and lolled. We've been in bars crammed with dancing Brazilians, we've been shoehorned into shared cabs with muscular Nigerians, we've hidden behind bus shelters and walls from rioting Englanders and walked miles, lost in the company of Argentinians. Mostly we come home and, to paraphrase David Foster Wallace, we say that the World Cup was a supposedly fun thing we'll never do again. On the other hand the quadrennial venture outside the comfort zones of middle age provides a transfusion of adrenalin. In a universe where all forces drive us indoors into the sodium lit solitude of our TV rooms, there to text other humans as to wot we r doin, the World Cup gives us 31 days to go out and play, to rub shoulders and shake hands and put away our fears and prejudices. A true communal experience, classless and democratic, a celebration of the people and a simple game. There's nothing like the World Cup. There's nothing like being there.

FIFA World Cup TrophyWith the Jules Rimet Cup now in the permanent possession of Brazil after their third World Cup(tm) triumph in Mexico City in 1970, FIFA commissioned a new trophy for the tenth World Cup(tm) in 1974. A total of 53 designs were submitted to FIFA by experts from seven countries, with the final choice being the work of Italian artist Silvio Gazzaniga. He described his creation thus: "The lines spring out from the base, rising in spirals, stretching out to receive the world. From the remarkable dynamic tensions of the compact body of the sculpture rise the figures of two athletes at the stirring moment of victory". The current FIFA World Cup(tm) Trophy cannot be won outright, as the regulations state that it shall remain FIFA's own possession. The World Cup(tm) winners retain it until the next tournament and are awarded a replica, gold-plated rather than solid gold. The new trophy is 36 cm high, made of solid 18-carat gold and weighs 6175 grammes. The base contains two layers of semi-precious malachite while the bottom side of the Trophy bears the engraved year and name of each FIFA World Cup(tm) winner since 1974. |

|

|

Jules Rimet Cup

Two years before the inaugural FIFA World Cup(tm) in 1930, the newly drafted regulations stipulated that the winners should be rewarded with a new trophy, with French sculptor Abel Lafleur being assigned this prestigious task.

The little trophy had a hazardous existence. The Italian Vice-President of FIFA, Dr.Ottorino Barassi, hid it in a shoe-box under his bed throughout the Second World War and thus saved it from falling into the hands of occupying troops.

Then in 1966, the cup disappeared while on display as part of the build-up to the World Cup in England and was only recovered, buried under a tree, by a little dog called Pickles. Finally, in 1983, it was stolen again, this time in Rio de Janeiro, and apparently melted down by the thieves.

The Brazilian Football Association, who had earned the right to keep the trophy after having won it three times, ordered a replica to be made. The original trophy was 35cm high and weighed approximately 3.8 kg. The statuette was made of sterling silver and gold plated, with a blue base made of semi-precious stone (lapis lazuli).

There was a gold plate on each of the four sides of the base, on which were engraved the name of the trophy as well as the names of the nine winners between 1930 and 1970.

Watch out!!! World Cup can be bad for your health

|

|

From Mogadishu to Kabul to Baghdad, watching the World Cup is proving to be bad for your health.

Sometimes it's fatal.

Hardline Islamic courts in the Somali capital have banned people from watching the action in Germany on television believing it to be against Muslim teaching.

In a brief but violent protest, two people were killed as gunmen, reportedly allied to the Joint Islamic Courts, forced three cinema halls to shut and warned football lovers against watching the matches which were being relayed through satellite.

"The Islamic courts have ordered the closure of three cinema halls," said Sukahola resident Abdulaziz Hanad.

"They want to make sure that nobody in Mogadishu watches the World Cup."

In war-torn Baghdad, many Iraqis feared they would miss out on the spectacle as the country's public broadcaster had no retransmission rights and the cost of subscriptions are beyond the means of many.

"I can't buy a decoder for the Arab channel that is showing all the matches," said student Mustafa Abdel Sattar.

For 175 dollars (135 euros), subscribers receive a special package that includes all 64 matches broadcast by the ART channel.

|

|

In Afghanistan, the 10,000-strong NATO force can watch the games on cinema-style screens at the International Security Assistance Force headquarters (ISAF) in Kabul.

German soldiers were the first to test-run the facility by watching their team's 4-2 win over Costa Rica on Friday 5,000 kilometres (3,000 miles) from where the match was being played in Munich.

They were some of the 200 NATO soldiers -- German, French, British, Macedonian, Turkish and Swiss -- who gathered in the Wolves' Den bar in Camp Warehouse to watch a live transmission of the match.

It's a scenario which would have been impossible five years ago when the Taliban banned television and initially outlawed football.

They relented, but insisted that players wore trousers and sleeves and ordered them to stop for prayers during matches.

Supporters were forbidden to cheer.

|

|

On Indonesia's Java island, where 5,800 people died in May's earthquake, locals were also trying to get access to World Cup television coverage.

Football fan Faturohman said the prospect of missing out on the tournament would be painful.

"I'm ruined. The electricity in this area is only enough for lights. We can't watch TV and besides that, my set was flattened by rubble from my house," said the 19-year-old whose favourite player is England striker Michael Owen.

"People in this area really love to watch soccer. Watching the World Cup would be entertainment for us while we are still grieving from the earthquake."

Elsewhere, there are other dangers.

Three Kenyans, hoisting a television antenna to watch the World Cup, were electrocuted and nearly killed when they accidentally hit a high-voltage power line in Nairobi.

Perfect tens grace the World Cup

In the slipstream of Puskas, Pele, Maradona, Zico, and Platini come Zidane and Ronaldinho, the heirs to all those who've worn the magical number 10 shirt with varying degrees of success at the World Cup.

Zidane and Ronaldinho are already World Cup winners. Pele and Maradona too.

Sadly Puskas, Zico and Platini never saw their dreams realised.

The man with the 10 on his back was once just an ordinary inside-left.

Now he's the player who waves a magic wand and weaves soccer spells and Ronaldinho, below par at this World Cup, recognises the pressure.

"I've always dreamt of following in the footsteps of the legends, the great players," said the Brazilian.

"Wearing the number 10 is very special since most of my idols also had that number."

Over 50 years ago, Ferenc Puskas, the first superstar number 10, was the heart and soul of Hungary, winning an Olympic gold medal before going on to rack up an international career of 85 caps and 84 goals.

At the 1954 World Cup, Puskas led favourites Hungary to the finals.

Despite defeating West Germany 8-3 in a group match, Puskas's Hungary lost 3-2 in the final to the same German team after taking a two goal lead.

His legacy passed to Pele who carried the number 10 in three World Cup winning teams in 1958, 1962 and 1970.

Pele is aware of the significance of the jersey and his reputation.

"People said to me it's just like Da Vinci or Michelangelo, you are going to leave something for the next generations," said Pele after opening a World Cup exhibition here.

The number 10 shirt he wore when he scored two goals as a 17-year-old in the 1958 final against Sweden was sold at auction for 105,600 dollars.

Four years ago, the number 10 shirt he wore in the 1970 final fetched 283,000 dollars.

Number 10s have even inspired a new book, The Perfect Ten.

"They are an exotic species, rendered more precious through the constant suggestion that they may be endangered by the game's steady evolution," writes author Richard Williams.

He quotes Socrates, part of Brazil's 1982 and 1986 World Cup teams, who believe they are a declining breed.

"A football player of the 1970s ran an average distance in each game of four kilometres. Today this has almost tripled, which means that the spaces between the players are relatively smaller," says Socrates.

"This causes a lot more physical contact, and makes it a lot more difficult for the player to create moves. Today, if you can't play with one touch, you have little chance of playing at the top level. Football has become uglier."

In that sense, perhaps it's not surprising that Argentina once wanted to retire the number 10 shirt in honour of 1986 World Cup-winning captain Diego Maradona.

The shirt was the property of an out-and-out forward when Argentina won the 1978 World Cup with Mario Kempes before he passed it to Maradona in 1982.

"Argentina has always produced very good players, and mine is just another name on the list. Diego was the greatest," said Kempes modestly.

French libero Platini inspired his nation to the 1984 European championship, but whether that made up for the heartbreak of losing in the 1982 World Cup semi-finals is questionable, where they lost a controversial tie to West Germany.

"That night I went through a scaled down version of a lifetime's worth of emotions," said Platini dramatically.

Number 10s like to be lyrical even when they are not playing.

Italy's Roberto Baggio, whose skyward penalty kick handed Brazil the 1994 World Cup, has never doubted his ability.

"With soccer I have the ability to do things differently," said Baggio.

"That is why I admire Leonardo da Vinci. He was able to create things other people wouldn't believe in."

World Cup losses undermine stock markets: study

Defeats in football World Cup games, depressing enough for teams concerned, also weigh heavily on the stock markets in their home countries, a study to be published this month, shows.

According to the study, to be carried in the Journal of Finance on June 29, a World Cup loss during a competition's group phase saves an average 0.38 per-cent off a team's home stock market index.

But during the knock-out phase of tournaments, markets fall by 0.49 per-cent, wiping billions off the value of investors' portfolios.

"To put the results in perspective, 40 basis points (0.40 per-cent) of the UK market capitalization as of November 2005 is 11.5 billion dollars. This is approximately three times the total market value of all the soccer clubs belonging to the English Premier League," the authors of the study said.

It was conducted by American professors Alex Edmans of MIT and Diego Garcia of Dartmouth College, as well as Norwegian Oeyvind Norli of Oslo's business school.

They compared stock market indices of 39 footballing nations in the wake of World Cup and other major international matches between January 1973 and December 2004.

"We already know that the markets' supposed rationality is in fact influenced by the feelings of individuals, and we worked on the basis that the feelings which universally affect the mood of investors are related to sport, especially to football," Norli told AFP.

While losses invariably affect stock market levels, victories don't necessarily cause a bull run, the study found, offering two explanations.

"Firstly, during a typical World Cup match victory simply takes you to the next stage while a defeat means you're out. There is more downside in defeat than there is upside in victory," Norli said.

"Secondly, one has to take into account the psychology of fans, who tend to overestimate their team's chances of success. In 2002, more than 80 per-cent of England fans thought that England would beat Brazil (in the quarter finals), while bookmakers gave England just a slightly more than 40 per-cent chance," he said.

Brazil won that match 2-1 and went on to win the World Cup, beating Germany 2-0 in the final.

Previous studies showed that England's defeat at the hands of Argentina in a penalty shoot-out in 1998 caused a 25 per-cent increase in heart attacks in Britain, and that homicide rates fluctuate in US cities according to American football results.

There were 15 local radio stations accredited to cover the game and a

representative of each ran onto the field to interview the goalscorer.

There were 15 local radio stations accredited to cover the game and a

representative of each ran onto the field to interview the goalscorer.