|

observer |

|

|

|

|

|

OTHER LINKS |

|

|

|

Australia's Timor coup world missed out on

|

|

|

Since then Alkatiri has had a series of heated arguments, particularly with Australia's foreign minister Alexander Downer over the issue. After bitter negotiations, it was only in January this year that Alkatiri was able to get Canberra to agree reluctantly to a 90-10 share in East Timor's favour, of the proceeds from the Greater Sunrise field. That was after agreeing not to proceed for at least 40 years with East Timor's claim to the disputed sea under the UN Law of the Sea convention, by which time most of the oil and gas in the area will be exhausted.

In 2005 the Alkatiri government was reported to have entered into negotiations with Petro China to build oil refining facilities in East Timor, which would undermine Australian plans to build a refinery in the northern Australian city of Darwin to process all Timor Sea oil from both sides of the border.

Deal

Last month Forbes reported that East Timor has awarded five oil and gas exploration contracts to Italy's Eni SpA and India's Reliance Industries through an international tender process, for which Malaysia's Petronas also tendered.

Perhaps its no wonder that Malaysia was one of the first countries to offer troops to the Australian-led intervention force. The contracts, which will include a production sharing deal with East Timor government was to have been signed on June 20th, and President Xanana Gusmoa was to visit China this month to cement the Petro China agreement, both of which have been blocked by the military intervention.

The award-winning Indonesian human rights group Tapol observed in an article in their website this month, that the Australian media, using news from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade in Canberra, has offered a "particularly distorted view of the crisis". Such misrepresentations are endlessly repeated until they become "truth" in the public conscience. "The prism through which the events in Timor-Leste are presented is that of the failed state'. These words are meant to ring alarm bells and Australian Defence Minister, Brendan Nelson wasted no time in pointing out that failed state equals terrorism" noted Tapol, which in an analysis of the Australian media reporting found that in contrast to the wily Marxist terrorist are his political rivals, who are Canberra's favourites - the "universally loved and admired" President Xanana Gusmao, the "ever-obliging" Nobel laureate Foreign Minister Jose Ramos-Horta and the "popular" Australian troops who have arrived to save the country, though they have been criticised for being notably passive about the arson and looting in sectarian attacks.

The rebel leader Major Alfredo Reinado (loyal to Xanana Gusmao, grateful to Australian troops, lover of Australian VB beer and enemy of Alkatiri) is described in surprisingly neutral terms: he is merely "swaggering" and "Australian-trained".

Gas reserves

It is his tough stance on negotiating East Timor's rights to its oil and gas reserves with Australia over the past 5 years which has earned Alkatiri the wrath of the Australian government which has tried to bully its poor neighbour into submitting to Canberra's ambitions to control exploration and exploitation of these natural resources.

While Australia dragged its negotiations, they took almost A$ 2 billion in royalties from the disputed oil fields in the Timor seas since 1999, while giving back approximately A$ 400 million in aid over the same period, thus making them dependent on Australian aid.

Alkatiri has been trying to build an economy not dependent on foreign aid.

He has refused to take conditional aid from the World Bank, and also spoken out against privatisation of electricity and managed to set up a "single desk" pharmaceutical store, despite opposition from the World Bank.

He has invited Cuban doctors to serve in rural health centres and help in setting up a new medical school, abolished primary school fees and introduced a free mid-day meal for children, and made religious instructions voluntary in schools.

All these, and fact he was educated and spent 24 years in exile in Marxist Mozambique, have been cited by the Australian media as hallmarks of a communist leader.

In contrast, the rebel leader Reinado, a former exile in Australia is believed to have been trained at the national defence academy in Canberra, and Australia's preferred candidate for the prime ministership foreign minister Ramos Horta set up a diplomatic training programme at the University of NSW in Sydney during his years of exile in Australia.

Canberra plot

On 7 May, Mari Alkatiri called the recent unrest a 'coup' - saying that 'foreigners were coming to control and divide East Timor again' with 'foreign advisors meeting with politicians and going to the hills' to meet rebels.

Rob Wesley-Smith, spokesperson for a Free East Timor believes that Alkatiri has dictatorial tendencies and Fretilin has become corrupted, but, he blames the Howard for precipitating the crisis by withholding since 1999, A$ 2 billion of oil revenue due to East Timor.

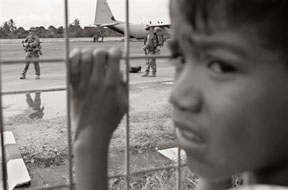

He said in an email interview that images shown on television after Australian troops arrived in Dili where they stood by watching as looting and burning went on made him wonder, if it was a part of a sinister plot by Canberra to declare East Timor a failed state "so that they could control the Timor Sea (oil) theft".