|

observer |

|

|

|

|

|

OTHER LINKS |

|

|

|

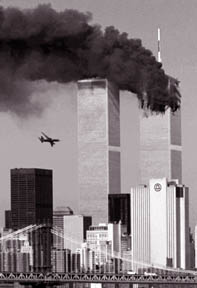

Lankan tsunami or WTC, people tend to live, or die, togetherHow the disaster starts does not matter: It could be a plane crashing into the World Trade Center, it could be the sea receding rapidly ahead of an advancing tsunami, it could be smoke billowing through a nightclub. Human beings in New York, Sri Lanka and Rhode Island all do the same thing in such situations. They turn to each other. They talk. They hang around, trying to arrive at a shared understanding of what is happening. When we look back on such events with the benefit of hindsight, this apparent inactivity can be horrifying.

“What the sea is doing is not marvelous,” we want to tell those fishermen in Sri Lanka, as they gather together to discuss the amazing phenomenon of the receding waters. “You only have a few minutes to get to higher ground before the tsunami arrives.” “Please,” we pray, as we watch video of patrons at a Rhode Island nightclub in 2003 putting their heads together to figure out whether the pyrotechnic display on stage is just very dramatic or a stunt that is out of control. “In 60 seconds, it will be too late.” Experts who study disasters are slowly coming to realize that rather than try to change human behavior to adapt to building codes and workplace rules, it may be necessary to adapt technology and rules to human behavior: In the narrow window between the siren of disaster and disaster itself, people always want to understand what is happening. You can see this yourself the next time the fire alarm goes off at work, school or home. People will look at one another. They will ask each other: “Is it a drill? Shall we give it 30 seconds to see if it shuts off on its own? Can I just finish sending this e-mail?” For all the disaster preparations put in place since the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the behaviour of people confronted with ambiguous new information remains one of the most serious challenges for disaster planners. Computer models assume that people will flow out of a building like water, emptying through every possible exit. The reality is far different. People talk. They confer. They go back to their desk. They try to exit the building the way they came in, rather than through the nearest door. Building engineers at the World Trade Center had estimated that escaping people would move at a rate of more than three feet per second. On Sept. 11, 2001, said Jason Averill, an engineer at the National Institute for Standards and Technology who studies human behavior during evacuations, people escaped at one-fifth that speed. Although the towers were only one-third to one-half full, the stairwells were at capacity, he said. Had the buildings been full, Averill said, about 14,000 people would probably have died.

That is because the larger the group, the greater the effort and time needed to build a common understanding of the event and a consensus about a course of action, said sociologist Benigno Aguirre of the University of Delaware. If a single person in a group does not want to take an alarm seriously, he or she can impede the escape of the entire group. The picture of what happened on Sept. 11 is very different from conventional assumptions about crowd behaviour, in which it is assumed that people would push each other out of the way to save their own lives. In actuality, human beings in crisis behave more nobly - and this could also be their undoing. People reach out not only to build a shared understanding of the event but also to help one another. In so doing, they may delay their own escape. This may be why groups often perish or survive together - people are unwilling to escape if someone they know and care about is left behind. Contrary to the notion of selfish behaviour in crises, Aguirre said, the accounts of how people fled the World Trade Center building on Sept. 11 reveal only one instance of a man who heard an explosion, laced up his tennis shoes and ran until he was far away from the building. This may be why in fire disasters, Aguirre said, entire families often perish. “The most important factor for human beings is our affinitive behaviour,” said Aguirre. “You love your child and wife and parents; that is what makes you human. In conditions of great danger, many people continue to do that. ... People will go back into the fire to try to rescue loved ones.” - The Washington Post |

“Get out now!” we want to scream at those people in the upper stories

of the South Tower of the World Trade Center, as they huddle around

trying to understand what caused an explosion in the North Tower at 8:46

on a Tuesday morning in September. “You only have 16 minutes before your

exit will be cut off,” we want to tell them. “Don’t try to understand

what is happening. Just go.”

“Get out now!” we want to scream at those people in the upper stories

of the South Tower of the World Trade Center, as they huddle around

trying to understand what caused an explosion in the North Tower at 8:46

on a Tuesday morning in September. “You only have 16 minutes before your

exit will be cut off,” we want to tell them. “Don’t try to understand

what is happening. Just go.”  One study after the 1993 attack on the World Trade Center found that

group size was a significant factor in determining how quickly people

exited the building after a van loaded with explosives went off in an

underground parking lot: Individuals who were part of larger groups,

such as large workplaces, took longer to escape than individuals who

were part of smaller groups.

One study after the 1993 attack on the World Trade Center found that

group size was a significant factor in determining how quickly people

exited the building after a van loaded with explosives went off in an

underground parking lot: Individuals who were part of larger groups,

such as large workplaces, took longer to escape than individuals who

were part of smaller groups.