|

observer |

|

|

|

|

|

OTHER LINKS |

|

|

|

Tsunami-tossed city's survivors struggle to carry on"This is it," said Safrial, a carpenter, to his two young sons when a towering tsunami of black water rushed toward them two years ago. "This is the end of the world."

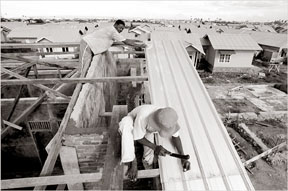

For most people who lived around him it was, and today Mr. Safrial, 45, who uses only one name, hammers and sweats in the sun in a neighbourhood where he knows the names of more of the dead than of the living. He hammers constantly, even as he talks. "This was a test from God," he said. "For those who died, it was disaster. But for the survivors, we must pass the test and become better people in every way." Not everybody has met the challenge, he said. Across Aceh Province, where the tsunami on Dec. 26, 2004, hit the hardest, the process of recovery has been a mixture of progress and disappointment. All across the ravaged cityscape, scraped bare by the waves, thousands of tiny, toy-box houses have sprung up in recent months as a program of rebuilding gains momentum. But many of the new houses are empty because they lack water, sanitation and electricity and because there are no schools, clinics or commercial activity nearby. Many of the people whose homes they replaced were swept away to their deaths. Old landmarks are gone, and it is bewildering to trace a remembered path through this sketch of a city. At night the heart of the ruined area is almost as dark and silent as it was before construction started. This rebuilt city of ghosts seems like a ghost town. The tsunami, caused by an earthquake off the shore of Aceh, took 230,000 lives and left nearly two million people homeless in more than a dozen nations - large numbers in India, Sri Lanka and Thailand as well as here in Indonesia. One of the worst natural disasters in modern history, it stirred an unparalleled outpouring of billions of dollars of aid. On a stub of a ruin amid the new houses here, a fading spray-painted message reads: "Sunday 26 December 2004 in the morning: the world is crying for Aceh." But by some estimates only one-third of the promised aid has been distributed to affected countries, and much of that has been lost to corruption, mismanagement, political squabbles and bureaucratic dead ends.

Hundreds of thousands of people still have no permanent homes or jobs, and it seems that many will live out their lives as refugees of the tsunami. Temporary sheltersIn India, the British aid group Oxfam estimates that 70 percent of affected people still live in temporary shelters. In Sri Lanka the revival of a civil war has made life even more precarious for survivors. The beaches of Phuket in southern Thailand seem to be an exception, with life and tourism thriving again, though the scars of trauma remain. The last 451 unidentified bodies, of more than 5,000 who died, are being buried and their DNA is being kept on file. Many of the problems of reconstruction are playing out here in Aceh, where 170,000 people died and more than half a million lost their homes. Hundreds of small earthquakes, as well as floods and landslides, have added to the misery since then. In recent days at least 70 people have been killed in the area by flash floods. "We are constantly overwhelmed by the massive task confronting us," said the director of the Indonesian government's reconstruction agency, Kuntoro Mangkusubroto, at a conference of donors in New York in November. One of the poorest provinces in Indonesia, Aceh cannot easily absorb the $7.1 billion in international aid that has been pledged, Mr. Kuntoro said, and does not have the capacity to carry out the quantity of rebuilding that is needed. Some projects have been put off, he told reporters here, because the province has only nine asphalt plants and cannot meet the demand. JoblessnessAlthough joblessness is a critical problem for the people here, most construction workers come from outside the affected area, because there are not enough skilled workers here, said Ian Small, Oxfam's senior program manager for Aceh. But Mr. Kuntoro said many of the problems had been brought on by the people responsible for reconstruction. Coordination among hundreds of aid groups is "the challenge of challenges," he said in New York, as projects conflict or overlap. "Corruption is endemic. We cannot let down our guard for a moment." Donors have been diverted by "childish games" of internal politics, he added. He said 57,000 houses had been built, about half the needed number estimated by Oxfam. But he said 100,000 people remained in temporary barracks. Here and there among the new pink and rust-coloured houses are the tile floors, carpeted by creepers, that are all that remains of many of the buildings that were swept away. Azahara Amin, 41, a jobless office worker, pointed to patches of weeds that were once the homes of his neighbours. "This is a house, and this is a house over there," he said. "These were four more houses here. They all belonged to my relatives; most of them are dead. Only four houses have been rebuilt." With most documents lost to the tsunami, it is often impossible to confirm ownership. If an owner has died, an heir must be found, and once a house is built there may be no one to occupy it. Mr. Kuntoro said that 140,000 properties had been surveyed but that only 7,000 deeds had been handed out, because complex regulations had not yet been drawn up. An additional 25,000 families have no chance for resettlement because they did not own land or because their land was permanently inundated, Oxfam said. Despite the problems, a new kind of normalcy has emerged here as life shifts from tents to barracks to houses and people try to patch together the gaps left in their lives by the tsunami. The world did not end two years ago for Mr. Safrial, the carpenter, who ran with his sons to safety at the Grand Mosque several blocks away. But Nur Aini, a college teacher whose house he was repairing the other day, must live with the loss of her 18-year-old daughter, who was torn from their home by the waves. "She was just about to graduate and was going to become a doctor," Ms. Aini said with a quiet smile. "But that was not her fate, and we have to accept it. She's gone, but we continue." NYTIMES |