|

Making a bigger world - physically, intellectually and morally

By Carl Muller

As I mentioned in one of my previous articles we can now deal with

the Renaissance - a century of expansion - from 1500 to 1600. Three

essentials brought this about: the new age of discovery, the Renaissance

and the Reformation. As you know, Renaissance stood for the Revival of

Learning, and that made a good beginning in the reign of Henry VII in

the 15th century.

Then came Henry VIII, Edward VI and Mary in the 16th century, and

from 1509 to 1559 arose the war of English religious independence. It

was under Elizabeth, however, that the period of literary achievement

took off, unequalled in the annals of man.

We had the 15th century Greek scholars who fled to Italy when the

Turks captured Constantinople. In Italy, these scholars became tutors,

telling of and teaching the literary masterpieces of Greece that Europe

seemed to have forgotten for a thousand years.

Suddenly, the “Iliad” and the “Odyssey”, the works of Aeschylus,

Sophocles, Euripides, Pindar, Theocritus, Herodotus, Thucydides, Plato

and Xenophon were “rediscovered” and it launched the Renaissance - also

known as the “New Birth” in Italy.

From there it spread to become the mark of every well-educated person

to read, write and speak Latin and also know Greek. What is more, the

scholars also brought to Italy the Greek Testament, and that started off

the translation of the Scriptures, becoming a powerful aid to the

Reformation. All the old medieval forms of university education came

apart.

Who pioneered the Renaissance in England? Among many others, there

was Thomas More - and they all wrote in Latin. John Colet founded St.

Paul’s School.

Thomas Linacre wrote a Latin Grammar that is still referred to as the

“Eton Latin Grammar” and Sir Thomas More wrote a Latin book on sociology

that is among the world’s classics. He modelled it on Plato’s “Republic”

and told of an ideal state that was given the name “Utopia” - meaning

“No Place”.

It was the great Dutch scholar Erasmus, who was teacher and leader of

these pioneers who began to call themselves “humanists”. Erasmus, you

must remember lived for several years in England. By 1520, almost 90

percent of all the books sold in Oxford were written by Erasmus and they

included a religious treatise, “Enrichiridion” in the 1540s and a Latin

book for beginners, “Colloquia” in 1546

So what did we have? All of cultured England was turning to Italy,

and I want to tell you of two men who gave to us the birth of the

English sonnet and blank verse. Sir Thomas Wyatt discovered the sonnets

of Petrach and introduced their form into English literature.

The sonnets were poems of 14 lines of iambic pentameter, divided into

two parts of eight and six. Wyatt also introduced a personal note,

something that had never been previously considered in English poetry.

Together with Wyatt, there was Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, who also

made an important contribution by writing blank verse in iambic

pentameter. It was this measure in which, later, Shakespeare’s plays,

Milton’s “Paradise Lost”, Wordsworth’s “Excursion” and Tennyson’s

“Idylls of the King” were also written.

Surrey (as he is called) translated Virgil. He was a soldier, was

once arrested for eating meat during Lent and for using his crossbow to

break windows.

Henry VIII had him beheaded because he feared that Surrey might wish

to seize the throne, but it goes deeper than this for, as we know, Henry

VIII married Surrey’s cousin, Catherine Howard.

The joint work of Wyatt and Surrey was an inspiration. Other great

poets followed, and there were so many that the England of queen

Elizabeth was said to be “a nest of singing birds.”

We will run through this new wave of literature next.

Beyond the greener pastures

By Don Dayapala Wijewardana

[email protected]

When the phone rang at 2 am I knew it was either a cranky insomniac

pressing random numbers on his phone or some urgent news from home. Half

asleep, I grabbed the phone. It was my sister Nita from London. “Is that

you Neal? I just had a call from Uncle Walter in Sri Lanka. I have bad

news”, Nita burst out with her voice breaking.

I realised then this may be the dreaded telephone call I hoped I

would never receive. “Is it mum?”, I asked with my hands trembling. I

knew she was admitted to hospital earlier that week. Without answering

Nita burst out sobbing. The next ten minutes, perhaps more, we spent

without many words but each one taking the blame for leaving Sri Lanka

allowing mum and dad to spend their sunset years helplessly alone.

Nita left for London with her husband many years ago. She was able to

do so without a sense of guilt leaving the parents as I was still there.

But several years later when I was offered a position in New Zealand I

was faced with a dilemma.

In every respect it was a great opportunity. And as my wife Tania

took pains to explain, it was even more important for the sake of our

children. I didn’t need any convincing: but I did not have the heart to

leave my parents.

Eventually it was my mother who persuaded us to go. “We are alright

here Neal. We have very good neighbours and we have enough means for a

comfortable living. You have the whole life ahead of you and need to

think of the future of these children”, and she noted somewhat

cheerfully, “We can keep in touch regularly over the phone and could

even visit you sometime”.

“Who knows, if the place is good, perhaps mum and I could come over

to live there”, dad added. I knew that whether they meant these or not,

they did not want to stand in the way if we wanted to leave. With that I

could no longer muster any more counter arguments against Tania’s.

It is now almost ten years since we moved to New Zealand. In that

time mum and dad have visited us twice. But the house we bought with a

separate unit meant for them did not lure my dad to live up to his

world. In a way I did understand them.

Plucking them away from their familiar environment and their friends

could have shattered their lives. I thought it was cruel to push them to

stay with us like birds in a cage. But often we do not see beyond the

greener pastures when lured by the opportunity to live more comfortably.

Now I feel I have paid the price for abandoning them. Some say that

parents in developing countries have children as an insurance against

old age. I wasn’t so sure of the idea but now I think we had reneged on

my parent’s insurance cover.

Both our families were in Sri Lanka for the funeral. After about a

week Nita went back to London. Tania too left shortly after, as our

elder children could not afford to miss school for long. But I did not

join them which would have meant leaving dad alone.

At the same time I knew I could not stay away too long from my job

and my family or persuade dad to come with us knowing his past

reluctance. Perhaps out of guilt, but more due to lack of a solution, I

decided to stay back a bit longer along with our three year old son,

Sahan.

It is now more than two months since mum’s funeral. In that time dad

has hardly talked to anyone. He sits all day in his usual chair in the

lounge looking out of the window rolling his thumbs in a rhythm painful

to watch.

Sometimes tears roll down his cheeks. He wipes them with his palms. I

look the other way not to embarrass him. I see how much his body has

deteriorated during these two months. He looks tired and hunched. I

invited uncles, aunts, neighbours and even the monk from the temple to

talk to him but none of it made any difference.

“We all feel just like you dad. But this is her karma. It is a

natural process. Each one of us has to take that route one day. But in

the

meantime life has to go on. You need to pull yourself together”, I

berated him once in desperation. But immediately after I regretted it.

After all it was his wife and companion that he lost. Although it was my

mother too I lived thousands of miles away. Anyway all that was to no

avail.

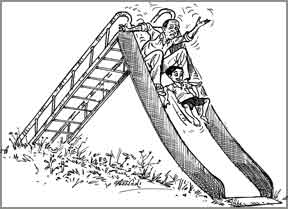

With a lot of persuasion I got dad to come along with us to a nearby

playground which had become a favourite place for Sahan. There Sahan was

able to ride on the swing, jump on the trampoline and slip down the

slide. He loved every minute of it. But his favourite was the flying

fox.

A big sign in red says it was for children over ten. At his

persistence I lifted the tiny bundle on to it at the top end and give a

slight nudge which carries him all the way to the other end. I run down

following him to catch him half way when he returns from the rebound.

I noticed dad quietly watching all the manoeuvres of Sahan without

any comment or involvement. And when we returned home it was straight to

the same seat and the same routine.

Our walk to the playground has now become a daily routine. That was

the only way I could keep Sahan happy. Dad also joins us often without

much persuasion. Sahan sometimes walks with dad holding his hand talking

incessantly and bombarding him with questions.

Dad hardly responds to them but that does not deter Sahan. One day I

was busy and Sahan went to the playground with dad ahead of me. When I

arrived around half an hour later I found Sahan on top of the slide

urging granddad also to join him. I saw him initially reluctant but

Sahan

kept egging him on. “Come on Seeya you can do it”, he was urging

granddad using the only Sinhalese word he knew. Watching from a distance

I saw dad slowly walking up to the ladder, grab hold of the top rung and

gradually lifting his frail body up to the first tread. I was horrified

what would happen if this 75 year old fell, but decided not to

intervene. Sahan kept on encouraging him all the time as if dad was a

younger sibling. “Be careful Seeya. Hold on tight. If not you will

fall”.

After another five minutes or so dad lifted the other foot and

climbed to the second rung of the ladder. From the grimace on his face

it was clear arthritis was making the climb very painful. But he kept

on, with long rests in between. All the time Sahan was guiding and

praising him.

After about half an hour (it seemed much longer to me) he cleared the

last step and climbed on to the top of the slide. Now there was only one

way for both of them to come down - sliding down. I was even more

worried about what could happen. Sahan was giving more instructions.

“Now I will go first and you come immediately behind me Seeya. If it

gets too fast push your feet onto the sides and that will slow you down.

Be very careful”.

I rushed to the bottom end of the slide agonising over what was going

to happen. It took some time for Sahan to persuade dad but eventually

the two were ready for the plunge. Sahan came down first. He did not

attempt to slow down and virtually crashed on to me standing at the end.

Dad followed with some delay, almost tumbling but reached the bottom

safely. For the first time since mum died he was laughing along the way.

“Seeya, did you also go on the slide when you were little?”, I heard

Sahan asking that evening at home. Dad laughed and laughed. This was the

second time for the day he laughed.

“During our time there were no slides like this, darling”, he

replied. “The closest to a slide we had was to sit on a branch from a

coconut tree and slide down hill slopes. It was very exciting and often

we ended up with many scratches on the body” and they both laughed

together.

I was amazed at how a three-year old accomplished something that

adults have been trying unsuccessfully for months. During the days that

followed dad and Sahan spent a lot of time together. They went for

walks, worked in the garden and in the evenings, dad read stories to

Sahan. Dad now hardly sat in his usual chair watching the road or

rolling his thumbs.

All this time Tania kept on telephoning from New Zealand, almost on a

daily basis, asking when we were coming home. My boss had been enquiring

about me and I knew he was expecting me back at work. Sahan used the

telephone opportunity to brag about his daily escapades to his mum and

siblings.

I kept on assuring her it would not be long before we returned. But

how long? I did not know. I was truly between a rock and a hard place.

One evening it was dad who brought up the question of our return. “I

love having you guys around but how can you stay here like this? You

need to get back home.”

I was pleased that he was alive to what was going on. “I know dad we

have to get back. But .....” I did not know how to complete the

sentence. “Yes I know. Perhaps I could come with you and be with Sahan

when you two go to work. I could take him to the playground too”.

Then only I realised the closeness of the bond that had developed

between Sahan and dad.

Sahan captured my own sentiments when he responded to the suggestion:

“It’s cool dad if seeya can come with us.”

Amrita Pritam - Ethical, didactic and romantic

Amrita Pritam was born in 1919 in Gujranwala, Punjab, now in

Pakistan. She was the only child of a school teacher and a poet.

Amrita’s mother died when she was eleven. Soon after, she and her father

moved to Lahore.

Confronting adult responsibilities, she started writing poetry in her

teens under the influence of her father and became the proud author of a

collection of poems, Amrit Lehran in 1936.

Such was the grip of the muse in her soul that she churned out half a

dozen collections of poems in as many years between 1936 and 1943.

Amrita Pritam is an eminent Punajbi poet and a prolific writer. She has

written twenty four novels, fifteen collections of short stories and

twenty three volumes of prose.

She is considered the first prominent female Punjabi writer and poet.

When the former British India was partitioned into the independent

states of India and Pakistan, she migrated to India in 1947.

Amrita was not a highly educated woman, not exposed to good writing

in languages other than Punjabi, nor sophisticated enough to add new

dimensions to her own. She was besotted by Bollywood and believed

getting one of her novels or short stories accepted by a film-maker was

the ultimate success.

All her stories and novels were sob stuff and uniformly second rate.

Her first collection was published when she was only sixteen years old,

the year she married Pritam Singh, an editor to whom she was engaged in

early childhood, but it was not successful.

After her divorce in 1960, her work became more clearly feminist.

Many of her stories and poems drew on the unhappy experience of her

marriage. Amrita Pritam was at her best in Sunehe (Messages) published

in 1955 in which she mixes the romantic and the sentimental within with

the progressive callings outside.

A number of her works have been translated into English, French, and

Japanese and other languages from Punjabi and Urdu ,including her

autobiographical works Black Rose and Revenue Stamp (Raseedi Tikkat in

Punjabi).

The tone of her poetry was ethical, didactic and romantic, clouded in

platonic overtones, with a degree of elasticity in form and diction.

Her works have been defined as a ‘woman’s lyric cry against

existential fate and societal abuse’, and have been widely translated.

She was conferred the D.Litt. degree by five universities. She is the

first woman recipient of the Sahitya Akademi Award and was honoured with

Padma Shree in 1969.

Two of her novels have been made into films. She received the

Vaptarow Award and the Bhartiya Jnanpith Award. She was the voice of

Punjabis all over the world.

Amrita Pritam lived the last forty years of her life with the

renowned artist, Imroz. She died on 31st October 2005 at the age of 86,

after a long illness, survived by her daughter, Kundala; her son, Navraj;

and her grandson, Aman.

Compiled by Ishara Mudugamuwa

[email protected] |