|

Man preys on man:

A closer look at “The Village in the Jungle”

by Amal HEWAVISSENTI

|

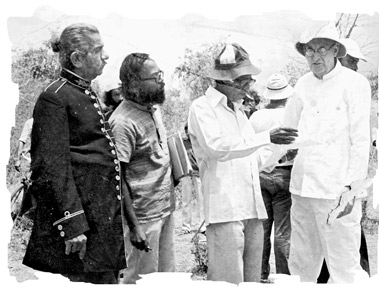

Scenes from the film “The Village in the Jungle”

|

The novel, “The Village in the Jungle” by Leonard Woolf is set in a

remote village in the southern part of Sri Lanka at the outset of

twentieth century. The novel is indeed a full-frontal dissection of

suffering and hardships of rural people being harassed by their fellow

men and nature. Though the Englishmen in London greeted his work with a

certain amount of appreciation, it was widely recognised in Sri Lanka as

the first ever realistic display of lifestyle of the downtrodden rural

people and tragedies that surround them. Woolf’s position in the Civil

Service (1904) gave him golden chances to explore the pathetic

dimensions of people and study the values and beliefs that had shaped

them. His short spell of stay in the country brought him in contact with

the miserable condition of rural people who were being ruthlessly

exploited by the local agents of western imperialism. Woolf’s is a

purely sardonic attitude to western imperialism and its local

representatives who are blindly executing “law” against “offenders.” In

short, the novel vividly mirrors the writer’s dissatisfaction with the

colonial system and it’s failure to grasp the needs and moods of rural

people. Here, Woolf’s tone carries a strong current of malice against

the inability of the existing imperial law to do justice for the

suffering people. The novel, “The Village in the Jungle” by Leonard Woolf is set in a

remote village in the southern part of Sri Lanka at the outset of

twentieth century. The novel is indeed a full-frontal dissection of

suffering and hardships of rural people being harassed by their fellow

men and nature. Though the Englishmen in London greeted his work with a

certain amount of appreciation, it was widely recognised in Sri Lanka as

the first ever realistic display of lifestyle of the downtrodden rural

people and tragedies that surround them. Woolf’s position in the Civil

Service (1904) gave him golden chances to explore the pathetic

dimensions of people and study the values and beliefs that had shaped

them. His short spell of stay in the country brought him in contact with

the miserable condition of rural people who were being ruthlessly

exploited by the local agents of western imperialism. Woolf’s is a

purely sardonic attitude to western imperialism and its local

representatives who are blindly executing “law” against “offenders.” In

short, the novel vividly mirrors the writer’s dissatisfaction with the

colonial system and it’s failure to grasp the needs and moods of rural

people. Here, Woolf’s tone carries a strong current of malice against

the inability of the existing imperial law to do justice for the

suffering people.

Apart from that the novelist’s treatment of people of the rural

society is both sympathetic and empathetic. He does not have the

narrowness in mental outlook in describing the people of Beddegama in

contrast to Robert Knox who was markedly prejudicial against Sinhala

people.

Bitter truth of jungle

The plot and action of the novel unfold against the background of

vast stretch of jungle which is the ground of struggle for survival. The

reader is left with the task of puzzling out the layers of meaning in

what the novelist says about the jungle ready at any moment, to intrude

on the village. “All jungles are evil, but no jungle is more evil than

that which lay about the village of Beddegama.” This strikes the keynote

of the “rule of jungle which is first fear and then hunger.” At the same

time, the novelist has a broadly focused view of the people in the

village.

“In their faces you can see plainly the fear and hardship of their

lives. They are very near to the animals which live in the jungle around

them. They look at you with the melancholy and patient stupidity of the

buffalo in their eyes or the cunning of the jackal.” It is blatantly

obvious to the writer that rural life is well beset with hardship and

suffering despite many fairy tales of their comfortable life in a

healthful surroundings.

Silindu’s family

Silindu and his two daughters invariably rise to a heroic stature in

their lamentable struggle for survival against corrupt villagers and

nature itself. The “tikak pissu” father, Hinnihami and Punchimenika are

humanely tied together by unbreakable instinctive bonds. Silindu’s

relationship with and understanding of animals give him the idea that

animals have the right to live just as humans do. Though this small

family is labelled as “social misfits” by villagers, the father and two

daughters are clearly personalised by strong affection for each other,

familial love and honest feeling for their home. Silindu goes beyond the

bounds of convention by feeding his daughters’ minds with a culture of

folk tales, Buddhist parables, legends and beliefs that enrich their

upbringing. Silindu’s behaviour and attitudes set him apart from the

rest of the villagers and his daughters, unlike the girls, were brought

up with an intimate knowledge of the jungle. The villagers call him

“Tikak Pissu” because of the way he squats on the compound looking at

the jungle and his eccentricities like talking to animals while walking

in the jungle. However, the morally bankrupt Babehami, Punchirala and

Fernando play shrewd diplomatic games on him and black mail him in

different ways. His intense love for Punchimenika is made clear when he

gets to know Babun’s decision to marry her and bursts out. Silindu and his two daughters invariably rise to a heroic stature in

their lamentable struggle for survival against corrupt villagers and

nature itself. The “tikak pissu” father, Hinnihami and Punchimenika are

humanely tied together by unbreakable instinctive bonds. Silindu’s

relationship with and understanding of animals give him the idea that

animals have the right to live just as humans do. Though this small

family is labelled as “social misfits” by villagers, the father and two

daughters are clearly personalised by strong affection for each other,

familial love and honest feeling for their home. Silindu goes beyond the

bounds of convention by feeding his daughters’ minds with a culture of

folk tales, Buddhist parables, legends and beliefs that enrich their

upbringing. Silindu’s behaviour and attitudes set him apart from the

rest of the villagers and his daughters, unlike the girls, were brought

up with an intimate knowledge of the jungle. The villagers call him

“Tikak Pissu” because of the way he squats on the compound looking at

the jungle and his eccentricities like talking to animals while walking

in the jungle. However, the morally bankrupt Babehami, Punchirala and

Fernando play shrewd diplomatic games on him and black mail him in

different ways. His intense love for Punchimenika is made clear when he

gets to know Babun’s decision to marry her and bursts out.

“The girl is too young. I cannot give her to you, or evil will come

of it.”

Babun’s romance

Babun, a dispassionate young man in Beddegama is a relative of the

village headman and is in wild love with Punchimenika after observing

her from his compound. To him, the marriage with Punchimenika means

nothing more than having children by her and having his meals prepared

by her. She is naturally attracted to him through a complex

psychological instinct of fear and desire. As a result, Babun is beset

by a bombardment of fierce abuse and criticism by Babehami (Headman) and

other villagers for choosing a girl from a “rejected” family in the

village opinion. Babun says “I like no other woman... she is unlike the

other women of this village... in whose mouths are always foul words...”

He is by no means a type of man who is ready to bend personal opinion or

principles to the interests of the morally bankrupt superpowers in the

village.

What runs parallel to this drama is Hinnihami being sacrificed to

Punchirala, an evil looking, malevolent dealer in charms. The repellent

Vedarala tactfully employs superstitions and beliefs held by villagers,

specially Silindu to make the rebellious girl give into his marriage

proposal. Woolf says, “She was broken; tired and numb with fear and

despair... like a wild animal against a trap, she had fought against the

idea of giving herself to Punchirala.” However, disdainful she is of

Punchirala at first, she is forced to agree to marry him when his evil

course of action brings Silindu on the threshold of death. However, she

identifies herself with most evilpower and lets loose a torrent of

outbursts, “Are you frightened Punchirala? The binder of yakkhas is

frightened of Yakini.” Being an emotional wreck, she desperately breaks

away from Punchirala but ultimately falls prey to the sheer inhumanity

if man and his superstitious beliefs. She is destroyed not by devils

that her father had spoken of, but by evil plots by man himself. This

assuredly is the tragedy of the novel. Even her “son”, the fawn on whom

she has been so much emotionally dependent, is ruthlessly destroyed by

man’s inhuman attitudes.

Failure of Imperial Law

With alluring display of the power of money and promised life of

luxury, Fernando, assisted by Babehami make slow but evil plans to

seduce Punchimenika. As she is persistent in her loyalty to Babun, they

bring Silindu and Babun to the “White Hamadoru” of the court of

Hambantota, under false charges. Ratemahathmaya, a typically strong

believer in power and authority granted by colonial law, shows little

sympathy for the bareforked animal (Silindu)” squatting on the floor of

the judge’s bungalow. When the “Judge Hamadoru” releases Silindu and

orders Babun to rigorous imprisonment, Silindu, for the first time

realises that he has been hunted. Throughout judge’s long drawn speech,

Silindu’s mind goes totally blank and finally they find him snoring and

fast asleep on the ground.

This is a powerful illustration of imperialism in which a judge gives

a verdict on a man with a language he does not understand. Woolf’s

penetration of working of the mind of such a desperate man is really

marvellous. “They call me a hunter, a Vedda? To be hunted for years and

not to know it! It is the headman who is the vedda, a very clever

hunter... I am a buffalo wounded... A wise hunter does not follow up the

wounded buffalo where the jungle is thick...” There are Silindu’s words.

Silindu painfully realises that the depravity of the headman and the

lustful Fernando are responsible for the chain of unfortunate events in

which his family was gradually destroyed. He kills Babehami and Fernando

and goes straight to Ratemahathmaya. However, the judge, though totally

powerless against the existing colonial law, has a better understanding

of people like Silindu and sees through the sheer injustice done to them

by the machinery of law and corrupt officials. Woolf voices his theme of

man’s inhumanity to man through judge’s honest, analytical discussion

with Ratemahathmaya to whom the case seems to be simple. The judge’s

final remark coming from his moral conscience goes far beyond the scope

of legal machinery in operation.

“Savages you mean. Well I don’t know. I rather doubt it. I expect

he’s a quiet sort of man. All he wanted was to be left alone, poor devil

Ratemahathmaya, you don’t know the jungle properly...” They won’t touch

you if you leave them alone...”

Finally the village has changed beyond recognition and gradually

disappears into the jungle as an unmistakable offshort of corrupt forces

at work. No foreigner has shown more insight into the deep recesses of

suffering of people in rural areas as Woolf in his immortal prose.

|