|

Interpreting Interpreters:

Strategies of Resistance in Afro-American poetry

By Mahendran THIRUVARANGAN

|

Lucille Clifton addresses a conference

|

African-American poetry has a political function in that not only

does it record the oppression of African-Americans in the USA by Whites

but it also represents and "re-presents" African-Americans' history,

culture and civilization, which are either erased completely from or

misrepresented and looked down upon in mainstream American poetry.

Although we could call African-American poetry a "literary rebellion"

against mainstream American poetry, which depicts the values and culture

of the White, middle and upper class, Christian, heterosexual, male

Americans as "American values" and "American culture," it should be

noted that not all African-American poets nor all the poems written by

an African-American poet are counter-hegemonic in spirit.

This essay, making special reference to six poems written by

African-American poets, examines why interpreters are (not) needed to

explain Afro-American poetry to readers outside the African-American

community. Although poets of both genders are given equal importance, I

am aware that my selection of poems is not representative of the entire

body of African-American poetry, for the poems examined here barely map

the internal differences found in the African-American community along

the lines of region, religion, class and ideology.

Langston Hughes' 'The Negro Speaks of Rivers' is a relatively less

challenging poem to non-African-American readers. The African-American

speaker in the poem, by describing his historical attachment to the

different rivers in Africa and North America, at the mouths of which the

ancient civilizations of the world emerged, asserts that

African-Americans' civilization is one of the founding civilizations of

the world:

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young,

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep,

I looked upon the Nile and raised Pyramids over it,

I heard the singing of the Mississippi […].

|

Gwendolyn Brook-34 |

Hughes, through the literary space of poetry, reclaims in this poem

the geographic spaces of civilization, which the "White custodians" of

European and American civilizations deny African-Americans. Being

counter-hegemonic in spirit, the poem challenges the mainstream view

that African-Americans have neither a history nor a civilization of

their own. No reader who is familiar with the history of human

civilization would find this poem a difficult one to understand. In this

regard, Hughes' resistance to White hegemony in 'The Negro Speaks of

Rivers' is direct and overt.

'Note on Commercial Theatre,' although thematically akin to 'The

Negro Speaks of Rivers,' is a moderately difficult poem in comparison

with 'The Negro Speaks of Rivers.' As 'The Negro Speaks of Rivers'

reclaims African-Americans' civilizations, 'Note on Commercial Theatre'

reclaims African-Americans' "proprietorship," as it were, of their art

and music, from Europeans. White historians of music wrote that jazz and

the blues, two varieties of music, came from Europe, and thereby denied

African-Americans the heritage of their arts.

Hughes underlines that not only have Europeans and Whites "taken" the

arts belonging to African-Americans but they have also polluted and

blemished the "original" character of those arts by mixing them "with

symphonies." Non-African-American readers unfamiliar with the blues and

the spirituals belonging to African-Americans may require an interpreter

to understand this poem. Non-African-American readers' awareness of the

art forms-the Blues and the spirituals-is, therefore, crucial to their

understanding of this poem. However, one could argue that Hughes, by

drawing non-African-American readers' attention to the art forms

belonging to African-Americans, cautions non-African-American readers

about the misrepresentations in the mainstream accounts of those art

forms written by Whites.

Nikki Giovanni's 'The True Import of Present Dialogue: Black vs.

Negro' is written in a language which may baffle, if not frighten,

readers whose ears are attuned to the "refined" language which is found

in the poetry of mainstream American poets such as Robert Frost and

Wallace Stevens. Giovanni's poem, as noted by Lilamani De Silva, is

"strong" and "militant" (104), for it is skeptical about the idea that

African-Americans can win their freedom through passive resistance and

non-violence:

Nigger

Can you kill

Can you kill

Can a nigger kill

Can a nigger kill a honkie

Can a nigger kill the man

|

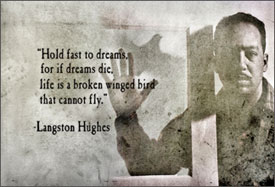

Langston Hughes |

Giovanni does not inscribe this poem in the language of mild protest;

instead, her poem underlines the importance of a language of resistance

which is radical and militant, and a poetic idiom which departs from the

diction of mainstream American poetry. 'The True Import of Present

Dialogue: Black vs. Negro,' therefore, carves a new poetic contour which

is revolutionary in its content and style. The poem urges the reader to

see its refusal to comply with the poetic conventions of mainstream

American poetry as an act of resistance on the part of the

African-American poet. If we regard Giovanni's rejection of the

conventions of diction observed in mainstream American poetry as an act

of resistance, 'The True Import of Present Dialogue: Black vs. Negro'

will certainly make more sense.

Like Giovanni's poem, Lucille Clifton's 'Homage to My Hips' is

radical and unconventional. By "celebrating her hips and singing that

fat is beautiful" (Lilamani De Silva 108), the poet deconstructs the

conventional, race-biased standards by which feminine beauty is valued

and hierarchized in the mainstream cultural systems of American society:

these hips are big hips.

they need space to

move around in.

they don't fit into little

petty places. these hips

are free hips.

they don't like to be held back.

these hips have never been enslaved,

they go where they want to go

they do what they want to do.

these hips are mighty hips.

these hips are magic hips.

i have known them

to put a spell on a man and

spin him like a top!

The poem is counter-hegemonic in two ways in that it asserts the

freedom of both women and African-Americans from male-chauvinism and

White hegemony respectively. Written in a language that is simple,

direct and economical, 'Homage to My Hips,' like Langston Hughes' 'The

Negro Speaks of Rivers,' is less challenging to non-African-American

readers; nevertheless, Clifton expects us to see her attempt to "free"

the poem from complex patterns of versification and language from

capitalization to the themes of celebrating difference and freedom. It

is only when we make connections between the content, structure and

style of 'Homage to My Hips' that we see the emergence of a poetic

expression of resistance which calls simultaneously for the liberation

of two marginalized subject positions- the female and the

African-American.

In 'Kitchenette Building,' Gwendolyn Brooks, another major female

African-American poet, describes the conditions of ghetto living.

Brooks' voice in the poem, unlike Giovanni and Clifton's, is dispirited.

The poem brings to the fore the trials and tribulations of underclass

African-Americans and underscores that the non-availability of the

economic wherewithal necessary for the advancement of African-Americans

has deprived their community of dreams about a better life:

We are things of dry hours and the involuntary plan,

Grayed in, and gray. "Dream" makes a giddy sound, not strong

Like "rent," "feeding a wife," "satisfying a man."

But could a dream sent up through onion fumes

Its white and violet, fight with fried potatoes

And yesterday's garbage ripening in the hall,

Flutter, or sing an aria down these rooms […].

The most pressing realities in the lives of African-Americans,

according to Brooks, are "rent," "satisfying a man," "feeding a wife,"

and the uncleared garbage of the previous day. The "Number Five" in the

last stanza refers not only to the fifth person of a group of

African-Americans sharing the same ghetto and the same bathroom but also

to the nameless, "identity-less" state of African-Americans in the

"White-dominant" United States of America.

As Lilamani de Silva notes, this poem is rooted deeply "in the

specificity of the socio-historical and cultural milieu of the

underclass" (100). For example, according to a commentator, the phrases

"onion fumes" and "fried potatoes" collectively refer to a Southern dish

made by poor Blacks by frying a combination of potatoes and onions. The

commentator also says that "the involuntary plan" denotes "the real

estate plans to exploit Black people, who were moving into formally

White neighborhoods and the break up of formally large, spacious, single

family apartments into shared, cramped, overcrowded spaces for higher

profits" (Anonymous, oldpoetry.com). Non-African-American readers who

are not familiar with these cultural and historical details might face

difficulties in grasping the complete meaning of 'Kitchenette Building.'

However, these references are included in the poem not for the

purpose of confusing non-African-American readers but with a view to

inviting them to see the harsh realities engulfing the lives of

African-Americans, and to understand African-Americans' history and

culture, which White hegemony has carefully concealed beneath the

seemingly all-inclusive captions of "American culture" and "American

history."

Paul Laurence Dunbar's 'The Party' is a poem in which satire is

directed towards African-Americans who, in pursuit of upward social

mobility, blindly mimic their white masters in their dress and manners:

Evahbody dresses deir fines'- Heish yo' mouf an' git away,

Ain't seen sich fancy dressin' sence las' quah'tly meetin'

day;

Gals all dressed in silks an' satins, not a winkle nor a crease,

Eyes a-battin, teeth a-shinin, haih breshed back ez slick ez

grease;

[…]

Men all dressed up in Prince Alberts, swallertails 'u'd tek you'

bref!

[…]

Comin' down de flo' a bowin' an' swayin' an' a-swinging',

Puttin' on huh high-toned mannahs all de time […].

The most difficult aspect of this poem is that it is written in the

dialect spoken by African-Americans. The dialect spoken by

African-Americans is a "non-standard" variety of American English, and

one that is often stigmatized by White speakers of English in the USA.

The poet, by using this non-standard dialect, "legitimizes" the language

spoken by African-Americans, and elevates it to a position equivalent to

that of General American English.

Although readers who are not familiar with this dialect might find

this poem a difficult one, when considering this poem with respect to

Dunbar's statement that "dialect was the only way to get [white] people

listen to me" (Margolies 28), we see that Dunbar's selection of the

dialect spoken by African-Americans to write this poem enables him to

launch his resistance to White hegemony effectively and fittingly in a

language that makes up African-Americans' identity. William Dean Howells

notes that "Dunbar's dialect verse was a representation of reality," and

that "the political import of [the use of the dialect] was unassailable"

(Gates 177). As the language used in the poem serves the Afro-American

poet's political function of emphasizing the role of the dialect in

everyday mass communication of African-Americans, the dialect used in

'The Party' should be seen as a positive requirement of poetic

resistance rather than as a negative limitation curtailing the meaning

making process of non-African-American readers.

As literary vehicles for resistance, the poems discussed above are

"coded and culture-bound" in places (De Silva 99), and therefore

non-African-American readers may find difficulties in understanding

certain sections of the poems which portray the cultural aspects of the

trendy lifestyle of African-Americans and their history. Moreover, the

language used in some poems may appear to readers who are not conversant

with the dialect spoken by African-Americans an obstacle to

understanding the poem. On account of these aspects of African-American

poetry, readers outside the African-American community sometimes require

a class of interpreters to appreciate Afro-American poetry.

The importance of interpreters to non-African-American readers,

however, does not mean that African-American poetry is esoteric or

unintelligible; instead, as argued by Lilamani De Silva, the necessity

for a class of interpreters invites, if not compels,

non-African-American readers, particularly White American readers, to

"consider and appreciate the traumas of black readers who had to try and

belong in a culture that consistently did not write for them,

marginalized, excluded, ignored, or treated them as objects" (105). In

this regard, one could argue that, by creating a need for interpreters

among White American and non-African-American readers, African-American

poets launch their literary resistance to the hegemonic forces operating

against them, their literature and their community, and demand those

forces to recognise that their culture and civilization are not inferior

to any other culture or civilization in the world.

Works Cited

De Silva, Lilamani. "The Poetry of African-American Women: Making

Cultural Difference Meaningful." The Sri Lanka Journal of the

Humanities. XXI (1995): 99-113.

Gates, Jr., Henry Louis. The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of

African-American Literary Criticism. Oxford: Oxford University Press,

1988.

Margolies, Edward. Native Sons: A Critical Study of Twentieth-Century

Negro American Authors. New York: J. B. Lippincott, 1968.

Oldpoetry.com. "Kitchenette Building." 11 Mar. 2009

. |