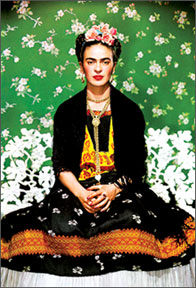

The life and work of Frida Kahlo

Over

a period of several weeks I have been reviewing Latin American films

made during the post-Boom era. Certainly no study of Spanish / American

cinema produced during the second half of the 20th Century would be

complete without investigating the life and art of Frida Kahlo. This

Mexican painter is known as a 20th-century icon who became an

international sensation in the worlds of modern art and radical

politics. In fact Kahlo had a love affair with the Russian revolutionary

leader, Leon Trotsky and then later became a fervent communist. Kahlo is

often described as a Surrealist but vehemently denied it, saying 'They

thought I was a Surrealist but I wasn't. I never painted dreams - I

painted my own reality.' There have been two biographical film versions

made of Frida Kahlo's life; the first in 1983 and the second in 2002. Over

a period of several weeks I have been reviewing Latin American films

made during the post-Boom era. Certainly no study of Spanish / American

cinema produced during the second half of the 20th Century would be

complete without investigating the life and art of Frida Kahlo. This

Mexican painter is known as a 20th-century icon who became an

international sensation in the worlds of modern art and radical

politics. In fact Kahlo had a love affair with the Russian revolutionary

leader, Leon Trotsky and then later became a fervent communist. Kahlo is

often described as a Surrealist but vehemently denied it, saying 'They

thought I was a Surrealist but I wasn't. I never painted dreams - I

painted my own reality.' There have been two biographical film versions

made of Frida Kahlo's life; the first in 1983 and the second in 2002.

Frida Kahlo |

Frida and Diego |

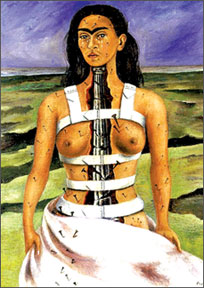

'Frida Broken' |

'Frida Broken'

The 1983 version, 'Frida: naturaleza viva,' directed by Leduc,

starring Ofelia Medina and Jean-Jose Gurrola was beautiful, poetic and

faithful to the spirit of Kahlo's own work. It has a dreamy, surreal

quality and intensity of imagery that is a feast for the senses. In

spite of its fragmented narrative style, it holds together well and the

scenes flow nicely into each other. The viewer gets a good sense of

Frida Kahlo's personality and the major events her life.

However, these elements are not presented in a typical linear form

and it is clear that 'Frida; naturaleza viva' is an art film not aimed

at mainstream audiences. This version was first released and screened in

art cinemas and film festivals. There was considerable excitement among

people who knew of Frida Kahlo and the film was well received, yet its

lack of mass appeal is no surprise. This version of the film has nearly

vanished in the wake of the newer one. It is likely that this is because

in order to understand the plot, knowledge of Frida's life experiences

is essential. The film is rather harrowing, on account of the fact that

it documents many of the difficult and unpleasant experiences in Kahlo's

life. Much of the latter part of the film is a representation of Frida

on her deathbed.

The 2002 version 'Frida' directed by Julie Taymor and starring Salma

Hayek and Antonio Banderas had a completely different agenda. This was

to present Frida to a large audience, who would know nothing of the

Marxist socio-political circles in which Frida moved. In the sixteen

years between the two films, the media thoroughly romanticized and

marketed Kahlo as a pop culture icon. Fueled by Hayden Herrera's 1991

biography of Kahlo, 'The Cult of Frida' Frida's fame spread beyond the

artsy intelligentsia and the market was flooded with Frida posters and

t-shirts. The success of novels/films such as Isabel Allende's, 'La casa

de los espiritus' and Laura Esquivel's 'Like Water for Chocolate' had

primed American audiences for romantic Latin American magical realism.

Kahlo's Surrealist style art appealed to audiences who had watched these

post-Boom style films.

Frida was born in Mexico City in 1907, the third daughter of

Guillermo and Matilda Kahlo. Her father was a photographer of Hungarian

Jewish descent, who had been born in Germany; her mother was a Spanish /

Native American mix. Her life was to be a long series of physical

traumas and the first of these came early. At the age of six she was

stricken with polio, which left her with a limp. Once over the polio,

Kahlo seemed determined to live life to the fullest. She became a tomboy

at school and the leader of a group of rebellious youngsters at the

National Preparatory School they attended. Then in 1925, Kahlo suffered

another tragedy when the school bus on which she was riding collided

with another vehicle. A metal pole pierced her body, leaving her with

multiple injuries including a broken spinal column. During a long

recuperation, Kahlo discovered her love for painting. Using a lap easel

her mother gave her and a mirror she'd had hung in the canopy above her

bed, Kahlo produced some of her earliest self-portraits.

A study of the life and work of Frida Kahlo would not be incomplete

without reference to her husband. Diego Rivera is considered the father

of Mexican mural art as well as modern political art. He reinterpreted

Mexican history from a revolutionary and nationalistic point of view.

Not only did he express powerful ideas in his murals but he also applied

the tools he learned with modernist techniques. Diego Rivera's murals

express his personal ideals by unifying art with politics. In the early

days of their marriage, the public regarded Kahlo chiefly as an

appendage to a famous husband rather than as an artist in her own right.

Their 25-year union would prove to be a stormy one marred by numerous

affairs on both sides. Beautiful, intelligent and immensely talented,

Kahlo was considered one of the most desirable women of her day but the

pain of Kahlo's complex marriage was often reflected in her paintings,

such as one entitled, "Frida y Diego." Although the couple did divorce

in 1939, they reunited in less than a year. For all their troubles, they

remained one another's greatest loves and greatest fans. Kahlo said

later 'I suffered two grave accidents in my life. One in which a

streetcar knocked me down... The other accident is Diego.'

In 1932 Rivera had been commissioned to paint a major series of

murals for the Detroit Museum and whilst there, Kahlo suffered a

miscarriage. While recovering, she painted 'Miscarriage in Detroit', one

of her truly penetrating self-portraits. The style she evolved at this

time was entirely unlike that of her husband. From Detroit they went to

New York, where Rivera had been commissioned to paint a mural in the

Rockefeller Center. The commission erupted into an enormous scandal,

when the patron ordered the half-completed work destroyed because of the

political imagery. However, Rivera lingered in the United States which

he loved and Kahlo now loathed. When they finally returned to Mexico in

1935, Rivera embarked on an affair with Kahlo's younger sister Cristina.

Rivera had never been faithful to any woman but now Kahlo embarked on a

series of affairs with both men and women which were to continue for the

rest of her life. (Rivera tolerated her lesbian relationships better

than he did the heterosexual ones, which made him violently jealous).

Her health grew visibly worse from 1944 onwards and Kahlo underwent

the first many operations on her spine and crippled foot. Interestingly

her artistic reputation continued to grow more rapidly in the United

States than in Mexico. She was included in prestigious group shows in

the Museum of Modern Art, the Boston Institute of Contemporary Arts and

the Philadelphia Museum of Art. In 1946, however, she received a Mexican

government fellowship, and in the same year an official prize on the

occasion of the Annual National Exhibition. She also took up teaching at

the new experimental art school 'La Esmeralda', and despite her

unconventional methods, was an inspiration to her students. After her

return home from hospital, Kahlo became an increasingly fervent and

impassioned Communist. Rivera had been expelled from the Party, which

was reluctant to receive him back, both because of his links with the

Mexican government of the day, and because of his association with

Trotsky. Kahlo boasted: 'I was a member of the Party before I met Diego

and I think I am a better Communist than he is or ever will be.'

While the 1940s had seen her produce some of her finest work, her

paintings now became more clumsy and chaotic, thanks to the joint

effects of pain, drugs and drink. Despite this, in 1953 she was offered

her first solo show in Mexico itself - which was to be the only such

show held in her own lifetime. It took place at the fashionable Galeria

de Arte Contemporaneo in the Zona Rosa of Mexico City. At first it

seemed that Kahlo would be too ill to attend but she sent her richly

decorated fourposter bed ahead of her and arrived by ambulance. She was

carried into the gallery on a stretcher and it was a triumphal occasion.

In the same year, Kahlo had her right leg amputated below the knee,

due to gangrene. It was a tremendous blow to someone who had invested so

much in the elaboration of her own self image. She learned to walk again

with an artificial limb, and even (briefly and with the help of

pain-killing drugs) danced at celebrations with friends. However, the

end of her life was close. In July 1954, she made a last public

appearance, when she participated in a Communist demonstration against

the overthrow of the left-wing Guatemalan president Jacobo Arbenz. She

died in her sleep soon afterwards, apparently as the result of an

embolism. However there was suspicion among those close to her that she

had found a way to commit suicide. Her last diary entry read 'I hope the

end is joyful - and I hope never to come back - Frida'

Both the 1983 version and the 2002 version of the film are accurate

portrayals of Frida and Diego's life together in 'La Casa Azul' (The

Blue House). This is where Frida spent her childhood and the final years

of her life. Since her death, the house has been turned into a museum

where visitors can admire many of the rooms, decorated in Frida's own

unique style. During her life and through her art, Frida Kahlo came to

typify 'La Mexicana' (The Mexican Woman) and she was proud of her

culture and Mexico's pre-Spanish heritage. Since she was the daughter of

a European/Jewish Father and an indigineous American / Spanish mother,

she was a true Latin American.

Both films contain a few minor inaccuracies, yet on the whole, they

both give the audience a very good idea of the trials, triumphs,

characters and work of both Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. Next week, I

shall review and explore the context and meaning behind some of Frida's

most famous paintings, which accurately document the key events and

emotions throughout her life with Diego Rivera. |