|

Australian indigenous literature:

From White representation to self representation

by Sunili UTHPALAWANNA GOVINNAGE and Sunil GOVINNAGE

********* *********

Aboriginal achievement

Is like the

dark side of the mood,

For it is there

But so little known.

-Ernie Dingo

**********

|

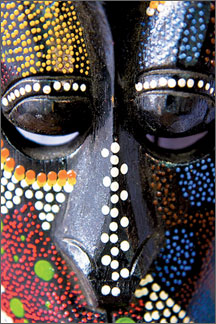

Aboriginal people of Australia

|

Literature is a powerful cultural artefact, which can communicate

stories of a group or people to others. The process of writing and

telling stories allows the creators to represent both their individual

and group identity. Conversely, a dominant group can use the power of

the written word to suppress another group by depicting it as the

inferior and or different "other." In the area of colonial and

indigenous relations, the response of the subordinate group is the

domain of postcolonial studies - the questioning of the normalisation of

the dominant group's power and "the social, political, economic, and

cultural practices which arise in response and resistance to

colonialism."

The dynamics of a group's literary representation and

self-representation can be used to explore the power relations that

exist within a society. In this article, we will examine the way

representation and self-representation of a marginalised group between

the settler and indigenous populations in Australia.

we will observe how the period of representation illustrates the

balance of power relations in the direction of the Whites, who were able

to present their views of Aboriginal peoples in literature. We will then

present a shift in power relations as indigenous people began to assert

their rights and their own identity (as opposed to an assigned identity)

which coincides with the emergence of self-representative texts in

Australian literary canon.

Australian indigenous creative writing cannot be studied in a vacuum,

but rather needs to be examined and understood within the social and

historical contexts. The changing socio-political status of indigenous

people can be linked to the expansion of indigenous prose, poetry and

drama and similarly, the "native literature of each country … assert[ing]

cultural autonomy and sovereignty in a fascinating way."

The journey from representation to self-representation can be seen as

a way in which the Aborigines were initially depicted as "inferior" and

or "lower caste" group through an assigned identity of the "other."

Self-representation in literature has allowed indigenous peoples to

speak with their own voices, instead of being spoken about. Conversely,

a dominant group can use the power of the written word to suppress

another group by depicting it as the inferior and or different "other"

as evident in Australia.

Communication of silence

In order to establish a framework for this paper, first, we would

like to provide an insight from recent Australian history relating to

the arrival of British invaders in 1770. Healy (1985:203) who has

written on Australian literary canon provides fascinating observations

on the early encounters between the white invaders and the Aborigines

based on historical documents:

"On 23 July 1770 a straggler from one of Cook's shore parties fell in

with four Aborigines sitting by a fire. He had the intelligence not to

panic. They felt his body to make sure that he was a man like

themselves. There could be no language between them." (Healy, 1985:

203).

Healy further elaborates this language barrier in terms of

"communication of silence" between these two races: "Communication

between the two races began from this silence. The Aborigines had

touched the white man. Cook's journal showed the other part of the

process. His vocabulary of Aboriginal words was the first attempt to

understand the Aborigine. He recorded thirty-nine words reproduced the

simplicity of the Aboriginal touch. Most of the words were anatomical

..." (Healy, 1985: 203)

From our perspective, Healy's words that there "could be no language

between them" is crucial as the language and cultural barriers which

evolved during the last two hundred years have kept the white

Australians and the Aborigines in two separate compartments pulling each

other in different directions.

These cultural compartments have created issues such as land rights,

disempowerment, and the children of "stolen generation." In our view,

this cultural compartmentalisation has contributed to develop different

perspectives of the "other" in Australian literary canon, and may be

interpreted as "Orientalism."

The

Construction of "the Other" in Australian Edward Said (1979) writes

about the practices adopted by colonial powers "to construct the

colonised Other." Although Said's (1979) study limits Orientalism on how

English, French, and American scholars have approached the Arab

societies of North Africa and the Middle East, in this paper we use the

term "Orientalism" as a representation of class of practices adopted by

colonial powers "to construct the colonised Other." The

Construction of "the Other" in Australian Edward Said (1979) writes

about the practices adopted by colonial powers "to construct the

colonised Other." Although Said's (1979) study limits Orientalism on how

English, French, and American scholars have approached the Arab

societies of North Africa and the Middle East, in this paper we use the

term "Orientalism" as a representation of class of practices adopted by

colonial powers "to construct the colonised Other."

One of the central themes of this theory is that "the Other cannot

(be allowed to) represent themselves, cannot even be supposed to know

themselves as subjects or objects of the discourse" and because of this,

"they must therefore be represented by others."

Hodge and Mishra (1991) have applied this theory to Australia using

the term "Aboriginalism"; a process that encodes "smugness and a sense

of superiority, racist stereotypes, and assertion of rights of ownership

in the intellectual and cultural sphere to match power in the political

and economic spheres." What "Aboriginalism" does is prevent Aborigines

from asserting the authority to be the authors of their own meanings,

and it renders them unable to influence representations and perceptions

of themselves.

The representation of Aboriginal people in early Australian

literature is a construction of the colonised "Other" by the white

Anglo-Celtic writers. For example, Katherine S. Prichard captured an

Aboriginal theme in one of her short stories entitled "Marlene" (1941).

Dialogue between the white protagonists and Aboriginal characters in the

story embodies an interpretation of the inferior nature of so-called

"half-caste" Aborigines, who are described as "fat," "barefooted," and

unclean:

"Where'd we shift to?" a fat, youngish woman asked jocosely.

Barefooted, she stood, a once-white dress dragged across her heavy

breast..."

When representing the so-called negative qualities of Aboriginal

people in literary texts, Daisy Bates' The Passing of the Aborigines is

a case in point. First published in 1938, Bates presented outright myths

and incorrect stereotypes such as infanticide cannibalistic practices of

Aboriginal tribes in Western Australia. The text, which went through

several reprints in two editions (there was a reprint as recently 1972),

has been described as "the most destructive book written on Aborigines."

Further negative representation of Indigenous Australians comes through

in the 1841 children's story, "A Mother's Offering to Her Children,"

attributed to "A Lady Long Resident in New South Wales." In the process

of telling her children a bedtime story, Mrs. S states:

"These poor uncivilised people, most frequently meet with some

deplorable end, through giving away to unrestrained passions."

This passage illustrates not only the triviality assigned to

Aboriginal people by the White settlers, but the negative and

stereotypical attitudes that were felt about them.

Sympathetic and sensitive portrayals of Aboriginal people Somewhat

sympathetic and sensitive portrayals of Aboriginal people are found in

Prichard's Coronado: The Well in the Shadow (1929) and Xavier Herbert's

Capricornia (1975). While the books gained favourable critical appraisal

(particularly overseas), the negative response of the Australian public

showed that the texts were ahead of their time in exploring interracial

relations. As Shoemaker writes:

"The social and political conditions which prevailed between 1929 and

1945 militated against either Coonardoo or Capricornia having a

significant educative impact on racial prejudice and Aboriginal

stereotypes."

This was the era of segregation, force assimilation, legislative

"protection" and child removal. It was the Whites who had power to

control the representation of Aborigines, which was a negative one more

often than not. When representation was positive, however, the

prevailing values and attitudes of society rejected them in favour of

encoded stereotypes.

The reason why "so little [was] known" about Aboriginal people as

they saw themselves is that the period of representation assigned

meanings to them, rather than letting them speak on their own. David

Unaipon (1930) published several works in the first half of the

twentieth century, but his work was not widely distributed or publicised-his

1929 manuscript Legendary Tales of the Australian Aborigine was

published in 1930, but as Myths and Legends of the Australian Aborigines

by anthropologist William Ramsay Smith without any attribution to or

recognition of the actual author and no other Indigenous Australians

were published until the 1960s. Davis and Shoemaker assert that the

reason for this was the rudimentary and predominantly vocational

education received by Aboriginal Australians at the time, and that

"poverty stricken Aborigines were far more concerned with survival than

with creative expression in the Western format.

Political Change and Cultural Transformation

The turning point of the movement from representation to

self-representation in Australian Aboriginal literature can be seen in

the 1960s. Within months, two of the most pivotal and landmark pieces of

Aboriginal literature were published: Oodgeroo Noonuccal's (formerly

Kath Walker) first collection of poetry, We Are Going, in 1964 and

Mudrooroo's (formerly Colin Johnson) first novel, Wild Cat Falling, of

1965. These two works not only gained critical acclaim but also did well

commercially; Oodgeroo's volume being reprinted seven times in seven

months and Mudrooroo's novel has been continually in print.

The emerging indigenous writers displayed a response to the colonial

and Other representations made of their group by analysing, judging and

criticising normalised practices. Oodgeroo Noonuccal's "Aboriginal

Charter of Rights" presents a manifesto for social, political, cultural

and economic change:

We want hope, not racialism,

Brotherhood, not ostracism,

Black advance, not white ascendance,

Make us equals not dependants.

We need help, not exploitation,

We want freedom, not frustration;

Not control, but self-reliance,

Independence, not compliance…

(Kath Walker, We Are Going, (Brisbane: Jacaranda Press, 1964: 9)

This assertion of rights is a clear example of the way in which the

Other can challenge the previous ideology of the coloniser by directly

addressing the racism and subjugation encoded in the social, political

and economic spheres. Mudrooroo's novel is written in a similar manner.

The main character is a nameless, aimless and helpless aboriginal youth

whose story begins with him being released from prison, only to be

returned at the end, confirming white expectations and the circular

patterns of Aboriginal experiences. (Hodge and Mishra, Dark Side of the

Dream: p.109) The youth's situation can be deconstructed to illustrate

the lack of hope facing Aboriginal youth caught up in alcohol, violence

and crime.

The emergence of self-representative Aboriginal texts at this time is

significant. The 1960's and beyond saw issues of Aboriginal social

justice rising in importance, from the land rights debate - as shown by

the Yirrkala people of Australia's (Northern Territory) Arnhem Land's

paper bark petition to the House of Representatives (1963) - and the

granting of citizenship and suffrage to Indigenous Australians (1967) to

the establishment of Aboriginal Legal Services (1970) and the infamous

Tent Embassy protest (1972). Further advances in Black Australian

literature coincided with the 1982 Commonwealth Games and the

Bicentenary in 1988, with the resulting international attention

providing means for indigenous people to get their message across.

Shoemaker contends that there is a fundamental relationship between

the change in the socio-political situation of Australian Aborigines and

indigenous creative writing in English: "Dramatic-and overdue-changes in

the legislative status of Aborigines paralleled the experiments of Black

Australian literature during those years." (Shoemaker, Black Words White

Page: p. 6) The pattern of major upheavals concerning the

socio-political status of native people being accompanied by "an

explosion in literary production" was also seen during the lead-up and

the aftermath to the passage of the 1975 Treaty of Waitangi Act in New

Zealand and in the environment of the Oka confrontation in Quebec,

Canada in 1990.

Self-representation of indigenous peoples' literature in Australia

provides the rest of the community "the opportunity to obtain a glimpse

of [indigenous peoples] as they see themselves, rather than as they are

seen by others." (Shoemaker, Black Words White Page: p4).

Australian Aboriginal culture is distinctively oral, and the lore and

law of the peoples was communicated though stories and songs as well as

art and dance. The intricacies of Indigenous communication go far beyond

the scope of this short paper, but the use of the English language in

self-representative texts is an interesting aspect of indigenous

literature. The power of the coloniser's language initially suppressed

indigenous people by disabling them from portraying their own identity.

Through self-representation however, Aboriginal writers were able to

tell their own stories with their own voices, and by using the

coloniser's language to do this, they are able to get their stories

across to the people who once marginalised them.

By adopting Western literary paradigms and then manipulating them by

incorporating traditional narrative elements, indigenous authors have a

powerful political tool:

"Aboriginal writers … use (White) literary genres as a political

weapon with which to challenge White hegemony. They … redefine genres,

explode discourses, delegitimate [sic] standard English, subvert

expectations, challenge assumptions… (Hodge and Mishra, Dark Side of the

Dream: 115.)

In Australian Aboriginal poetry, the use of repetition similar to

traditional song cycles illustrates creative forms of the oppressed

being employed to assert their independence and identity, for example in

Mudrooroo's The Song Circle of Jacky, published in 1986. Australia's

South West Noongar people's words and phrases are abundant in the

dialogue of Jack Davis's play No Sugar (1985), which uses a White genre

(drama) to present history from the point of view of the marginalised

and oppressed other. Often the English language is not so much imperial

as it is inadequate in conveying the complexities or native cultures and

the effect of Aboriginal words within English language texts not only

overcomes this problem but also subverts any colonial power language has

over indigenous representation.

Conclusion

By reading texts we can read, understand and interpret cultures.

Indigenous writers and their works "are one of the clearest

manifestations of the process whereby native peoples have achieved

so-called mainstream recognition." The development of cross-cultural

communication has reflected the changes in the socio-political status of

indigenous peoples. The period of representation illustrates the balance

of power relations in the direction of the Whites, who were able to

present their views of native peoples in literature, while the native

people themselves could not do this.

The shift in power relations as indigenous people began to assert

their rights and their own identity (as opposed to an assigned identity)

coincides with the emergence of self-representative texts. By using

their own voices, Aboriginal now able to present portrayals of

themselves and transform the way they are seen by others. Literature

enables indigenous cultures to showcase their achievements, and as

societal changes continue, we are able to see light shed onto what Ernie

Dingo calls "the dark side of the moon."

(About Authors: Sunili Uthpalawanna

Govinnage is an Australian Lawyer. Sunil Govinnage is a Sri

Lankan/Australian poet).

|