The Confession

by Sunethra Attanayake

I felt a sense of premonition

that somebody would seize me by the neck if I attended the funeral since

I was considered a family outcast. She must be lying peacefully at the

funeral parlour wearing her usual osari with a puffed sleeved jacket and

a string of beads around her neck to match.

I cannot deny the fact that she contributed wholeheartedly to my

intellectual and emotional well-being by sending me to a leading school.

Moreover, only on one occasion she encouraged me ending up with chat-up

statements such as “You are exemplary, you can outdo others, keep it

up!” When I was growing up, she just gave me an idea about matrimony and

emphasised on education and home background as matrimonial

considerations whereas I was blinded to act on my own accord despite her

advice.

In spite of that, she forgave me instinctively. Whenever I felt

miserable being unable to meet both ends, I was compelled to stretch my

hand towards her benevolent hand. She made my family comfortable. Her

outpouring was always about her loneliness, monotony, boredom and

anticipation ever since I joined my career as a big man. As such, I

wondered how she could manage to get over them at the Elder’s Home.

Her days would have been more stressful and immensely sorrowful

there. Her days would have been more stressful and immensely sorrowful

there.

Now, where could be the pretty collection of my baby-smocked, cross

stitched embroidered in French patterns and fringed. Besides, a remnant

of a green sarong that I wore for the first time in my life on my eighth

birthday.

This collection was the one and only valuable possession she had in

the lowest shelf of our antique cupboard, among quite a number of

naphthalene balls.

A television footage is focused in front of my eyes highlighting a

sinful occurrence along with some other fragrant reminiscences of a

golden era. The main role of the plot is displayed by my wife Shammi

over a trivial dispute.

The lonely house of my mother is the location. She seizes my mother

by the neck - I’m too provoked and my robust right hand is raised to

approach my mother’s cheek. She doesn’t utter a single word.

The plot reaches its anti-climax when three unexpected witnesses

appear all of a sudden. A vehicle with the state emblem is parked at the

gate. My three children and the driver peep through its shutters.

Shammi

dashes with mother’s belongings on the floor. Water’s spilled on the

floor. “Umba merunama api enne ne,” she says.

It’s a predicament. Mother is stunned. The wooden spoon that she had

in her hand has dropped. A served plate of rice is left on the table. A

pan of gravy is on the ember. Tommie trembles with fear under the table.

The jasmine flowers offered to the Buddha in the morning are scattered

on the cement. To wind up, Shammi kicks the garden gate and gets into

the vehicle like a queen. It’s a predicament. Mother is stunned. The wooden spoon that she had

in her hand has dropped. A served plate of rice is left on the table. A

pan of gravy is on the ember. Tommie trembles with fear under the table.

The jasmine flowers offered to the Buddha in the morning are scattered

on the cement. To wind up, Shammi kicks the garden gate and gets into

the vehicle like a queen.

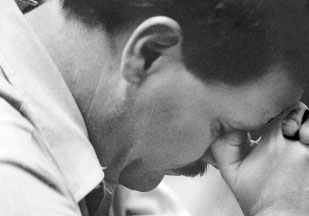

I felt the cascading television footage winding around starting from

my feet up to the neck tightly. How can I move? Will I be able to

breathe? “Thaththi, do you know that your mother has died?” my sixteen

year-old daughter asks showing me a caricature of the corpse of my

mother drawn by her.

Do please forgive me Amma. |