|

An Move to solve human - elephant conflict :

Homogeneous human habitat vital

By Dhaneshi YATAWARA

|

Data on elephant habitat is essential to prevent unnecessary

blockage to elephant movements in the national development

drive.

|

Today humans have lost the fascinating symbiosis they had with

elephants over generations. Human ancestors fearlessly crossed the thick

jungles, the home of the Sri Lankan elephant. Yet today, there are media

reports on human deaths due to the human elephant conflict. Does this

mean elephants have become a threat to human existence?

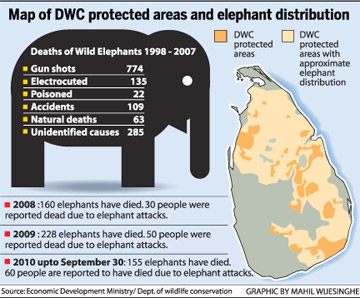

According to statistics of the Department of Wildlife, in 2008

elephants killed 30 people and 50 in 2009. In 2010 up to September 30,

the number of people killed by elephants is 60.

Looking at the main causes for human deaths in Sri Lanka according to

statistics of the Ministry of Health, 39,321 cases of snake bites and 91

deaths have been reported in 2007.

Around 100 deaths and 39,793 cases of snake bites were reported in

2006. Looks like a large number! Then, did you know that 2054 people

have died due to liver diseases in 2007 and 1,888 have died in 2006.

Deaths due to diseases in liver was 2,695 in 2003, 2,631 in 2004 and

2,274 in 2005.

|

The end result of any development in elephant habitat should be

homogeneous human habitat with a clear boundary for elephants. |

Accordingly, due to Ischaemic heart diseases 3,762 people have died

in 2005, 4,125 in 2006 and another 4,536 in 2007. In comparison it is

obvious that elephants are not bringing devastation to the human

population as many illnesses do.

The elephant is the insignia of the evergreen environment and a deep

rooted culture. To a Sri Lankan, a Perehera is never complete without a

retinue of elephants.

Yet, today the humans and elephants conflict has aggravated. The

reason is mainly due to the loss of habitat caused by fragmentation of

land for needs of humans. Encroaching the limited elephant habitat by

humans is making this majestic beast homeless.

Forest

The Sri Lankan Elephant, ‘Elephas maximus maximus’ once roamed in

every eco-region of this island nation from the cloud forests of the

montane regions to the lowland rainforests and the dry zone forests.

These majestic beasts, the largest of the Asian Elephant genus, today

live in the rainforests and the dry zone forests.

As historical records depict the dwarf elephant that lived in the

montane forests are reported to have gone extinct as a result of the

hunting games of British Colonists.

In the colonial era montane forests became popular game parks of the

British and one of the well-known one was the Horton Plains.

Today killing an elephant carries a death penalty. Even those days

people believed killing the majestic and intelligent beast would bring

God’s curse to the hunter.

As history records Major Thomas Roger, a British hunter who killed

over 1,400 elephants in Montane cloud forests for entertainment, died

struck by lightening. People believe that Gods punished Rogers. Even

after his death his broken tomb stone behind the Nuwara Eliya cemetery

had been struck by lightening twice.

Today in Sri Lanka killing elephants carry a death penalty.

Elephant habitat is restricted to few national parks and reserves

specially in Udawalawe, Yala, Wilpattu, Minneriya and Kaudulla. The

threat faced by Sri Lankan elephants is common to all Asian elephants.

It is encroachment in to their habitats and ancestral moving tracks

which are called as elephant corridors.

Conflict

“Translocating elephants that disturb human settlements never brought

a solution to the human-elephant conflict though it was one of the

solutions for the problem,” said Dr. Chandrawansa Pathiraja, Director

General/ Wildlife, Zoological and Botanical Gardens, Economic

Development Ministry. “Instead of ad hoc methods tried so far the

Governments effort is to implement programs to improve the coexistence

between humans and elephants,” Dr. Pathiraja said.

Elephants strictly follow their age old traditions when humans are

comfortable in changing our heritage. Throughout their life, elephant

herds mostly lead by the matriarch, trek only on these traditional

paths.

In Sri Lanka herds are reported to have ‘nursing units’ consisting

lactating females and their young as well as juvenile care units - which

consists of females with juveniles.

Thus in such an over protective herd, the elephants sees only a

villain in whatever obstruction they encounter in their traditional

routes be it either a electric fence or a village.

Action plan

The Action Plan, a sustainable solution to the existing

human-elephant conflict, drafted by Wildlife authorities under the

purview of the Economic Development Minister Basil Rajapaksa, was handed

over to President Mahinda Rajapaksa recently.

Authorities proposed in the Action Plan new methods such as hormone

treatments and establishing holding grounds for wild elephants causing

problems.

In its long, mid and short term solutions the Action Plan states that

electric fencing to be introduced where necessary.

The Action Plan’s short-term recommendations specifies actions that

will provide immediate relief from human-elephant conflict.

The mid term plan will help develop a comprehensive management

strategy that will effectively address the human-elephant conflict and

bring it down to manageable levels in selected areas.

The long-term action plan suggests strategies that will prevent the

escalation of the conflict and its spread to other new areas.

Authorities plan to appoint a task force to monitor the progress of the

plan.

“While trying to save the humans it is equally important to protect

the elephant habitats as well as their tracks.

Thus the action plan suggests directives to be introduced to combat

encroachments into state lands for cultivation,” Dr. Pathiraja further

said.

The human-elephant conflict has emerged as a result of factors such

as the reduction of forest cover, planned and unplanned land based

development activities, increase in the elephant population during the

past decades thus the National Development plan under the Mahinda

Chinthanaya has recognised the importance of solving the human-elephant

conflict. A practical solution has been proposed to minimize the

human-elephant conflict in consultation with relevant authorities,

experts and other agencies.

According to the Action Plan, over 70% of elephants live outside the

Wildlife Conservation Department’s protected areas. The loss to crop and

property from elephant raiding has become a major socio-economic issue

in a larger part of the dry zone. “Elephant drives and capture-transport

in the current context are not effective in mitigating human-elephant

conflict or conserving elephants,” said Dr. Pathiraja.

Earlier the two main methods of removing elephants from outside

protected areas have been ‘elephant drives’ - removing elephant herds

composed of females and young and the capture-transport of individual

males in to protected areas. Yet at times monitoring of herds restricted

to protected areas have shown that ‘successful’ drives are extremely

detrimental to elephant conservation. The problem is that most adult

males and some herds remain even after a elephant drive. It is observed

that elephant herds and adult males can aggressive and will not fear

crackers.

Elephants, particularly adult males who are captured and translocated,

return to their habitat. Restricting elephants to protected zones

resulted in setting up electric fences. In many cases the electric fence

was put up between the Wildlife Conservation Department’s protected

areas and the Forest Department lands as lands adjacent to protected

areas mostly belong to the Forest Department.

Chena cultivation

The Action Plan indicates that nearly 50% of current electric fences

are put up in this land. This has resulted in elephants living in both

sides of the fence making the electric fence ineffective. The new

approach suggests, the effective prevention of elephants entering in to

developed areas, will be done by installing and effectively maintaining

electric fences at the boundary between elephant conservation areas and

developed areas. The recommendation is to construct village electric

fences in affected areas to protect villages from elephant attacks.

Identification of villages that are to be protected can be done through

Divisional Secretariats via the ‘Gajamithuro’ program.

Currently chena cultivation is illegal in Sri Lanka as it is mostly

done in state land. Chena lands support very high densities of elephants

as a habitat with a high volume of food. ‘Pioneer species’ of plants

grow rapidly in fallow chenas in the dry season and year round in these

abandoned chenas. These pioneer species of plants are a important source

of food for elephants and consequently chena land supports very high

densities of elephants. Therefore, chena lands are of great importance

to maintain large numbers of elephants.

The National Policy does not promote the expansion of chena practices

as this conversion of forest to cultivating land is detrimental to the

biodiversity in general. The recommendation is to preserve chena

practice where it currently occurs, and prevent conversion of chena

areas to permanent settlements and cultivations.

The Action Plan suggests that such areas should be administered as

Managed Elephant Ranges where people will receive economic benefits

linked to elephant conservation, compensation and protection from

elephant depredation. It is also suggested that insurance and

compensation to be reviewed in terms of prevailing market value and made

accessible to the villagers.

Another suggestion in the Action Plan is to develop the elephant

holding grounds as tourist attractions while continuously monitoring

elephants.

Human-elephant conflict mitigation is one of the five components

under the World Bank funded ‘Eco-Systems Conservation and Management

Project’ (ESCAMP) jointly implemented by the Department of Wildlife

Conservation and Forest Department. The project will try out the

approach advocated by the ‘National Policy for the Conservation and

Management of Wild Elephants’ attempting to manage elephants both in and

out of protected areas stretching over a five-year period.

Two areas have been identified in the Action Plan for this purpose -

the greater Hambantota area in the South and the Galgamuwa area in the

north-west.

The long-term Action Plan suggests preventing elephants entering into

developed areas with permanent habitations and cultivations by

installing and effectively maintaining electric fences at the boundary

between elephant habitat and developed areas. The chena areas will be

Managed Elephant Ranges, as stated earlier, with economic benefits

linked to elephant conservation. Assessing alternate barriers such as

biological fences and ditches, alternative crop protection methods are

also considered.

Long-term plans

Developing elephant viewing tourism that benefits local communities

is another suggestion in the Action Plan. In addition, information

required for the mitigation plan will be collected countrywide through

local authorities and the Gajamithuro program and will include data on

the distribution and movement patterns of elephants and effectiveness of

mitigation measures.

Data on elephant habitat use based on radio telemetry is essential to

prevent unnecessary blockage to elephant movement patterns in the

national development drive. An example of land- use planning taking into

consideration elephant ecology, existing land use patterns, and needs of

development is the zoning plan developed by the Urban developmental

Authority (UDA) and the Central Environmental Authority (CEA) Strategic

Environmental Assessment process for the greater Hambantota area.

The Action Plan suggests the involvement of direct agencies involved

in developing land use plans, such as the Urban Development Authority (UDA),

National Physical Planning Department (NPPD), Land-Use Policy Planning

Division (LUPPD) of the Department of Agriculture, to take into account

elephant presence when land-use planning is conducted.

The elephant distribution data necessary for this has to be obtained

by the Department of Wildlife Conservation as stated in the mid-term

Action Plans. The end result of any development in areas with elephants

should be homogeneous human habitat with a hard boundary with elephant

habitat.

As the Action Plan states, currently only a small number of tourists

visit Sri Lanka for its wildlife, but Sri Lanka has the potential to be

the premier wildlife tourist destination in Asia and elephants are an

ideal ‘flagship species’ to achieve this. Sri Lanka is one of the few

countries in the world where elephants can be observed in wilderness.

It is pointed out in the Action Plan that implementing a system to

control human - elephant conflict will allow Sri Lanka to continue to

maintain the current population of Asian elephants that represent over

10% of the global population at a density very much higher than other

Countries.

Instead of making elephants a burden to the country Sri Lanka can

gain great economic benefit by promoting tourism based on elephant

viewing and their co-existence with humans. Such approach will not only

result a successful mitigation program for the human elephant conflict

but will also provide relief for the poor villager from his burning

socio-economic issues.

|