|

Dictator novels:

Llosa's life and times

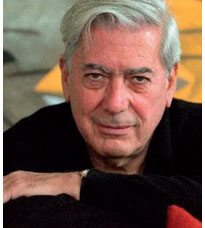

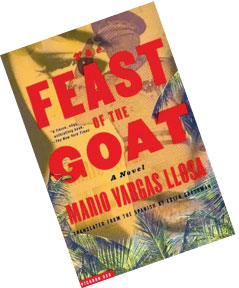

In last week's 'Boom and Beyond' column, I gave a general overview of

Dictator Novels by Latin America writers in response to various

dictatorships. Mario Vargas Llosa was among the authors specifically

mentioned in the column and this was in connection with his best seller

' The feast of the goat'. It is a coincidence that the announcement of

his 2010 Nobel Prize for Literature came a couple of days later. It

therefore seems fitting to dedicate this week's column to Vargas Llosa's

life and writings. In last week's 'Boom and Beyond' column, I gave a general overview of

Dictator Novels by Latin America writers in response to various

dictatorships. Mario Vargas Llosa was among the authors specifically

mentioned in the column and this was in connection with his best seller

' The feast of the goat'. It is a coincidence that the announcement of

his 2010 Nobel Prize for Literature came a couple of days later. It

therefore seems fitting to dedicate this week's column to Vargas Llosa's

life and writings.

Mario Vargas Llosa was born on March 28, 1936, in the southern

Peruvian city of Arequipa. For the first 10 years of his life he lived

in Cochabamba, Bolivia, with his mother and grandparents. He returned to

Peru in 1946 when his parents, who had divorced shortly before his

birth, were reunited. The family settled in Magdalena del Mar, a

middle-class Lima suburb.By the time he was 16, Llosa was working

part-time for several Lima tabloids, mainly covering crime stories. His

first book, ' Los Jefes', a collection of short stories, was published

in 1958 when he was 22.

These years proved to be difficult for Vargas Llosa, since he and his

father did not see eye to eye on his writing ambitions. "We were

opposites and we did not respect each other," he said. "In Bolivia when

I wrote, my grandparents and mother praised me for it. When my father

discovered that I was a writer, he had the opposite reaction. The

bourgeoisie of Lima scorned literature -they considered it an alibi for

idlers, an activity of the upper class." Fearful that his son was in

danger of losing his virility because of his passion for writing, Vargas

Llosa's father shipped him off to Leoncio Prado, an institution that the

author described as half reform school and half college, run by fanatics

of military discipline. "It was the discovery of hell for me," Vargas

Llosa said. "I understood what Darwin's theory meant in the struggle for

life." These years proved to be difficult for Vargas Llosa, since he and his

father did not see eye to eye on his writing ambitions. "We were

opposites and we did not respect each other," he said. "In Bolivia when

I wrote, my grandparents and mother praised me for it. When my father

discovered that I was a writer, he had the opposite reaction. The

bourgeoisie of Lima scorned literature -they considered it an alibi for

idlers, an activity of the upper class." Fearful that his son was in

danger of losing his virility because of his passion for writing, Vargas

Llosa's father shipped him off to Leoncio Prado, an institution that the

author described as half reform school and half college, run by fanatics

of military discipline. "It was the discovery of hell for me," Vargas

Llosa said. "I understood what Darwin's theory meant in the struggle for

life."

The painful experiences at Leoncio Prado were the basis for his first

novel, 'The Time of the Hero' (1963). The work gained instant notoriety

when Peruvian military leaders condemned it and burned one thousand

copies in the courtyard of Leoncio Prado. Praised for its stylistic and

innovative craftsmanship, the novel presented a story of official

corruption and cruelty in a military institution. It won several major

literary awards in Europe and quickly established Vargas Llosa's

reputation as social critic and writer.

His next two novels were 'The Green House' (1969), a magical

realistic tale of an enchanted brothel, and ' 'Conversation in the

Cathedral' (1969), a narrative of the moral depravity of life in Peru

during the 1950s under dictator Manuel Odria. Both books provided

further variations on his themes of hypocrisy and corruption in Peruvian

society and politics.

In 1973 Vargas Llosa published his first humorous novel, 'Captain

Pantoja and the Special Service'. It was a black comedy about a naive

army officer who diligently obeys his commanding officers' order to

organize a group of prostitutes to service soldiers in desolate jungle

camps. The novel depicted the author's continual disdain for military

bureaucracy and incompetence with caustic wit.

Four years later his most internationally popular (and most

autobiographical), novel, 'Aunt Julia and The Scriptwriter' was

published. The semi-fictional, semi-autobiographical Mario is a young

student and would-be writer, whose careers and aspirations are disrupted

when he falls in love with his aunt-in-law. Pedro Camacho, an eccentric

Bolivian scriptwriter, has been hired at the radio station where Mario

works.

The youth envies the prodigious output of Pedro's intricate soap

operas. He hopes to learn from his new mentor the secrets of being an

artist. The chapters alternate between descriptions of Mario's amusing

and increasingly complicated life and Pedro's formulaic and decreasingly

coherent scripts, as each character is gradually overwhelmed by the

burdens and expectations they've created for themselves.

On a deeper level, "Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter" is about

artistic failure. Mario's writing suffers because he is too busy living

life to the fullest, while Pedro's well-being deteriorates because he

barely experiences life at all. While Mario's life is the stuff of

literature, his attempts at short fiction are overly concerned with

artistic affectation. The final chapter completes this theme - the

writer who balances a passion for life and devotion to art is the one

who ultimately succeeds.

This device of multiple-level storytelling from the point of view of

widely divergent characters is a hallmark of Vargas Llosa's work. Most

critics agree that the structures of his next two overtly political

novels, ' War at the End of the World' (1981) and 'The Real Life of

Alejandro Mayta' (1984) were shaped by it. In 1986 Vargas Llosa turned

his hand to detective fiction and wrote the fast-paced cops and killer

thriller ' Who Killed Palomino Molera' . Although the novel lacked the

thickly layered narrative scope of his other works, it clearly proved

the author's talents for writing sordid detail and earthy, comic

dialogue. This device of multiple-level storytelling from the point of view of

widely divergent characters is a hallmark of Vargas Llosa's work. Most

critics agree that the structures of his next two overtly political

novels, ' War at the End of the World' (1981) and 'The Real Life of

Alejandro Mayta' (1984) were shaped by it. In 1986 Vargas Llosa turned

his hand to detective fiction and wrote the fast-paced cops and killer

thriller ' Who Killed Palomino Molera' . Although the novel lacked the

thickly layered narrative scope of his other works, it clearly proved

the author's talents for writing sordid detail and earthy, comic

dialogue.

His 1987 work 'The Storyteller' returned again to the theme of

tale-telling from multiple points of view. It relates the adventures of

a nameless narrator who is fascinated by the almost mystical

transformation of his college friend, Saul Zurantas, a Peruvian Jew and

former student of ethnology, who leaves civilization to live and tell

tales among the Machiguenga tribesmen in the depths of the Amazonian

rain forests. "Who is purer or happier because he's renounced his

destiny?"

The storyteller asks as he roams the jungle with the Machiguenga,

people who must continually walk in order to fulfil their obligation to

the gods and preserve the earth and the sky and the stars. "Nobody," the

storyteller responds. "We'd best be what we are. The one who gives up

fulfilling his own obligation so as to fulfill that of another will lose

his soul."

A haunting, deeply spiritual novel, 'The Storyteller' is entirely

different in scope and tone from Vargas Llosa's later work 'Elogio de la

Madrastra' (1988), an erotic tale of sexual tension between a stepmother

and stepson, described by the author as a "diversion." An English

version, which translates 'In Praise of the Stepmother', was published

in 1990.

It was an erotic novel about a beautiful but naughty little boy. The

later novels are amazing works from a man who temporarily abandoned his

isolation as a writer to pursue an active political career. This was to

fulfill what he considered his obligations toward improving the moral,

social and economic quality of life in his country.

In 1990 Vargas Llosa became the candidate for president of a

centre-right coalition called the Democratic Front (Fredemo). He was

opposed by the candidate of the Change (Cambio) 90 Party, Alberto

Fujimori. The well-known author took an early lead but gradually lost

ground and in a run-off election was defeated by Fujimori. His book

about the experience, 'Tale of a Sacrifical Llama', released in June,

1994, offers a convincing self-portrait of a political innocent sinking

under a tide of democratic absurdities. This follows his work 'A Fish in

the Water: A Memoir' which detailed "his bittersweet look at the nearly

three years he spent in public life."

Vargas Llosa went back to his writing full-time after his brief

affair with politics. The coveted Planeta Prize for 1994, traditionally

awarded each year to a Spaniard for the best pseudonymous submitted

manuscript of fiction, went to Mario Vargas Llosa (whose application for

Spanish citizenship was approved in July).

His 'Lituma en los Andes' (translated as Death in the Andes) is a

story of political violence and social regression within a contemporary

Andean setting. His 1997 novel, 'The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto' marked

the first time any publisher had released a title in all

Spanish-language markets on the same day. Sixteen of the 26 countries

involved (including Spain) have Santillana companies to print and

publish.

In the case of 'The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto', only Spain and

Mexico printed for all the others. In the first month of publication

250,000 copies were sold, 100,000 of them in Latin America.

"I am very surprised, I did not expect this," the author told Spanish

National Radio last week. "I am very surprised, I did not expect this," the author told Spanish

National Radio last week.

He said that he thought it was a joke when he received the call

informing him that he won the Nobel Prize. "It had been years since my

name was even mentioned," he added.

"It has certainly been a total surprise, a very pleasant surprise,

but a surprise nonetheless."

He is South America's first laureate since Colombia's Gabriel García

Márquez won in 1982. Once close friends, the two men have been involved

in a ongoing feud since a punch-up in a Mexican cinema in 1976.

The academy's permanent secretary, Peter Englund, called the Peruvian

a divinely gifted storyteller and worthy winner of the 10 million

Swedish Kronor prize (168,971,851.62 LKR). For years many predicted that

the author would add the Nobel to his Cervantes prize but Llosa himself

said his liberalism (which he defined as defending democracy and the

free market) meant it was "completely impossible" for him to win.

"I have taken all the precautions necessary for them never to give it

to me," he joked last year.

|