Politics of memory: conceptions and perceptions on the 'past' and

'history'

By Dilshan BOANGE

Part 2

Continuing from the previous week's article of what conceptions can

be analysed of Milan Kundera's The Book of Laughter and Forgetting on

memories of the 'past' and 'history', the discussion now looks at

aspects such as 'individual memory' and 'collective memory' and also the

concept of 'official memory' which takes highly political dimensions.

British novelist and short story writer L.P Hartley's words "The past is

a foreign country" seems to resonate how the past can be viewed as 'a

place' which man possibly yearns for, but has become estranged from him

as a result of not being part of his material/physical present. But 'the

past' is activated to the present through memory, as Elizabeth Jelin

points out, and therefore the space which we conceive as 'the past' can

be understood as a space of memory.

|

|

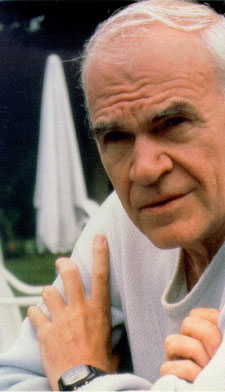

Milan Kundera |

'Individual memory', 'Collective memory' and 'Official memory'

In discussing politics of memory the idea of 'individual memory' and

'collective memory' should be looked at for the differing dynamics and

potentials they may possess. The idea of collective memory as discussed

by Jelin gives different perspectives on the matter.

"...[T]he collective aspect of memory is the interweaving of

traditions and individual memories in dialogue with others and in a

state of constant flux"

While a certain social element or basis is brought in to play in the

above extract in grounding 'collective memory' Jelin's cites the views

of French philosopher Paul Ricoeur in her academic article to trace

attributes/features that are incorporated in history as being a basis on

which 'collective memory' can be understood. Following is an excerpt of

what Jelin has cited of Ricoeur.

"[C]ollective memory simply consists of the set of traces left by

events that have shaped the course of history of those social groups

that, in later times, have the capacity to stage these shared

recollections through holidays, rituals, and public celebrations."

In this respect one could argue that memory is a basis on which

history is built. And it is interesting to note how the idea of history

construction through affecting memory is indicated in the very opening

of 'The Book of laughter and Forgetting,' by presenting what the author

expresses as a landmark event in the history of Prague. This very

section is discussed in Jelin's article in relation to voids/gaps in

memory which take on the facet of representing 'the absent' or the

oblivion as Jelin calls it. Following is an extract from The Book of

Laughter and Forgetting which demonstrates how the idea of how

propaganda machinery of a regime first perpetuates memory through

historicizing an incident. -

"In February 1948, the Communist leader Klement Gottwald stepped out

on the balcony of a Baroque palace in Prague to harangue hundreds of

thousands of citizens massed in Old Town Square. That was a great

turning point in the history of Bohemia...Gottwald was flanked by his

comrades, with Clementis standing close to him. It was snowing and cold,

and Gottwald was bareheaded. Bursting with solicitude, Clementis took

off his fur hat and set it on Gottwald's head

The propaganda section made hundreds of thousands of copies of the

photograph taken on the balcony where Gottwald, in a fur hat surrounded

by his comrades, spoke to the people. On that balcony the history of

Communist Bohemia began. Every child knew that photograph, from seeing

it on posters and in schoolbooks and museums." (P.3)

The fact that the 'propaganda section' made the photograph almost a

site to mark an event which Kundera marks as the initiation point of

communist Bohemia, shows how a state agency can create 'documents of

history.' And this 'document' becoming commonly known as a marker of

history, contributes to the citizenry's memories of this event. Though

witnessed it as individuals they would each hold a similar memory

verified by a corroborative 'document' which can be interwoven into each

individual to create a 'collective memory.' Yet one could argue whether

the individuals who carry a memory of the event by virtue of seeing a

photograph of that event would in fact have an experience of having

'lived it' personally. Here once again one can observe how (mass) media

methods come into play. It is very much the media that dictates to the

masses of what can be made memory worthy and what is forgettable.

Subsequently Kundera shows how documents of history devised by the state

authorities can be manipulated to suit political ends. And thereby

'official memory' is manipulated to rewrite the past. In the following

extract Kundera demonstrates how 'absence' can be created and made to

serve political ends.

Four years later, Clementis was charged with treason and hanged. The

propaganda section immediately made him vanish from history and of

course, from all photographs. Ever since, Gottwald has been alone on the

balcony. Where Clementis stood, there is only the bare palace wall.

(P.3-4)

The disappearance of Clementis from the photograph shows how

political machinery would act to manipulate documents of history, and

reinterpret events which are sought to be reshaped as official memory.

In such a case history would obviously be rewritten and official memory

can alter to suit the 'historicity' which suits the historian.

Therefore, an absence can be political.

Referring once again to Kundera's words on the character of

Mirek-"Mirek rewrote history just like the communist party, like all

political parties..."(p.30) History is apt to be written and rewritten

in the will of an authority. And 'the past' it appears is a space that

needs to be controlled for the formulation of history.

Memory entrepreneurs

In the academic essay "Political struggles for Memory" Jelin speaks

of 'memory entrepreneurs', who are rebels of sorts against the regime

and carry on a struggle over memories presenting interpretations and

narratives of their own of the past. These individuals may be seen as

creating 'alterity' to the established narratives of history and

official memory of the past. Is Kundera's novel an act of memory

entrepreneurship? Jelin in her essay says of the nature and motive of

the memory entrepreneur-

"We will also find them engaged and concerned with maintaining and

promoting active and visible social and political attention on their

enterprise."

Taking in to consideration what is said in the above extract, once

again the question can be asked -is Kundera a memory entrepreneur?

The fact that Kundera in his novel delivers a voice against communism

posits his novel as a work which calls attention to a narrative outside

the master narrative of the state. And through his analysis of what

state machinations are found in the production of documents of history

that reinterpret 'the past,' Kundera seems to be critical of the

regime's politics over memory and history writing, while subtly

indicating a conscious effort or enterprise of his own to challenge the

authenticity and the authority of the history constructed by the

Communist party in Prague.

If Kundera can be viewed as a memory entrepreneur who has presented a

narrative of the past which seeks to preserve certain memories that are

sought to be controlled, such as the photograph of Klement Gottwald from

which Clementis was made to disappear, then is it possible that The Book

of Laughter and forgetting is a vessel in which memory seems to be

preserved? Thereby making the novel a document of history that is

outside the official space?

Jelin's article with its scholarly analysis appears to lend an

understanding about the matter by stating-

"Memory, then, is produced whenever and wherever there are subjects

who share a culture, social agents who try to "materialize" the meanings

of the past in different cultural products that are conceived as, or can

be converted into, "vehicles for memory" such as books, museums,

monuments, films, and history books."

This perspective of Jelin's may allow Kundera's novel to be viewed as

a cultural product produced by a social agent that attempts to

materialize the past (and the memory in which it lies) in a text that

may serve as a vehicle to carry 'memory.' The politics of the historian

can be aligned with the needs of those who would in the words of Kundera

"want to be masters of the future only for the power to change the

past." And historicity would seem to lie in memory that is private and

official, individual and collective. The discussion of this article

looked at how memory would constitute 'the past' and what politics

become attached to such spaces.

Manipulation of 'the past' or its control would be accomplished by

distorting spaces of memory, and remembrance, such as the photograph of

Klement Gottwald in Kundera's novel. Thus collective memory could be

manipulated to suit the political necessity of a regime that would

through the device of history control 'the past.' And if indeed one were

to evoke once again the words of L.P Hartley -"The past is a foreign

country" then no doubt any who designs mastership over territories must

view the past as a land that needs to be conquered.

|