|

Poetry and the theme of loss

Reviewed by Prof. Wimal Dissanayake

Where else am I walking even now Looking

for me - W.S.Merwin

‘Sunshine and Shadows’ is Kamani Jayasekera’s second collection of

poetry in English, the first being ‘Petals in the Wind.’. This new

volume of poems, consisting of over fifty poems, represents an advance

over her work in terms of content, language and representational

strategies. Her poems deal with largely personal experiences,

observations, reflections, at times interwoven with social observations.

These poems, which are pages from her lived world, also contain a spine

of social commentary, that serve to underline the dangers of spiritual

stasis and moral entropy. Many of her poems the traverse the distance

between desire and despair, possibility and fulfilment, individual

yearnings and social imperatives, sound of tradition and call of

modernity. The complex negotiations involved in this commute only serves

to draw attention to the dramatic divergences between these polarities.

The theme of loss is central to Kamani Jayasekera’s poetry - loss of

desire, loss of trust, loss of faith, loss of conviction and the loss of

language. This theme of loss emerges as a connective thread running

through the poems and investing them with a recognizable unity. It can

be described as the activating and organizing topos in her poetry. It is

not always easy to explore the theme of loss without falling into

sentimentality, self-pity, bathos, and even morbidity, - failings that

have disfigured the writings of some of the greatest poets. It is to

Kamani’s credit that she has, for the most part, succeeded in avoiding

these tempting pitfalls. The theme of loss is central to Kamani Jayasekera’s poetry - loss of

desire, loss of trust, loss of faith, loss of conviction and the loss of

language. This theme of loss emerges as a connective thread running

through the poems and investing them with a recognizable unity. It can

be described as the activating and organizing topos in her poetry. It is

not always easy to explore the theme of loss without falling into

sentimentality, self-pity, bathos, and even morbidity, - failings that

have disfigured the writings of some of the greatest poets. It is to

Kamani’s credit that she has, for the most part, succeeded in avoiding

these tempting pitfalls.

Many of the poems deal with the poet’s relation to objects, places,

people, and landscapes, and in poems of this nature, the centre of

gravity almost always shifts to the subject . However, Kamani has sought

to maintain a nice balance between the poetic subject and poetic object

thereby foregrounding the attachments, affiliations, and interaction.

These attachments, affiliations and interactions themselves, very often,

end with the anxieties and raptures of newer realizations and

unanticipated recognitions. It is through this means that Kamani seeks

to attain the wisdom that the eminent American poet, Robert Frost,

thought was the destination of poetry.

As I stated earlier, Kamani’s poems, by and large, are personal,

gentle, compassionate; they almost carry the gentleness of their

conviction. However, within their autobiographical trajectories, are

embedded engagements, never in a high-handed way, with social, moral,

ethical issues. This move has the effect of investing her poems with

another layer of significance. The impulse for this engagement grows of

her visible desire to braid private necessity with public conviction. At

times, this tends to generate, to my mind, a wholly understandable

tensions growing out of alienations and dislocations in new emotional

and cognitive spaces.

Kamani Jayasekera’s intention has been to map diverse emotional

terrains with precision, wit and discernment. Her preferred mode of

approach has been to aim for compactness and compression – to strip

language to its bare essentials. Her style is unmannered and

unembellished and often colloquial. This makes her language simple, but,

in many instances, there is richness to that simplicity. Her poems, with

their interplay of certainties and uncertainties of meaning, gesture

towards a pregnant silence that inhabits a space beyond language. Her

desire to venture into linguistic and cultural silences marks her best

poems. She is keen to tap into a layer below words in order to reach a

space beyond words. And her compositions are not unduly weighed down by

rhetoric, a fact that lends greater force to this desire.

Let me illustrate my conviction with a few examples. The poem

'Parents' consists of four lines

When living, I had little time

To spend with you.

In death you live

Eternally by my side.

Here, a whole world of deeply felt emotion is compressed into four

lines, and the matter-of-factness of the statement adds to the poignancy

of the situation. The poem titled the 'Ruins', Kamani captures a tragic

scene with the above stated cultural silence surrounding the poem,

despite the unevenness of statement.

Wounded by missiles

Dried up by the beating sun

Washed over in rainy seasons

An empty shell of a temple remains

In no mans land in solitude

Where have the gods gone?

Where have they fled to?

Destroyed by both enemy and friend

Caught between cross fire

Ruined by the same people no doubt

Who fall at their feet

Seeking favours

At a better time in a better place

Many of Kamani Jayasekera’s poems are short; however, they could be

shorter. I was reminded of a comment made by a critic on the poetry of

the distinguished American poet, Robert Creeley. ‘There are two things

to be said about Creeley’s poems: they are short; they are not short

enough.’

Kamani Jayasekera’s poems display the activating power of a

triangular relationship – the local experiences and concomitant modes of

sensibility, the English language and the intertextualities provided by

classical Greek and Roman cultures. This triangular intersection gives

some of the poems a reverberative power. The idea that life is in

incessant flux, that one does not step into the same river twice, is

central to the thought of Heraclitus as indeed it is for Buddhist

thinking. What is interesting about KamaniJayasekera’s poems is that she

is seeking in this Heraclitian flux a point of stable order, a graspable

pattern; at a deeper level of imaginative apprehension, this is indeed a

desideratum that Heraclitus had in mind too. That human beings are

perceived to be in a permanent state of exile makes this ambition all

the more compelling.

As I suggested earlier, Kamani abhors excess, ornamentation,

heightened self-display preferring a mode of measured statement driven

by restraint. Her bent is in the direction of understatement. There is

no attempt at overt moralizing or loading the dice. She also avoids

excessive focus on aesthetics as that can easily lead to a malady of

imagination. Her poems are sustained by a conviction that exuberance of

enactment often undercuts the essence of that very effort. She shows

little interest in reaching out to spaces that lie beyond one’s grasp,

recognizing full well the fact that the spaces within once grasp are

complex and many-sided enough. She hums around the edges of

autobiography without making an orgy of self-exhibitionism. Her thematic

interests and stylists propensities are united in her privileging of

understatement; she realizes that sometimes less can be more.

As with all collections of poetry, including those of the finest, not

all poems gathered in this volume are equally strong. Some appear to be

sketches that could attain their full height in later incarnations; some

invite metaphorical intervention to relieve them of their prosiness,

while others seek architectonic refurbishing. Rhythmically speaking,

some could gain by a more vigorous athleticism. A close friend of mine,

the eminent American poet Reuel Denney, in a conversation that took

place many years ago, told me that fancy footwork in poetry should not

be abandonment, but rather an enlargement, of the virtues of prose. I

still think it is a useful piece of advice. Gertrude Stein once

proclaimed, ‘Remarks are not literature.’ This is again an admonition

well worth adhering to. We as writers often fall short of the mark we

set for ourselves; how we long to chisel that perfect poem! How we seek

to promote the ideal union between language and emotion! I recommend

Kamani Jayasekera’s new collection of poems, interesting as it is, not

so much for its achieved art as for its promise, its display of

possibilities for future growth.

Avarjana:

Voyage into the turbulent life

Reviewed by Ranga Chandrarathne

Avarjana, a novel by Srimathi R. Weerasuriya portrays life and times

of an era through personal memoirs of Sitara, a pivotal character and

the narrator of the novel. The story is linked with the fate of Sitara

who has to live with a rich aristocratic family foregoing many

opportunities in life and keeping some family secrets of Ravinatha’s

family.

The story of the novel revolves around the life of Sitara who lost

her parents and has to live with her paternal uncle until he died in a

vehicular accident. Sitara’s kind uncle and aunt have to take into

custody Chamara, a child born out of wedlock while Chamara’s young

mother leaves back for Middle east for employment. The narration moves

on as Chamara is adopted by rich aristocratic couple, Ravinatha and

Uthpala who have no children.

The large part of the novel is in the form of Sitara’s reminiscences.

She narrates how she has to spend the life with Ravinatha family because

of Chamara. The large part of the novel is in the form of Sitara’s reminiscences.

She narrates how she has to spend the life with Ravinatha family because

of Chamara.

“As the darkness gathers, the electric lights of the fleet of

vehicles, plying along the distant road fall on men and women walking on

the road making their silhouettes clearer. For a moment, night would

arrive and then a day would dawn and another evening would pass by in

the same manner. I am reaching seventeen and how many such evenings

could I experience? A breeze brings about a chill to the body. I stepped

back into the house. At the far end of the garden, the graves of

Ravinatha as well as his family members were seen through the darkness.

They shone white as light from a lamp post cast on them. Chamara takes

the trouble to keep graves clean. What does he know of his ancestry?

Isn’t what he knows an illusion? He is an outsider to the family. He

believes that it is his duty to preserve the traditions that were handed

down from generation to generation. He respects convention. I could see

Keerthi Hamu engaged in a task under the cluster lamp in the living

room. I could recall how Chamara came home on his mother’s hands as a

lovely baby and uncle Nimal, aunty Kumari, Nilu and I looked at him with

love. What I know of him would die with me. He would leave this earth

with things he did not know….”

With the above moving passage, the author concludes the novel which

at a superficial level is a family saga. However, the author touches on

many themes while utilising nostalgia as a mode of narration. Poverty is

one of the themes that the author tries to develop through the

narration.

The major incidents in the novel such as the principal character of

the novel Sitara has to live with her paternal uncle and aunty,

Chamara’s biological mother has to leave him in the custody of Sitara’s

adopted family, adoption of Chamara by Ravinatha and Uthpala and Nilu’s

early marriage and leaving the country are more or less linked with

poverty. Through the lengthy descriptions of the aristocratic family of

Ravinatha and poverty- stricken Sitara’s family, the author has

attempted to portray diverse social strata in contemporary Sri Lankan

society. Though briefly described, Charmara’s mother represents Sri

Lankan migrant workers and the socio-cultural issues they face at places

of work in the Middle East.

Although the author has used colloquial Sinhalese idiom for the

narration, it has been used in such a manner grabbing the reader's’

attention throughout the novel. The author has used simple diction which

is appropriate for the narration. Dialogues have been used sparingly.

Except for the rapid sequence of tragic incidents which are at times

incredible, the author has developed the plot convincingly. Characters

have also been evolved in a logical manner in general and Sitara’s

character in particular.

The author has used Ravinatha’s diary entries to highlight the tragic

part of his life after the death of Uthpala due to cancer. Ravinatha led

a lonely life. The author vividly captures the personal tragedy that

befell Ravinatha through his diary entries as they were read by Sitara.

“…After Uthpala left me I had not thought of another woman. I

declined the marriage proposals made by my friends as I was quite unable

even to think of a marriage. My world was Chamara who Uthpala and I

adopted. The girl who was to bring him up became extremely helpful to

me. How nice if that girl be intimate with me? It would also be

beneficial for the child. I saw her at her home as a young girl. Have I

thought that she would ever be my wife? Some happenings in life are

astonishing. As Victor told me she has no reason to oppose this

proposal. I should explain her that the age gap would not be an issue. “

The central theme of the novel is nostalgia. The author has exploited

the theme at different levels. At one level, she has used nostalgia as a

mode of narration. The plot unfolds from the perspective of the

principal character Sitara, her early life and evolution of her into a

spinster and her recollections of the past and future. At the end Sitara

reconciles with her plight in retrospect of the life she could have

spent if she did not make sacrifices for the sake of the child, Chamara.

“None of my relations involved in these episodes is no more. Those

who surround me today are not my blood relations. They are all

strangers. But they all love me a lot. …my teacher parents with a

considerable fortune had not dreamt that their only daughter would live

among strangers. But I lead a contended life.

I have no repentance. From my friends as well as from Nilumi’s point

of view, I am leading a failed life. Nilumi is a grandma surrounded by

grandchildren. My longstanding friend Pujani, who has been keeping in

touch with me for a long time, now lives with her husband and children

in London….”

In the evening of her life, Sitara looks back on her childhood and

youth. Through the character of Sitara, the author offers a philosophy

of life which is different from the aspirations of an ordinary woman. 'Avarjana'

would be a novel experience for Sinhalese readership.

A fresh approach to portray Australian migrants and Aborigines

Reviewed by Prof. Santosh Sareen

Sunil Govinnage’s poetry explores the relationships between place and

identity, memory and desire. As a mature poet and an immigrant to

Australia, he is capable of seeing things which are not usually captured

by Australian poets who grew up in the former convict colony.

White Mask is Govinnage’s first collection of poetry. He selects a

wide variety of themes such as place, identity, love and despair as his

subject matter. He also writes about natural justice, human values, and

environment. Readers will find new imagery and fresh approaches,

particularly in the way Govinnage has portrayed Australian migrants and

Aborigines in his poetry.

One of the most remarkable features of Sunil Govinnage’s poetry is

his strong desire to discover new values and explore other

interpretations of the Australian continent, its First Nation —

Aborigines —and the new settlers: migrants, both black and white, who

have arrived in the country since white colonisation. One of the most remarkable features of Sunil Govinnage’s poetry is

his strong desire to discover new values and explore other

interpretations of the Australian continent, its First Nation —

Aborigines —and the new settlers: migrants, both black and white, who

have arrived in the country since white colonisation.

Separation, in one form or another, is the conceptual builder of the

poems in this anthology. The poem entitled ‘A White Memory’, for

instance, carries a note of nostalgia for what was or has been. The

dominant case, the k?raka, of this poem is the ablative case, the

ap?d?na representing the case of separation and sorrow. The foreground

images are the memories of a lost land, a lost happiness, and a never

forgotten memory. In White Mask the poet is nostalgic for the rich

culture he has left behind in his country of birth, Sri Lanka.

‘I Don’t Write Poems in Sinhala Any More’ is another pivotal poem in

this collection. Notwithstanding the poem’s title, there is a note of

hope in this poem. In the poetry of the region, and very much so in

Govinnage’s poetry, there is an undercurrent of transcendental

resolution, renewal, a hope of meeting the past, a rebirth or a

perpetual unity that is not shattered by temporal facts of birth and

death.

There is a complex structure of emotional and intellectual experience

in Govinnage’s poetry. He uses powerful images captured from nature, and

from human and other person-made objects.

These images, their meanings and sensibilities bear the imprint of

the tropics; the images correspond to nature and to the traditions and

the values of the people.

In Govinnage’s poetry, we find not only a nostalgic presence of a

rich culture but the ability to recollect and narrate an interesting

interplay between home and exile. Govinnage has great mastery over the

English language and deftly handles images and other poetic devices.

In summation, the strength of Govinnage’s poetry lies in his ability

to investigate and provide new insights into matters that others take

for granted. He is also gifted in his native tongue — Sinhala — which

has a literary history of over 2,500 years. Therefore, he can easily

draw from a rich culture and the language in which he first wrote

poetry.

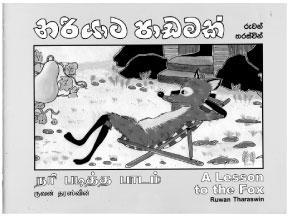

Nariyata Padamak

Ruwan Tharaswin’s latest book Nariyata Padamak carries a popular folk

tale of Sri Lanka in all three languages.

The story and the illustrations are by Ruwan Tharaswin. The English

translation is by Malini Govinnage. The story has been translated into

Tamil by Arul Sathyanathan. The book is printed by ANCL Commercial

Printing Department. It is an author publication available at leading

bookshops.

New arrivals

Veera Daruva

Prabhani Rodrigo’s Veera Daruva is a children’s story book based on a

North American folk tale. The book is illustrated with colour sketches

drawn by Gamini Abeykoon.

Veera Daruva is an Asiri publication.

Lakdiva Buddha Prathimava

Malinga Amarasinghe’s “Lakdiva Buddha Prathimava” will be launched at

Dayawansa Jayakody Bookshop, Ven. S. Mahinda Mawatha, Colombo 10 on

October 19 at 10 a.m.

The author is a senior lecturer in Archaeology at the university of

Kelaniya.

This is a Dayawansa Jayakody publication. |