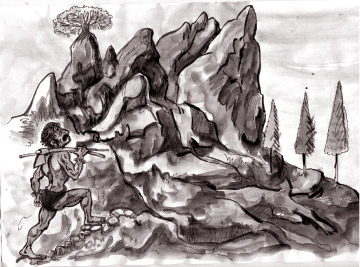

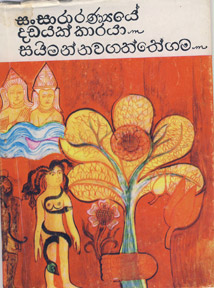

Sansaaraaranyaye Dadayakkaraya

(The hunter in the wilderness of Samsara)

An introduction

|

|

Simon Navagaththegama |

From this week on, Montage will serialise

the English translation of Simon Navagaththegama's 'Sansaaraaranyaye

Dadayakkaraya' (The hunter in the wilderness of Samsara) by Malinda

Seneviratne. Malinda is a bilingual who has been writing on different

topics to mainstream English newspapers and popular columnist. He is

also a poet, writer and translator. He has translated Martin

Wickremasinghe's autobiography Upandasita into English.

By Ranga CHANDRARATHNE

'Sansaaraaranyaye Dadayakkaraya' (The hunter in the wilderness of

Samsara) is considered as an important modern Sinhalese literary

production which deals primarily with the Buddhist concept of Samsara or

Sansara in Sinhalese. Author Simon Navagaththegama's contribution to

contemporary literature is monumental. At a rudimentary level,

Navagaththegama has introduced new tropes to the Sinhalese contemporary

novel taking it out of the realistic mood, the dominant genre of the

Sinhalese novel in the 1960s. In that sense, Navagaththegama marks a

seminal trajectory in Sinhalese novel. The themes that he deals with are

often radical in the sense that they are on the periphery of

conventional morality; for instance, his Suddilage Kathawa is quite

unconventional and deals primarily with the dynamics of sex life in a

traditional village which is in contrast to the idyllic fictional

village portrayed by Martin Wickremasinghe in his literary productions.

In this brief introduction to the translation, I wish to deal with

the central theme of the novel, the Buddhist concept of Samsara or

Sansara in Sinhalese. The entire novel is set against the conceptual

frame work of Samsara and the principal characters such as Dadayakkaraya

or the hunter has been used to navigate the different layers of the

novel.

The Buddhist concept of Samsara or Sansara

The central theme of the novel is the Buddhist concept of Samsara. It

is one of the most complex Buddhist concepts. Samsara or transmigration

as it is called in some schools of Buddhism is found in most Indian

philosophical traditions. Even in orthodox Hindu and heterodox Buddhist

and Jain philosophical traditions, an ongoing cycle of birth, death and

rebirth is considered as a fact of nature.

It is believed that the law of Samsara, everything is said to be in a

cycle of birth, death and rebirth. The Buddhism teaches that there is no

individual soul and that the existence of individual self or ego is an

illusion. What transfers from one existence to another is only a

collection of feelings, impressions and that the individual in the

present life will not be the same in the next life but be an individual

with similar characteristics. It is believed that the law of Samsara, everything is said to be in a

cycle of birth, death and rebirth. The Buddhism teaches that there is no

individual soul and that the existence of individual self or ego is an

illusion. What transfers from one existence to another is only a

collection of feelings, impressions and that the individual in the

present life will not be the same in the next life but be an individual

with similar characteristics.

According to core belief of Buddhism, all living beings are born into

one of the six states of existence. Etymologically, the word Samsara in

Sanskrit means the cycle of life and death. Tibetan Buddhism calls it a

wheel of life in which all beings are trapped. It is believed that all

beings trapped within the six realms are subjected to death and rebirth

in a recurring cycle of Samsara over incalculable ages until they reach

enlightenment.

In the novel, the hunter, first known as Golu Puncha and then as

Davantaya, is directly linked to Samsara. From the very birth, he is

destined to serve the lonely monk living in a dense jungle. The monk has

been waiting for him for over centuries and the hunter with a strong

physique is led into the forest by a deity. The entire existence of the

hunter seems to have been pre-destined.

At different stages of the narration, it has been suggested that the

hunter had played the same role in his previous existences. In one

instance, when the monk offered the forest and its treasures to the

hunter, the Bahiravaya or the guardian spirit of the treasures

accompanied by the guardian cobra, show the hunter his treasures. The

treasures are buried in a pit and through the stone fleet of steps, the

hunter walks down passing seven layers of civilizations in which he

feels intuitively that he has played the same role as a hunter carrying

an axe. In fact, faintly he recognises a huge -ape like Skelton in one

of the civilizations he passes through as that of him in the past

existence.

"The Hamuduruwo waited for him. The Hamuduruwo had all the time in

the world to wait for the hunter. For these two who lived in the jungle,

time was neither short not long. The Hamuduruwo watched the hunter who

had been walking up to him and was now staring at the nest. " - Malinda

Seneviratne

The time is one of the recurrent themes of the novel. For both the

monk and the hunter, concept of time is something alien. The monk waited

for his companion to meet him up for centuries. They meet at the

monastery of Samsara. Although the title suggests a monastery, in fact,

there is no monastery. At a superficial level, it is the forest and its

confines which make up the 'monastery'. At another level, it is the

entire cycle of birth, death and reincarnation which is referred to as

Sansara Arannayaye or monastery of Samsara. The time is one of the recurrent themes of the novel. For both the

monk and the hunter, concept of time is something alien. The monk waited

for his companion to meet him up for centuries. They meet at the

monastery of Samsara. Although the title suggests a monastery, in fact,

there is no monastery. At a superficial level, it is the forest and its

confines which make up the 'monastery'. At another level, it is the

entire cycle of birth, death and reincarnation which is referred to as

Sansara Arannayaye or monastery of Samsara.

Post modernist aspects

One of the prominent features of the novel is its post modernist

aspect. Like in his many of works such as Shapkshani, Navagaththegama

deals with many post modernist themes such as diverse aspects of

sexuality. For instance, when a virgin was to be sacrificed to get the

treasure, the hunter looked at her curiously as she was naked. Although

sex is not a dominant theme of the novel, it has been exploited in many

instances.

" The hunter was hypnotized by the beautiful and small hooded head of

the Naga Manavikava. He deliberately avoided looking at the Naga King.

He didn't look at the splendid and handsome creature almost as though

such a glance would evoke in him a jealous hatred. The Naga Manavikava

unfolded her hood and began swaying to and fro in the manner of

beginning a dance. His peripheral vision caught sight of the Naga King

slithering towards her. At the same time the snake that had been still

and quite within him began to come to life and uncoil. It too struggled

with the desire to proceed towards the Naga Manavikava. And yet the

hunter stood his ground like an enormous tree that had sunk deep into

the soil its roots. All he did was to spread his legs just enough for

the Naga Manavikava to be able to see the slow dance of his snake. The

Naga King who protected the treasure was not by her side, hood touching

hood, bodies entwined in slow dance. If the hunter so wished, his Naga

Raja would in an instant be grappling with the Naga King in deadly

battle. "-Malinda Seviratne

Here the hatred that would evoke in the Hunter is a sexual

connotation. The above scene can be read in different lights. One may

say that it is a manifestation of suppressed sexual desires of the

hunter. In terms of narration, the novel is not unified. There are some

instances where a disturbed state of mind of the hunter is represented

in terms of descriptions. Even the mind is described. At one point the

monk could not concentrate his mind and could hardly meditate. He asked

the hunter to keep vigil over the night. At night the monk's worldly

desires manifested in the form of a beautiful maiden feeling his face.

The author skilfully depicted that it was only an illusion when the

maiden was reduced into an ant. The hunter killed the ant and showed it

to the monk. In the same night, the monk attained enlightenment. Cobra

and maiden are potent sex symbols at a different level.

Seminal trajectory

The novel Sansaaraaranyaye Dadayakkaraya' is also an important

trajectory in contemporary Sinhalese novel in terms of diction and

narration. Although it seems that the author use simple diction with

minimal use of metaphors, the narration yields several layers of

meanings and set against the complex Buddhist concept of Samsara. It is

psychological in outlook given the fact that the author depicts the

states of minds of both the monk and the hunter.

The hunter is depicted as a dim-witted person with a huge physique

and is pre-destined to serve the monk. The monk is practising meditation

to achieve enlightenment. At one level, it seems that the monk's mind is

represented by peripheral characters such as the guardian deity living

in the Asatu tree, Bahiravaya or the guardian spirits of treasures,

cobra and the hunter.

In general, the language is matter of fact. However, there are

descriptions in the narration which are more or less reflections of the

mid sets of the hunter, lased with meanings.

The vast forest, in which the monk and all the dramatic personae

live, metaphorically represents the vast expanse of time over

millenniums. In fact, the forest is an important character of the novel.

The novel is complex and yields myriads of meanings. We hope that the

authentic translation would also capture the vividly realised narration

in the original and that readers would enjoy it.

Translator's Note

I first read the novel in

1998, when I was a student at Cornell University, NY. That

semester I took a class with Geoffrey Waite of the German

Studies Department. It was titled 'Marx, Nietzsche and

Freud'. As graduate students, we were required to maintain a

journal, commenting on the lecture and assigned literature.

While jotting down my weekly journal entry I realized that a

passage from Simon Navagaththegama's 'Sansaaraaranyaye

Dadayakkaraya' captured in pithy terms the point I was

trying to make. Geoff didn't know Sinhala. I translated the

paragraph. It was a pleasurable exercise and I thought I

would try my hand at translating the entire book. I first read the novel in

1998, when I was a student at Cornell University, NY. That

semester I took a class with Geoffrey Waite of the German

Studies Department. It was titled 'Marx, Nietzsche and

Freud'. As graduate students, we were required to maintain a

journal, commenting on the lecture and assigned literature.

While jotting down my weekly journal entry I realized that a

passage from Simon Navagaththegama's 'Sansaaraaranyaye

Dadayakkaraya' captured in pithy terms the point I was

trying to make. Geoff didn't know Sinhala. I translated the

paragraph. It was a pleasurable exercise and I thought I

would try my hand at translating the entire book.

It was tough throughout.

Simon's lines have several layers of meaning and I found

that I would be lucky to get more than one of these down in

English. More often than not I would end up adding my own

'layer'. It was, as one would expect, a transliteration. I

translated 2 chapters and emailed them to my friend Liyanage

Amarakeerthi who at the time was reading for his doctorate

at the University of Wisconsin (Madison). He strongly

encouraged me to complete the translation. I did.

Upon returning to Sri Lanka

in 2000, I gave the manuscript to the author, along with a

soft copy. He liked it and urged me to publish it. I said it

needed to be 'cleaned up'. Time passed. Simon lost the only

soft copy I had and more than half the manuscript. He

returned what was left and I duly lost it too. I will always

regret the fact that he will not see this.

This re-transliteration

comes more than a decade after the first attempt. It will be

different, I know. Hopefully it would do more justice to the

original than the first. |

|