Sansaaraaranyaye Dadayakkaraya

(Chapter 1)

(The hunter in the wilderness of sansara)

By Simon Navagaththegama

Translated by Malinda Seneviratne

Part 2

Up to this point, everything was done by the hunter. All that the

Hamuduruwo did was to observe. And yet it was as though they both

partook of some perfectly ordinary morning exercise. The hunter engaged

in a certain hunting expedition early in the morning. The wise

Hamuduruwo, in accordance to the customs of his asceticism, participated

fully and as appropriate in a morning’s sport. It appeared as though it

tired him, but only on account of age. The hunter ascertained through

the morning sunrays that the ancient life-signatures that marked the

Hamuduruwo’s face had been washed in heavy perspiration.

|

|

Simon Navagaththegama |

The Hamuduruwo looked at the hunter and turned his gaze upon the

brine marked horizon. Many miles away a wisp of smoke pierced the mist

and made its solitary way into the sky. It may have been the residual

mark of a chena that had been set fire to the previous day.

As the reverend’s thoughts traversed the horizon, they were overtaken

by a faint trace of sadness as well as compassion. Perhaps into those

compassionate thoughts had strayed a tinge of pity for himself, all

mankind and the hunter.

His thoughts went to his teacher, Gauthama the Buddha, who lived many

centuries before. The Lord had arahats who could share with him the

splendour of a beautiful morning even in a lonely world laden with

sadness just like this.

As the Lord, having woken up early, paces in meditation, Arahat

Kashyapa the Great comes towards the Exalted One. To Lord Buddha’s eyes

are gifted the calm face of Arahat Kashyapa, as clear as an autumn sky

upon which the full moon has spread itself.

‘O Kashyapa, did you spend the night in pleasant slumber? Did you

suffer any discomfort?’

It is not necessary to respond in word. In their eyes reside both

question and answer. Nevertheless arahats and Samma Sambuddhas just like

any of us see worth in the conventions related to the courtesies of

pleasant conversation. And thus the Reverand Kashyapa indulgences in

convention.

‘Yes, Lord, I slept well indeed. I believe you too, Lord, spent a

night of pleasant slumber.’

The Hamuduruwo looked upon his abiththaya with a sense of self-pity.

This giant of seven feet with a body of an elephant, this pruthagjana,

in comparison with the vast spaces that surrounded them, was indeed a

tiny man. The hunter was looking with a sense of curiosity. Although the

Hamuduruwo’s mind enveloped the heavens, extended to the far away sea

and traveled through the past, present and future he was not privy to

its inner chambers. He only noticed the Hamuduruwo’s face which appeared

to be wearied from some conflict or another.

Finally the Hamuduruwo himself understood the meaning of the hunter’s

gaze. After a few moments of reflection, the Hamuduruwo spoke

falteringly.

‘Yes, you are correct. I am unable to meditate in peace. In the early

hours of the morning one of Mara’s daughters arrives in the form of an

angel. She caresses my entire face with her soft fingertips. My

composure is shaken. I close my eyes tight and refuse to look at her.

She does not leave me. She leaves, but returns to me again.

The Hamuduruwo remained for a long time with his eyes closed.

‘You are a hunter. It would be good if you protected me from tonight

onwards instead of the jungle that surrounds me. I can then meditate in

peace in the knowledge that these evil females will not arrive knowing

that you are by my side.’

It took the hunter a long time to understand this directive. He had

realized again and again, even after he took the gun, that he had become

a hunter.

And yet he did not remember the Hamuduruwo ever having told him to

expend his services in this way, by the Hamuduruwo’s side.

After a long time something strange had transpired on top of this

rock that stood in the middle of the jungle. The hunter tried to carry

out his diurnal tasks as though nothing strange had happened. He roasted

rice in the kitchen hearth, turned it into flakes, mixed it with honey

and offered the noonday meal to the Hamuduruwo along with some fruit.

With this the heaviest task of his day was done.

In the evening he cut open three pomegranates, squeezed the juice out

and made ready the offering to the Buddha. The two remaining parts he

poured into the Hamuduruwo’s bowl. The Hamuduruwo took the poojawa to

make his offering to the Buddha. The hunter took one pomegranate and

tore into it as would a gorilla and started his way down the hill.

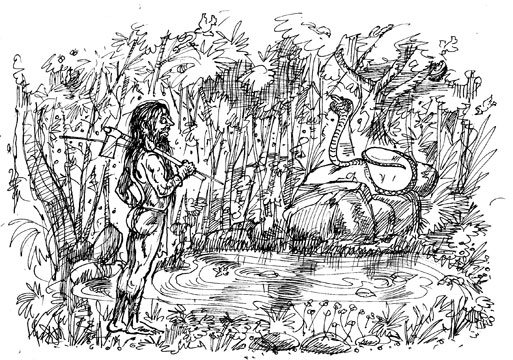

Half way down the rock there was a pond filled with ice cold water.

The moment his eyes touch the water, he gets goose bumps. The hunter,

who wears not a stitch apart from his loincloth, never felt the cold,

not even in the coldest nights of January. The water here was still and

yet the moment his eyes fell on it his muscles broke out in the manner

of a wild animal. He got goose bumps. The Hamuduruwo called him a

hunter. He remembered this again. He wanted to walk past the pond but

his legs carried him towards it. The conflict in his mind did not last

long. He looked at the hole in the rock at the far end of the pond more

out of habit than anything else. He loosened his loincloth and lay down

on the rock in full view of the cave. The sun went down in the western

sky and the sounds of day subsided and gave way to those of the night.

His eyes and ears were oblivious to all this. Like the Hamuduruwo he was

as though in deep meditation, his half-closed eyes directed at the cave.

He had involuntarily taken hold of one end of his thick moustache. Like

a buffalo chewing the cud, he sucked on it. Half way down the rock there was a pond filled with ice cold water.

The moment his eyes touch the water, he gets goose bumps. The hunter,

who wears not a stitch apart from his loincloth, never felt the cold,

not even in the coldest nights of January. The water here was still and

yet the moment his eyes fell on it his muscles broke out in the manner

of a wild animal. He got goose bumps. The Hamuduruwo called him a

hunter. He remembered this again. He wanted to walk past the pond but

his legs carried him towards it. The conflict in his mind did not last

long. He looked at the hole in the rock at the far end of the pond more

out of habit than anything else. He loosened his loincloth and lay down

on the rock in full view of the cave. The sun went down in the western

sky and the sounds of day subsided and gave way to those of the night.

His eyes and ears were oblivious to all this. Like the Hamuduruwo he was

as though in deep meditation, his half-closed eyes directed at the cave.

He had involuntarily taken hold of one end of his thick moustache. Like

a buffalo chewing the cud, he sucked on it.

The objective of his anticipation arrived, sliding out of the cave.

She is the Naga Manavikava that spends days upon days within the

cavernous bowels of the rock and emerges on certain evenings. She came

out and stood still. He was convinced that she was looking at him. At

the same moment he heard a ‘poosh…poosh’ sound behind him. He knew this

sound very well. It was the Naga Raja that guarded the treasure hidden

behind the Viharaya. He knew that the Cobra was looking at the Naga

Manavikava beyond him and signaling her as he approached. The hunter did

not turn to look.

The hunter was hypnotized by the beautiful and small hooded head of

the Naga Manavikava. He deliberately avoided looking at the Naga King.

He didn’t look at the splendid and handsome creature almost as though

such a glance would evoke in him a jealous hatred. The Naga Manavikava

unfolded her hood and began swaying to and fro in the manner of

beginning a dance. His peripheral vision caught sight of the Naga King

slithering towards her. At the same time the snake that had been still

and quite within him began to come to life and uncoil. It too struggled

with the desire to proceed towards the Naga Manavikava. And yet the

hunter stood his ground like an enormous tree that had sunk deep into

the soil its roots. All he did was to spread his legs just enough for

the Naga Manavikava to be able to see the slow dance of his snake. The

Naga King who protected the treasure was not by her side, hood touching

hood, bodies entwined in slow dance. If the hunter so wished, his Naga

Raja would in an instant be grapping with the Naga King in deadly

battle.

The hunter knew that his cobra would easily slay the Naga King. He

also knew that if it so happened it would spawn a hatred that will live

from one lifetime to the next and the next thereafter and so on for

centuries upon centuries. Knowing well the signs of such altercations

and their adverse effect on the natural patterns of existence and

co-existence in the jungle, the hunter caught hold of his Naga Raja in

his hand and held it still.

Once or twice it escaped his grip and directed its hood which was

filled with the blood-desire hvgbt60 blood-hatred towards the Naga

Manavikava. The hunter recalled the sorrow-filled countenance of the

Hamuduruwo who spent his days and nights in the exercise of

self-control. And in an instant the Naga Raja spit out the hatred and

desire that had so filled its being and like a heart that becomes

lifeless trembled and then lay still. The hunter fell as though his body

had become like an empty anthill. Wearied by the torture of desire and

the grip of the hunter’s strong fingers, the Naga Raja began to retreat

into the empty anthill body of the hunter.

The hunter felt that his entire body had been warmed as would an

anthill heated by the lava deep within the earth’s bosom. He left his

loincloth upon the rock and stood up. He entered the pond.

He did not feel its cold now. His flesh did not break out in goose

bumps. He stayed in the water for a full half hour. As on land his eyes

remained half-closed, half-open. And in the water countless number of

tiny creatures of countless colours began dancing the dance that spoke

of the countless creatures across the limitless universe.

Fully satiated by the cool water, the hunter put on his loincloth and

began descending the rock once again. By the pond the premises of the

Naga Manavikava was but an empty cave.

His being was filled with thoughts that spoke of the co-existence of

all creatures, those with legs and those that slithered. In the great

earth there were countless other caves, other crevices. He too was but

just another empty cave. And in this earth there were countless other

snakes.

|