Trap guns - a growing threat

by Vidya ABHAYAGUNAWARDENA

A six-year-old girl was killed by a trap gun right in front of her

father, in Galagamuwa in the Kurunegala district early December. This

was the latest trap gun-related death in Sri Lanka reported in the

media. The accident happened when the father was laying out the trap

gun, with his daughter looking on, and the gun accidentally fired.

|

|

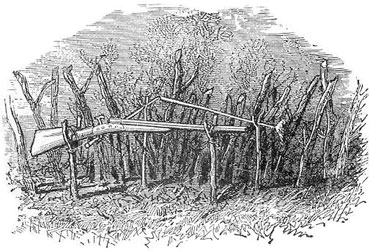

Elephants regularly

fall victim to trap guns |

The same month, a police sergeant was seriously injured by a trap gun

when a team of police officers was conducting a raid on an illicit

liquor (kasippu) den in Hataraliyadda in the Kandy district.

Those are just a few incidents that were reported to government

authorities and the media, but there are many more incidents related to

trap guns in Sri Lanka which are not being reported due to various

reasons. For instance, most victims are family members, relatives or

friends of the person who laid the gun.

Sometimes people hire trap gun setters to prepare and lay the trap

gun in the intended land and subsequently become victims themselves.

Under such circumstances, some of the trap gun-related incidents are not

reported and many victims usually seek medical care in their own homes.

Each year, people get killed, are permanently disabled or otherwise

injured due to trap guns which have become an increasing threat not only

for humans, but also for wild animals in Sri Lanka. Victims of the trap

gun include children, women, farmers, police officers, homeguards and

Wildlife Department officials.

History and evolution

Historically, people used different types of traps, but not trap guns

to catch animals and protect their agricultural land and crops from wild

animals. Those traps were usually made of rope or iron wires.

The trap caused minimal harm to humans compared to today’s modified

trap gun which can kill or disable a person on the spot.

The trap gun is not a sophisticated weapon. To prepare a trap gun is

less costly and does not require sophisticated technology. It only needs

a metal pipe, metal pallets and explosives which can easily be found

from firecrackers, explosive remnants of war (ERW) or readily available

explosive chemicals.

The trap gun has a feature that is similar to most landmines: both

are activated by the victim. Victim activated devices can never be used

exclusively for the intended target.

The trap gun is hardly visible to the naked eye, and its trigger line

(maru wela ) camouflaged in the jungle. In this background, innocent

humans and wild animals are facing increasing threats from the trap gun.

It is the indiscriminate nature of those devices that make

victim-activated landmines and the trap guns so dangerous and vicious.

The law

The Sri Lanka Firearms Ordinance No. 33 of 1916, has no specific

definition for the trap gun. The Firearms Ordinance for small arms and

light weapons provides the legal framework for civilian licensing,

importation, sale, transfer, manufacture, repair and possession of all

firearms.

The Ordinance has stipulated “gun” as: ‘Any barrelled weapon of any

description from which any shot, pellet or other missile can be

discharged with sufficient force to penetrate not less than eight

strawboards, each of three sixty fourth of an inch thickness placed one

half of an inch apart, the first such strawboard being at a distance of

fifty feet from the muzzle of the weapon’.

Within this Ordinance comes the practical explanation of a gun, “the

shooter pulls the trigger for the chosen intended target”. The trap gun

does not fall into this category.

Under these circumstances prosecution for the manufacture of trap

guns is minimal. Article 17 of the Firearms Ordinance states, “No person

shall manufacture any gun without a licence from the licensing

authority”. Under this Ordinance the trap gun falls into the illicit

small arms category. In these circumstances the manufacture, possession

and assembly of trap guns are illegal.

Their use

According to the law, to possess a licence for a firearm, a farmer

needs to have a minimum of five acres of cultivated land. Farmers with

less than five acres or those who cultivate others’ lands are left

vulnerable and not entitled to a licensed firearm. Thus they resort to

using the illicit trap gun to protect their livelihoods. This problem is

particular in some districts such as Polonnaruwa, Anuradhapura, Matale,

Ampara, Kurunegala, Moneragala, Badulla and Ratnapura.

Today, Sri Lanka’s agriculture-based rural economies rely on illicit

trap guns to protect their crops and livestock from wild elephants,

boar, deer, porcupines and leopards and also for poaching. This is an

unacceptable and cruel way of protecting crops from wild animals.

Most of the time, in the name of protecting agricultural land, people

use trap guns to kill wild animals for economic purposes such as for

meat, and for animal skins and body parts such as tusks.

For some people this has become a lucrative business activity as

there is a huge demand for those products in the market.

Today, people also use trap guns for other purposes - for economic

activities such as ganja and cannabis cultivation, moonshine production

sites, gem mining, illicit logging and illegal timber industry in the

jungle. With this background trap guns are used in all parts of the

country and it will become a threat for human life and animal life in

Sri Lanka.

Socio-economic and environmental costs

From ancient times people maintained friendly relations with the

forest or jungle for their day-to-day living activities such as to find

firewood, wild herbs for ayurvedic medicine, food, chena cultivation and

hunting.

But those activities did not substantially harm the ecological

balance or destroy the environment. Activities were also carried out

without any commercial purposes compared to today’s reasons for use of

the trap gun.

Sri Lanka’s total population today is a little over 20 million of

which 17 million are rural poor with their daily life depending on

agriculture-based economic activities. Most of the trap gun-related

incidents are from the rural agricultural sector in Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka’s total population today is a little over 20 million of

which 17 million are rural poor with their daily life depending on

agriculture-based economic activities. Most of the trap gun-related

incidents are from the rural agricultural sector in Sri Lanka.

The use of the trap gun for protecting farming is not the solution,

and also if there is human death or injury, huge social and economic

costs have to be borne by the victim’s family and society.

Trap gun victims appear to accept the injuries passively and often do

not seek proper medical attention. There is no record about these

incidents with the authorities such as police or hospital personnel.

Sometimes, injuries lead to death, but that does not seem to

discourage people from the use of this weapon again and again.

Trap gun victims in remote areas i.e in jungles, increase their risk

of death due to the victim having to travel long distances to get

medical attention. Many of the trap gun-related cases have led to

amputation.

According to the administrative reports of the Inspector General of

Police, 80 deaths were recorded in relation to trap guns from 2003 to

2007. The Government has to spend a tidy sum of money for trap gun

victims - long stays in hospital and medicine. This occurs if the victim

needs extra medical attention such as surgery, prosthetic limbs and

rehabilitation.

According to Judicial Medical Officer Anuradhapura, Dr. D.H.

Widyaratne, “Every year, over 200 trap gun victims are admitted to the

Anuradhapura hospital. An injured person has to stay between five and 20

days in hospital and the cost of medical care and other hospital

expenses for a person with trap gun injuries is around Rs. 250,000 to

500,000. The Government has to bear the cost”.

He further emphasised the inhuman side of the trap gun setter. “Once

the trap gun is put in place, the setter is always alert until the gun

goes off.

Then the trap gun setter rushes to the site and if the victim is a

human, the setter immediately leaves the place as otherwise, he will be

identified. The victim has to suffer pain and agony until someone finds

and takes him or her to hospital. If there is a delay in reaching the

hospital, the victim’s life is in danger,” he said.

There are also socio-economic ramifications for the affected person’s

family. If the breadwinner of the family dies or is disabled

permanently, the family has to face many socio-economic problems.

Due to population growth, the demand for land for development,

agricultural and other activities is escalating. This has led to

extensive habitat destruction of wildlife. Sri Lanka is now experiencing

the human-animal conflict in alarming proportions.

The ongoing human-elephant conflict has claimed many human and

elephant lives in Sri Lanka.

Up to September 2010, there were 73 human and 173 elephant deaths

according to the Department of Wildlife Conservation. In a joint

publication of Saferworld and SASANET in 2008 on ‘Trap guns in Sri

Lanka’ - a wildlife officer from Anuradhapura noted: “I have personally

witnessed many occasions in my career [when] many elephants have been

killed due to trap gun injuries.

The damage to the front leg makes [an] elephant immobile [so] it dies

of hunger, thirst and infected wounds.” When the forest, jungle or

agricultural land are installed with trap guns, such places are not safe

for animals.

There are endangered species such as leopards in the forests of Sri

Lanka and they can be easily targeted by the trap gun. Tuskers and other

elephants, wild boar and other wild animals live in danger due to-this

illicit trap gun.

Broader approach needed

Sri Lanka needs to ban the use of trap guns. Once the trap gun is

banned, it will be easy to prosecute the perpetrators.

Sri Lanka needs to amend the Firearms Ordinance No. 33 of 1916. To

have a licensed firearm, a farmer needs to have a minimum of five acres

of crop land.

Existing laws need to be used effectively until amendments are

introduced.

The police needs to be more responsible. An awareness campaign is

much needed for affected communities, highlighting the impact of trap

guns. This can be carried out to enhance the safety and economic

viability of affected communities.

The crops and livelihoods of poor farmers need to be protected from

wild animals, otherwise their economic life will be severely affected.

Most agricultural farming in rural Sri Lanka is not insured and any

losses have to be borne by the farmer. The Government should look into

this matter seriously to protect farming activities from wild animals

and protect lives. A new insurance scheme for farmers can be a prudent

approach.

Putting up electric fences with uninterrupted power supply is only

one solution. Parallel to this is the need to find solutions for

communities to find non-timber products from the forest. Otherwise the

electric fence becomes a barrier for rural communities to engage with

the forest.

Putting up national parks and conservation areas as well as policing

wildlife corridors can minimise the human-elephant conflict to a greater

extent. The Department of Wildlife should take this up as a national

issue.

The authorities need to encourage farmers to use non-harmful (to

humans, animals and environment) methods i.e. traditional ways of

protecting crops at night, especially from wild elephants, by making

loud noises, lighting firecrackers and other environmental-friendly

methods.

Ongoing development and economic growth should trickle down

throughout the economy, benefiting rural youth, in particular to find

employment opportunities, start self-employment projects, quality

vocational training and to overcome poverty.

Then only can youth avoid working in illegal gem mining, illicit

liquor production and illegal timber industry in jungles, illicit

logging and cannabis cultivation.

This will benefit humans and animals and free them from

life-threatening trap guns and preserve the environment for future

generations in Sri Lanka.

The writer is a researcher in socio-economic development and has

worked in Colombo and overseas.

|