Sansaaraaranyaye Dadayakkaraya

(The hunter in the wilderness of sansara)

By Simon Nawagaththegama

Translated by Malinda Seneviratne

Chapter1 :(Part 3)

The hunter went to the indalolu tree at the foot of the hill and saw

the gun among its leaves. He looked at it long. The night was star laden

and although it was not too dark where he stood the darkness had

congealed within the covering of leaves. And yet his keen eyes were able

to see the gun clearly. He took it out, stood it against the tree and

once again gazed at it for a long time.

The Hamuduruwo had once again addressed him as 'hunter' that day.

He looked among the remains of a kumbuk log that he had set fire to

the previous day and found a live glowing ember beneath the ash. He

kindled a small fire out of it. He looked among the remains of a kumbuk log that he had set fire to

the previous day and found a live glowing ember beneath the ash. He

kindled a small fire out of it.

He sat by the fire, picked up the gun and emptied the gunpowder

completely. He cleaned the gun carefully. He reloaded and once again

wiped the gun carefully. He did nothing in haste but with slow

deliberation.

He had not had opportunity to engage in this kind of important hunt

from the day the gun came into his hands.

He did not forget to put out the fire completely. A fire can cause

harm to the unwary and overly curious creatures in the forest. The

smallest spark could cause a wildfire. He was not stupid enough to leave

a live fire unattended, having lived in harmony with the wilderness.

After the fire was out, he decided to ascend the rock. He picked up

the gun and kept it over his shoulder. He turned towards the rock. Two

bear cubs, one chasing the other in play, ran through his legs. The next

moment their parents, chasing after the little ones, stood facing him.

In the dim starlight he saw that the she-bear's nose had been hurt in

some accident. Two days previously she had not carried such a wound. He

was certain about this. He instinctively stretched him hand towards her.

The she-bear did not show any interest in his curiosity, need to offer

some kind of salve and kindness. She avoided his hand, looked at the

bear, and ran after the cubs. The bear on the other hand was slow. It

looked at him and followed the female in slow, lumbering steps as though

greatly wearied.

The hunter stood frozen, looking on as though one who was confronted

by unexpected obstacle. He felt that the gun on his shoulder had quietly

acquired some additional weight. He turned and walked to the indalolu

tree and placed the weapon on the crook. He stretched outwards the

fingers in his palms and watched the callouses break. He started his

ascent once more, this time empty handed.

He was not wont to hunt even the more dangerous of wild animals in

the jungle, such as bear for example. What dangerous creature was there

to turn gun upon from atop a rock that rose above tree line when even

elephants, bears and leopards were tame animals and not hunters? It had

to be assumed from the Hamuduruwo's hint that what was troubling him was

a species far more potent than the creatures of the jungle. What kind of

beast could torment the Hamudurowo by running 'soft fingertips' across

his cheeks? It was as though he had concluded that whatever the identity

of the tormentor, a gun would not be needed to face it. If he was unable

to fend off the detractor with his hands tonight, if necessary he could

tame it the following day with gun, whether the threat was greater than

that posed by a lion or tiger. The hunter dragged his great limbs up the

Mullegama Galkanda, without weapon, in the manner of one who had decided

that the gun would be used only if necessary and this too on the

following night.

He was not used to dwelling too long on 'delicate fingertips' and

'animals that torment with caress'.

Exactly at midnight, as though he had been prompted by an

hour-marker, the Hamuduruwo made his way with utmost calm to the Esatu

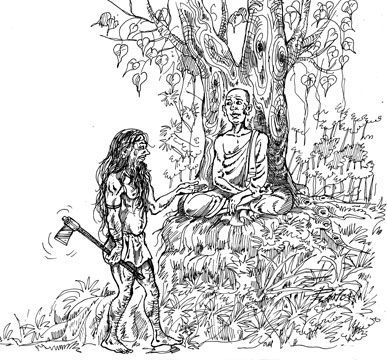

tree and sat under it in the lotus position. The hunter went to the

kaku-bo bush, took up position behind it and gazed through the leaves in

complete silence. It was as though memory of the incident of the bird's

nest had been totally erased.

It was an extremely silent night. Apart from the usual sounds of

forest creatures there was nothing to be heard. The only difference that

he detected was that the group of three elephants roaming in the jungle

behind him the previous day had arrived at a patch of trees on his

right. The baby elephant's stomach rumbled louder than usual, indicating

that it had been suffering from indigestion for several weeks.

The hunter didn't know if the Hamuduruwo had remembered that

surveillance on account of possible enemies had been solicited or

obtained. It was clear however that the Hamuduruwo did not pause to see

if the hunter was around. The Hamuduruwo had begun his meditation seated

under the Esatu tree at the other end of the rock as was the custom from

as far back as the hunter could remember.

The Hamuduruwo stood still, his back erect and hands folded over one

another. The hunter, seated some fifty yards away could see vein, sinew

and other markers that decorated the landscape of that serene face as

clearly as he could see the lines on a Bo lead less than a foot away.

Dawn was approaching. Although there was less rhythm than in the cry

and timing of their tame counterparts in the villages, a couple of

jungle fowl announced the arrival of the dawn. The hunted heard.

Instantly his sense of alertness became heightened. He immediately

detected a certain change in the time scarred facial muscles of the

Hamuduruwo. The Hamuduruwo's cheek was convulsing with intense feeling

and indeed torment. It made the skin wrap upon itself and then unwrap.

The Hamuduruwo was straining to keep his eyes tightly shut. There was a

thin stream of desire rolling down his cheek followed immediately by one

of immense sorrow. At that very moment the hunter saw the strangest

creature. A giant ant of proportions he had never previously encountered

had started walking all over the Hamuduruwo's face. Instantly his sense of alertness became heightened. He immediately

detected a certain change in the time scarred facial muscles of the

Hamuduruwo. The Hamuduruwo's cheek was convulsing with intense feeling

and indeed torment. It made the skin wrap upon itself and then unwrap.

The Hamuduruwo was straining to keep his eyes tightly shut. There was a

thin stream of desire rolling down his cheek followed immediately by one

of immense sorrow. At that very moment the hunter saw the strangest

creature. A giant ant of proportions he had never previously encountered

had started walking all over the Hamuduruwo's face.

The hunter had stood up without himself noticing this fact. He

approached the Hamuduruwo in the manner of stalking a prey. He took care

to approach from downwind in order not to alert the creature to his

presence and approach. As he was closing in stealthily another amazing

thing happened.

The ant began to shrink in size. By the time he was about a foot

away, the ant had become extremely tiny but was still crawling all over

the Hamuduruwo's face. The hunter felt that his breathing was louder

than usual. He held his breath and stretched his finger very slowly

towards the Hamuduruwo's face. The tiny ant left the Hamuduruwo's face

and crawled up the hunter's finger.

The face of the Hamuduruwo, wrinkled beyond wrinkling in the agonies

that had manifested themselves up to that point, instantly became calk

and composed. The tightly shut eyelids opened slowly and with utmost

calm. By the time the eyes were fully opened, the hunter had crushed the

ant to death with his other had. He placed the dead ant in his open palm

and extended it the Hamuduruwo, in the manner of an offered to eye and

gaze.

The Hamuduruwo cast his eyes on the dead ant. He continued to gaze at

it. The hunter remained with palm open in perfect stillness. And hour

passed. Then another and yet another.

The Hamuduruwo did not take his eyes away. Finally, just as the first

rays of the morning sun kissed the rock, a slight and mysterious smile

and one had not been seen in many centuries materialized itself dawned

upon the Hamuduruwo's countenance.

The Hamuduruwo closed him eyes quietly. The hunter for his part

withdrew his hands, placed them on his knees and gazed upon the

Hamuduruwo's face as though in the clutch of hypnosis.

As the sun rose, the Hamuduruwo's vein-ridden face with line and wart

wrought by time appeared to take on a golden hue. The Hamuduruwo's body

was by this time covered by a certain glow.

After the hunter closed and opened his eyes for the first time from

nightfall to daybreak he saw the Hamuduruwo looking at him. It was a

face he had never seen before.

There was peace and equanimity of the kind he had never encountered

before in the shine of gaze. And the voice, when it awakened, was one he

had never expected to hear.

'Where is that she-ant you held in your palm? She was my wife four

times in sansara. Many thousands of times she was a prostitute, a bitch,

a cow-elephant, a doe....

'I triumphed over all the kleshas, all ants. You who came to my

assistance will also one day slay all the kleshas at the end of sansara

and attain the supreme bliss of nirvana.'

Thereafter the Hamuduruwo raised his eyes to the sky very slowly. He

let out long, an extremely long, sigh. The hunter looked at the sky and

for a moment felt faint.

His eyes were blinded for a fraction of a second by a strange glow

that had enveloped the

entire area. When he next opened his eyes, the Hamuduruwo in the

majestic manner of a lion lay at the foot of the Esatu tree in the

sublime and incomparable pagoda of parinirvana.

|