|

Vivi's poems: a new genre in Sri Lankan English poetry

Reviewed by Anil Padoda Arachchi

'nothing prepares you' is a collection of poems by Vivimarie

Vanderpoten, a senior lecturer at the Open

University of Sri Lanka, depicting a wide spectrum of themes with

ardent and vivid delineation of intense

conception and sensibility of passion imbued with transient aspect

expounded in Buddhist philosophy.

Though this view is universally felt to be a common one, Vivi's power

of language, rays of creativity and

gleams of genius have an array of meditative poems for the reader to

intellectually fathom into their subject.

' Has sorrow nothing to lose ' Has sorrow nothing to lose

Does it therefore sing?

Joy, fearful of envy,

remains silent.

While sadness speaks

does happiness hushed

refuse to tempt fate,

hold close to its bosom

clench tightly

the few treasures

collected from the

debris'

(Page 10)

The poet's words dilute into harmony with profuse and irrepressible

emotions to question "why do you only

ever write sad poems..." and to provide an indirect answer sought

from Buddhist doctrine. Personification

of sorrow and happiness in which sorrow 'sing(s)' and happiness

'hushed' brings out the appearance of

mundane life submerging the reality of life - impermanence and

transience- where happiness is only 'the

few treasures collected from the debris.' The definite article 'the'

before the word 'few' the word 'collected'

and the imagery of comparing happiness to 'a child who/on the beach

has found/a few bits of/coloured

glass' capture the essence of Buddhism.

What strikes me most is Vivi's philosophy which I personally feel has

been shaped and moulded by

Buddhist philosophy.

In the poem 'Desire', she uses the hackneyed metaphor - desire is a

moth- to query the essence with a

liberal perspective which itself is an ingrained aspect of Buddhism.

'Desire is a moth

drawn to the flame

we are told;

it stutters stupidly

towards

fire

then, wings singed,

destructs.

time-tested truth

notwithstanding

I can't help but wonder

Does the flame

bear no blame

for the ruin '

of gauzy wings? (Page 17)

Here the flux of words, the alliteration in 'stutters stupidly' and

the half rhyme and short 'i' sound in 'wings

and singed' picture how easily we are attached to lustful world and

get ourselves destroyed simply because

of our stupidity and ignorance. Her argument also makes us think

whether ignorance is a phenomenon that

exists irrespective of if it is perceived by us. For me the word

'gauzy' implies the disease-stricken, fragile

world. It can also mean material made of a network of wire

symbolizing the modern world caught in

complex patterns of life. Placed in this context, what Vivi does here

is to delve into Buddhist philosophy to

comprehend the intricacies of life itself.

In Buddhism, 'Insight meditation' refers to understanding the very

truth or the reality of things found in the

world smothered in a veil of ignorance. In 'Bridesmaid', Vivi is deep

in an insight meditation.

'I-

Alone in the crowded ballroom

Smiled and played my part

And after the show

Watched the flowers drop and fade

Heard the music waver into silence

And die

Like a smile

Like the flowers in my hand

Like love

Like happiness

Sometimes dies.'

(Page 29)

She sees death and decay in the flowers in her hand drooping and

fading and in the music dying down. What

really lies beneath the bright eyes, scent of incense, flashlights

from cameras, jewels and touting music is

nothing but death. She is cynically looking into the encroachment of

western values on the very fabric of our

society and inculcates in us that 'veil of ignorance' which indulges

us in a lifestyle distancing us from reality

of life. She paints a realistic picture of how the liberal economy

ushered in by capitalism spoils the sacred

values we upheld in 'Celebrating Love.'

'Love is to be bought,

Given away to the

highest bidder

It lurks in shopping malls,

only for those who can

Afford it,

It reeks of cash and kitsch.'

(Page 43)

As related to everything in liberal economy, love is caught in the

tentacles of the octopus of buying and

selling, and is sold to the highest bidder. The word 'lurks' suggests

that love manoeuvres insidiously to get

itself bought. 'It reeks of cash and kitsch' presents a canvas of its

sentimentality on one hand and its

obnoxiousness on the other. It all boils down to the fact that people

are so ignorant and they cannot see the

depth of life.

Life is an astonishing thing and we are engrossed in admiration at

some of the transient modifications. The

vicissitudes of life obscure us from the wonder of our being.

Buddhism teaches you to be calm, quiet and

composed in face of both happiness and sadness and victory and

defeat. It teaches you to be content of what

you have today and not to be worried of what you do not possess.

Isn't the poem 'I Have Today' a

wonderfully crafted one portraying this aspect of life? This poem

moves my heart vehemently.

'But

Today

your fingers are entwined possessively

between mine

and your lips are sweet and warm as they

explore the secrets of my soul.

Today in your arms

I find a never-ending afternoon

Tomorrow,

Let the storm come:

I have today.'

(Page 78)

Life is a miracle. And so is the human mind. He who is absorbed in

exploring her soul today is to go away

from her tomorrow. Does this not evoke the feelings of temporary

nature of our relationships? Though the

tone is melancholic, in face of imminent separation she is calm,

restrained and sober with a profound

understanding of the transient nature of life.

According to William Wordsworth, 'the powers requisite for the

production of poetry are, first those of

observation and description, i.e. the ability to observe with

accuracy things as they are in themselves, and

with fidelity to describe them unmodified by any passion or feeling

existing in the mind of the describer.'

Reading Vivi's poetry, one can understand her ability to observe both

natural and social phenomena with

meticulous care and to imaginatively present them with a vision of

her own.

Her sensibility in perceiving the reality of what he observes is

discernable in all the poems found in the

collection. Her genre is innovative and different from that of all

the other Sri Lankan poets. I am of the

opinion her first collection of poetry will carve out a niche in the

field of Sri Lankan English poetry. I hope

she can be more Sri Lankan in her next collection of poetry.

Sansaaraaranyaye Dadayakkaraya Sansaaraaranyaye Dadayakkaraya

(The hunter in the wilderness of sansara):

By Simon Nawagaththegama

Chapter1 :

(Part 11)

Ancient stories

Stories close to the present

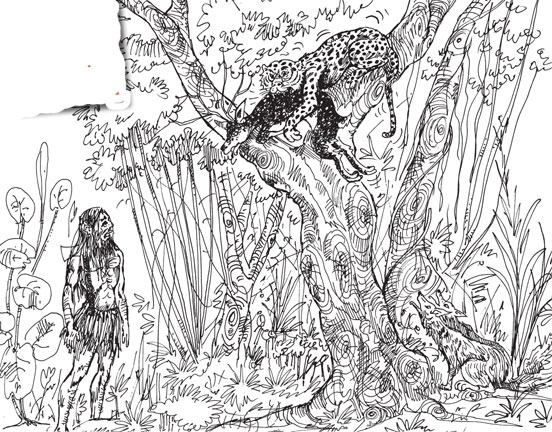

The Giant sat by a gigantic tree one early morning, his axe placed

against the tree trunk. Two foxes loitered

around him, sniffing the air. He knew why their noses were turned

upwards. The leopard had locked in the

crook of the tree the carcass of a deer it had preyed on earlier and

was leisurely having its fill. The Giant was

on his haunches, nibbling a twirl of his considerable beard in the

manner of a buffalo chewing the cud, deep

in thought. He did not lift a finger to wipe away the occasional drop

of blood that fell from the tree. He did

not show any interest in moving to another spot either. The leopard's

was neither a good nor a bad act.

When hungry it sprang among a large herd of deer or other such

creatures, caught one and ate to his fill. It

would not bother them thereafter. Not until it was hungry again would

it take another life.

After a while the leopard started down the tree and slid down the

trunk, testing its claws against the bark. It

looked at the Giant for a while. There was no affection or malice in

his eyes. For this reason, emboldened,

the leopard came to him and licked off the blood that lay clotted

among his facial hair. By and by the Giant

pushed the leopard's snout away and stood up. He picked up his axe,

placed it on his shoulder, and began to

walk. As he approached the foot of the hill just as the first light

invaded the forest, he noticed that the she-

bear that had been lying there for the past three days had not moved

an inch. Upon seeing the hunter,

though, the she-bear got up and rubbed against his massive legs. It

fell on its back waving its paws in the air

as though inviting for play and started saying something to him.

The Giant stepped over the creature and moved away. He stopped as

though he had remembered something

all of a sudden, turned and came towards the she-bear. She had been

there for three whole days. Each time

she saw the Giant she would get on her back and wave her paws this

way, trying to tell him something. He she saw the Giant she would get on her back and wave her paws this

way, trying to tell him something. He

bent over her. He ran his fingers over her belly and through the

hair. He felt something strange under her

right armpit. He parted the hair carefully. She whimpered in pain. A

large cactus thorn had embedded itself

deep in the flesh. It had created a festering wound. He ran his

fingers gently around the thorn and with a

sudden jerk pulled the thorn out completely. The she-bear cried out

in pain and bit his arm. Her cries were

soft and grateful the next moment as she licked his hand and face. He

looked around and grabbed a handful

of a particular type of grass. He stuffed it into his mouth and

chewed it into a wad. This he then pushed into

the wound and spread what remained around it. He was not interested

in her immense gratitude. He pushed

her snout aside, stood up, placed the axe in the crook of a tree

trunk and measured heavy steps up the

hillside.

That day the Giant could not reach the summit. The Tree Spirit came

running towards him. He seemed

highly excited. He took the Giant's hand. Then he spoke thus in

somber tones, looking deep into the Giant's

eyes:

'Our Hamuduruwo has reached a new plane of comprehension; has turned

into a new path in the search for

Truth. I woke up almost in a dream this morning. I felt my feet

burning in some strange heat. I turned

around and looked. Our Hamuduruwo was not at the foot of the tree

deep in meditation as he usually would

be at this time. There were four strange creatures grappling with the

Hamuduruwo. Fire and smoke arose

from around their feet. I felt that Our Hamuduruwo would be enveloped

in flames the very next moment.

Our Hamuduruwo removed his robe and twirling it round and round

lashed at the flames on the ground.

With each stroke, one flame was snuffed out. Finally, the fire was

completely out and as the fire went out

Our Hamuruduwo's countenance took on the most peaceful look.

The four creatures gradually shrank in size and disappeared. The

Hamuduruwo wore his robe again and

once again took up the lotus position, totally at peace. I am certain

of this; the Hamuduruwo has reached a

different plane in the journey towards enlightenment.'

The Giant listened to all this. The only thing he understood was that

the Hamuduruwo had grappled with

some strange creatures. His hand immediately went to the axe on his

shoulder. He realized he had left it at

the foot of the mountain. He went past the Tree Spirit and walked

quickly towards the Esatu Tree. Seeing

the Hamuduruwo seated in absolute peace all thought of danger left

him. He slowed down. The Giant went

up to the Hamuduruwo and gazed upon that peace-filled face. There

were no signs whatsoever of any

struggle of the kind that the Tree Spirit had described.

After a while the Hamuduruwo opened his eyes and looked at the Giant.

He was happy to see him standing

there. Then, as though he had immediately ceased to appreciate the

Giant's presence and was gazing into

the distant horizon where tree line met sky, the Hamuduruwo began to

preach. The story perplexed the

Giant. The Tree Spirit had informed him that the Hamuduruwo had used

his robe to douse the flames of

some mysterious creatures, that these inflamed creatures had wrestled

with the Hamuduruwo. And yet the

Hamuduruwo expounded a discourse on his own garment.

'There is a Buddhist practice that I have been endowed with. The

Compassionate and All-Knowing One

once spake thus: "Adiththan bhikkave! Khelan va, seesan va,

ajdupekkhitva, amanasikaritva

anabhisamethanan chathunnan ariyasachchanan yathabhoothan

abhisamasaya, adhimaththo chando cha,

vayamo cha, ussaaho cha, ussolhee cha, appaticanee cha, sathi cha

sampagngnan cha karaneeyan" and so on.

He advocated that the bikkhus should in the interest of obtaining

full cognizance of the Four Noble Truths,

cultivate discipline, effort, practice, acute consciousness and

discerning wisdom showing equanimity

towards and being unshaken by a burning robe or an agitated mind.'

The Giant stood tall. His eyes were half closed. He expended much

effort to distill these words and obtain

meaning from them. Since the Hamuduruwo spoke of a burning robe and

not the creatures decked in flames

that had grappled with him, the words of the Hamuduruwo perplexed him

even further.

'The worst that the neglect of a burning robe or a mind in flames can

produce is a single death. Entrapped in

a bonfire a person cannot die seven or eight times but just once. The

inability to comprehend the Four

Noble Truths, however, will ensure a countless number of births and

consequently a countless number of

deaths.'

The Hamuduruwo, having reached a certain plateau in his journey

towards Enlightenment and one which

was mysterious to others and for this reason compelled by great

compassion towards such creatures,

continued to speak to some invisible person right before him or to

the far away horizon or to the open sky.

'There is no limit to the sorrows of birth, decay and death that a

single creature has to suffer through the

long span of sansara.

The dependent originations pertaining to the five aggregates are made

of and for the sorrows of unpleasant

association, the sorrows of separation from pleasant associations and

so on.

If the full volume of sorrow's harshness was so much, if the weight

of nirvanic harshness and sorrow was so

much, if so much were the nirvanic bliss and the fearfulness of

sorrow-weight, then that much would be the

unspeakable lightness of nirvana as well...'

BOOK LAUNCH

Ali Baba saha Horu Hathaliha

Veronica Jayakody's children's story book Ali Baba saha Horu

Hathaliha will be launched at Dayawansa Jayakody Bookshop Colombo 10 on

March 15 at 10 am.

The book has been written to appeal to both children and adults.

It is a Dayawansa Jayakody publication. |