Introduction to modern Latin American fiction - Part 1

The purpose of this Article is, in the first instance, to introduce

briefly the history of Latin America and the conquest and subsequent

changes to the ethnic and social landscape. Secondly, I will touch upon

the different modes of story telling both before and during the conquest

of what is today known as Latin American.

Then I will look at Modernism and explain how it is the precursor to

the literary Boom of the 1960s which put Latin America on the literary

map. My discussion on the Boom will include a brief explanation of

Magical Realism which is a key pointer in Boom. I will then discuss this

in relation to Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s “One hundred years of solitude”.

This will then be contrasted with Isabel Allende’s “The house of the

spirits”, illustrating the progression from what is known as the Boom to

the movement which followed it - the Post-Boom. This will include the

interface which exists between art and society and examine how Latin

American literature addresses matters of politics and both national and

personal identity.

The age of discovery and conquest is one of the most fascinating

periods in of the whole history of Latin America. The discovery and

subsequent conquest of the Americas was the single most important

cultural encounter in history, a sequence of events that rocked the Old

World and profoundly influenced events that were to follow and therefore

the New World.

The indigenous peoples of the Americas are the pre-Columbian

inhabitants of North and South America, their descendants, and the many

ethnic groups who identify with those peoples. They are often also

referred to as Native Americans, Aboriginals and First Nations.

Application of the term "Indian" originated with Columbus, who

thought that he had arrived in the East Indies, while seeking Asia.

Later the name was still used as the Americas at the time were often

called West Indies. This has served to imagine a kind of racial or

cultural unity for the aboriginal peoples of the Americas.

Once created, the unified "Indian" was codified in law, religion, and

politics. The unitary idea of "Indians" was not originally shared by

indigenous peoples, but many over the last two centuries have embraced

the identity.

According to the New World migration model, a migration of humans

from Eurasia to the Americas took place via a land bridge which

connected the two continents across what is now the Bering Strait.

The most recent point at which this migration could have taken place

is 12,000 years ago, with the earliest period remaining a matter of some

unresolved contention. These early Paleo-Indians soon spread throughout

the Americas, diversifying into many hundreds of culturally distinct

nations and tribes.

According to the oral histories of many of the indigenous peoples of

the Americas, they have been living there since their genesis, described

by a wide range of traditional creation accounts.

Many parts of the Americas are still populated today by indigenous

Americans. Some countries have sizable populations, such as Bolivia,

Peru, Mexico,Guatemala, Colombia, and Ecuador.

At

least a thousand different indigenous languages are spoken in the

Americas and certain indigenous peoples still live in relative isolation

from Western society, afew

being counted as uncontacted peoples. At

least a thousand different indigenous languages are spoken in the

Americas and certain indigenous peoples still live in relative isolation

from Western society, afew

being counted as uncontacted peoples.

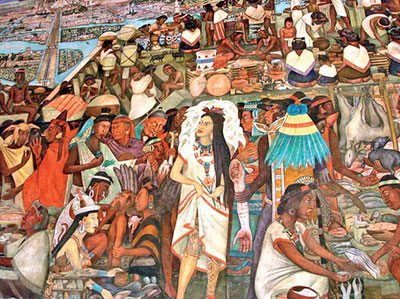

Many pre-Columbian civilizations established characteristics and

hallmarks which included permanent, urban settlements, agriculture,

civic and monumental architecture, and complex societal hierarchies.

Some of these civilizations had long faded by the time of the first

permanent European arrivals (late 15th–early 16th centuries), and are

known only through archaeological investigations. Others were

contemporary with this period, and are also known from historical

accounts of the time.

A few, such as the Maya, had their own written records. However, most

Europeans of the time viewed such texts as heretical, and much was

destroyed in Christian pyres. Only a few hidden documents remain today,

leaving modern historians with glimpses of ancient culture and

knowledge.

According to both indigenous American and European accounts and

documents, American civilizations at the time of European encounter

possessed many impressive accomplishments. For instance, the Aztecs

built one of the most impressive cities in the world, Tenochtitlan, the

ancient site of Mexico City, with an estimated population of 200,000.

American civilizations also displayed impressive accomplishments in

astronomy and mathematics. American Indian creation myths tell of a

variety of origination of their respective peoples. Some were "always

there" or were created by gods or animals, some migrated from a

specified compass point, and others came from "across the ocean".

Conquests and treaties

The first explorations and conquests were made by the Spanish and the

Portuguese, immediately following their own final reconquest of Iberian

lands in 1492. In the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, ratified by the Pope,

these two kingdoms divided the entire non-European world between

themselves, with a line drawn through South America.

Based on this Treaty, and the claims by Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez

de Balboa to all lands touching the Pacific Ocean. With help from their

powerful Indian allies, the Spanish rapidly conquered territory, with

Hernan Cortes overthrowing the Aztec and Francisco Pizarro conquering

the Inca Empire.

As a result, they gained control of much of western South America,

Central America and Mexico by the mid-16th century, in addition to its

earlier Caribbean conquests. Over this same timeframe, Portugal

colonised much of eastern South America, naming it Brazil.

Other European nations soon disputed the terms of the Treaty of

Tordesillas, which they had not negotiated. England and France attempted

to plant colonies in the Americas in the 16th century, but these met

with failure.

However, in the following century, the two kingdoms, along with the

Dutch Republic, succeeded in establishing permanent colonies. Some of

these were on Caribbean islands, which had often already been conquered

by the Spanish or depopulated by disease, while others were in eastern

North America, which had not been colonized by Spain north of Florida.

As more nations gained an interest in the colonization of the

Americas, competition for territory became increasingly fierce.

Colonists often faced the threat of attacks from neighboring

colonies, as well as from indigenous tribes and pirates.

It is from the blend of European and indigenous cultures, which Latin

America is well known for that that the rich literary tradition has

developed.

Chronicles written by the Conquistadors

Pre-Columbian cultures were primarily oral, though the Aztecs and

Mayans, for instance, produced elaborate codices.

Oral accounts of mythological and religious beliefs were also

sometimes recorded after the arrival of European colonisers, as was the

case with the Popol Vuh. Moreover, a tradition of oral narrative

survives to this day, for instance among the Quechua-speaking population

of Peru and the Quiché of Guatemala.

From the very moment of Europes "discovery" of the continent, early

explorers and conquistadors produced written accounts and cronicles of

their experience—such as Columbuss letters or Bernal Díaz del Castillos

description of the conquest of Mexico.

During the colonial period, written culture was often in the hands of

the church, within which context Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz wrote

memorable poetry and philosophical essays. Towards the end of the 18th

Century and the beginning of the 19th, a distinctive criollo literary

tradition emerged.

The 19th Century was a period of "foundational fictions" (in critic

Doris Sommers words), novels in the Romantic or Naturalist traditions

that attempted to establish a sense of national identity, and which

often focused on the indigenous question or the dichotomy of

"civilization or barbarism".

At the turn of the 20th century, Modernism emerged; a poetic movement

whose founding text was Rubén Daríos Azul (1888). This was the first

Latin American literary movement to influence literary culture outside

of the region, and was also the first truly Latin American literature,

in that national differences were no longer so much an issue.

Modernist literature is the literary expression of the tendencies of

Modernism. Modernistic art and literature normally revolved around the

idea of individualism, mistrust of institutions (government, religion)

and the disbelief in any absolute truths. Modernism itself is marked by

a strong and intentional break with tradition.

This break includes a strong reaction against established religious,

political, and social views. Modernists believe the world is created in

the act of perceiving it; that is, the world is what we say it is.

Modernists do not subscribe to absolute truth.

All things are relative. Modernists feel no connection with history

or institutions. Their experience is often that of alienation, loss, and

despair. Modernists champion the individual and celebrate inner

strength. They believe life is unordered and concern themselves with the

sub-conscious.

It is Modernism that leads us onto the literary boom of the 1960s and

1970s which really put Latin American literature on the global map. Both

the Boom and post Boom literary genres will be examined in detail next

week. |