‘Fabliaux’,

farces and morality tales

The term “Fabliau” denotes a medieval literary genre: a short, tale

in verse with stock characters, realistic details, sexual

transgressions, obscenity, and a clever plot mocking human weaknesses

and making cynical fun of conventional notions of morality, authority,

and poetic justice. The term “Fabliau” denotes a medieval literary genre: a short, tale

in verse with stock characters, realistic details, sexual

transgressions, obscenity, and a clever plot mocking human weaknesses

and making cynical fun of conventional notions of morality, authority,

and poetic justice.

Deriving from the medieval French dialect word flabel or fablel,

“fabliaux” combine an original generic combination of the farce and the

dirty story. In the fabliau the “givens” are infidelity, opportunism,

trickery, and gullibility.

Considering their shocking and subversive content, these fables were

surprisingly popular in medieval France, especially between the

mid-twelfth and mid-fourteenth centuries.

Most were anonymous, probably composed by wandering minstrels,

usually termed jongleurs . Of the great number originally current, only

about 150 survive. Although the content is obviously low, there is still

academic dispute about whether the intended audience was bourgeois.

Their influence was naturally strongest in France, but there is an

anonymous Middle English fabliau, Dame Sirith , written in the late

thirteenth century.

Furthermore, elements of the fabliau are powerfully apparent in

certain works of Chaucer, Boccaccio, Shakespeare, and Chaucer’s

narrative compendium, the Canterbury Tales (1386–1400). Most concern

adulterous triangles, usually arising out of doting husbands who have

foolishly acquired sly, materialistic, and sexually adventurous wives.

Feminine agency

Medieval feminine agency is revealed often through a tertiary type—a

woman who appears at the margins and between the boundaries. She is

found in a number of Medieval genres and is often characterized as

intelligent, striking, resourceful and capable. She appears, at least

for a time, in male garb as a disguise.

Whether she emerges from an obscene and humorous fabliau, an

uplifting and noble roman, or even from a religious tale of a saint’s

life, she can be seen as willfully utilizing her skills and gifts to

overcome hardships, abuses of power, and social restraints and

proscriptions, all while achieving specific changes which can be viewed

from within the medieval literary and social context as just outcomes.

It is fascinating that in such a variety of medieval French literary

genres, there are so many women wearing men’s clothes. Considering the

pervasive influence of the Church at the time, and the prevailing

misogynistic attitudes toward women, it is surprising to find so many

heroines subverting or flouting gender roles in both dress and behaviour.

However, transvestism in theses tales provided women with

opportunities to exercise social and psychological agency and mobility.

It also served to reinforce medieval gender roles by emphasizing that

the resourceful female must adopt male characteristics in order to

realize her goals.

However, the cross-dressed woman is able to determine her own actions

while the more typical romantic heroine is still subject to conventional

hierarchical limitation. She is idealized, frail, ornamental, and in

need of rescue.

Cross-dressing and representations of female agency and feminine

intelligence in medieval texts also reveal underlying tensions about

sexuality, particularly as they are depicted in fabliaux settings.

Cross-dressing women often seek redress from a world of

oppression, abuses of power, and deception.

Honour

These tales also reveal a sort of trickery, which, when morally

employed in a quest for the restoration of honor, virtue, or good, lauds

the abilities of weaker elements of society.

As these characters negotiated the difficulties of their time, their

strategies and successful outcomes, while often funny and entertaining,

also served to encourage a good-natured and encouraging sense of social

worth and solidarity among similarly vulnerable listeners.

Women, as marginalized beings, have often been required to resort to

trickery. This is not only to realize some modicum of independence but

simply to survive the difficulties facing them. Their female wiles

emerge directly from independent thought, deception, curiosity and

resourcefulness.

Of all the Medieval French genres, the fabliaux are the best examples

of stories falling into the larger category of Trickster folktales.

Fabliaux share characteristics with their heroes or heroine; they are a

literature of the marginal. Fabliaux are seemingly foolish tales which

set reality upon its end, and they expose the absurdity and frailty of

the social traditions they mock.

Like the tricksters who so often occupy a central role in these

fabliaux, these tales are often vulgar, utilizing language in ways both

shocking and yet clever and effective;they often carry an explicit moral

message.

The fabliaux also resemble trickster tales in that they mimic

authority, satirizing and parodying the serious. Fabliaux tricksters set

themselves (and their genre) up against the courtly, the genteel, and

the privileged, and in the process, as often as not, they are also

setting themselves up for an illustrative fall.

Manuscript

In the medieval French world, tales such as the fabliau did not occur

in a vacuum. They were combined with other genres both in terms of how

they were transcribed and compiled in manuscripts, and in the ways that

they were told.

An evening’s entertainment could very well see a fabliau intermingled

with other more “lofty”, courtly tales, less scatological fables, and

poetry or songs. Among these were romantic stories which would often

double up as morality tales.

In examining Old French literature of the Middle Ages, a significant

change occurs with the birth of the courtly narrative.

As medieval narrators become more complex and self reflective, and as

they begin to explore underlying psychological motives, there is a

concomitant flowering of the idealized courtly lady—constructed both in

the medieval and often in modern literary criticism, as an archetypal

representative of the pure and perfect woman.

These remote ‘courtly ladies’ are held up as the standard against

which more ‘earthy’ feminine types, such as peasant girls and the

fabliaux women, who are compared and found wanting.

These women are often viewed as parodies of more ideal and romantic

type and the characters and genres are juxtaposed. It would be easy to

assume that since these characters occupy opposing categories. Their

traits would naturally be similarly conflicting.

In this view, less elevated tales such as the fabliaux provide

opportunities for feminine characters to possess active wit, cunning,

and cleverness while the romantic and idealized heroines of the courtly

literature are not characterized in this way.

Instead, they demonstrate passivity, nobility, purity, and beauty.

Some of the most popular romances of the 13th and 14th centuries are La

Chastelaine de Vergy, The Lancelot-Grail, Gui de Warewic, Roman de la

Rose ("Romance of the Rose"), Guillaume de Lorris (around 1225-1237) and

Jean de Meun (1266–1277).

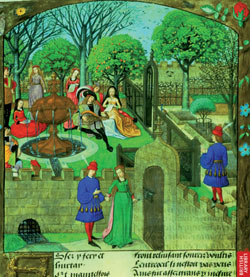

Roman de la Rose and related poetry

The most significant of 13th century romances is the Roman de la Rose

which breaks considerably from the conventions of the chivalric

adventure story. In a dream a lover comes upon a garden and meets

various allegorical figures.

The second part of the work (written by Jean de Meun) expands on the

initial material with scientific and mythological discussions. The novel

would have an enormous impact on French literature up to the

Renaissance.

Related to this romance is the medieval narrative poem called "dit"

(literally "spoken", i.e. a poem not meant to be sung) which follows the

poetic form of the "roman" (octosyllabic rhymed couplets).

These first-person narrative works (which sometimes include inserted

lyric poems) often use allegorical dreams (songes), allegorical

characters, and the situation of the narrator-lover attempting to return

toward or satisfy his lady.

The 14th century poet Guillaume de Machaut is the most famous writers

of "dits"; another notable author of "dits" is Gautier le Leu. King René

I of Napless allegorical romance Cœur damour épris (celebrated for its

illustrations) is also a work in the same tradition.

La Châtelaine de Vergy

Another extremely well known French Medieval romantic novel with a

moral message is La Châtelaine de Vergy. Some critics believe that it is

a Roman à clé - a novel in which actual persons and events are disguised

as fictional characters.

It tells the story of an un-named knight in the service of the Duke

of Burgundy who is the lover of the Châtelaine of Vergy (the wife of a

châtelain and niece to the Duke). The Châtelaine, has accepted this

knight's love on one condition: that he must keep their relationship

secret from everyone, and he is able to visit his mistress when, by

their pre-arranged signal, she walks her dog alone in her garden.

When the Duchess of Burgundy falls in love with the knight, he is

forced to spurn her advances. In her anger, the duchess then tells her

husband that the knight is unfaithful and has tried to seduce her, and

the Duke accuses the knight of treachery.

To save his honour, and to avoid being exiled (and thus forced to

distance himself from his mistress), the knight (once the lord has

promised to keep his secret) reveals to his lord where his heart truly

lies, thus violating his promise to his mistress.

The Duke reveals the truth of the knight's love to his wife, and, at

the feast of Pentecoste, the Duchess makes a cruel inside joke to the

Châtelaine about her lover and her "well-trained dog".

The Châtelaine realizes her lover has not kept his promise and she

dies in despair. The knight discovers her body and kills himself. The

Duke finds both bodies, and exacts vengeance on his wife by killing her

with the knights sword, and then becomes a knight Templar.

The romance consists of 968 lines of verse in 8 syllable rhymed

couplets (the work is in the same poetic form as the majority of

medieval French romans, although significantly shorter than the romances

of Chrétien de Troyes whose work was discussed in the previous column).

The work has come down to us in 10 manuscripts. The oldest extant

version was written in 1288, and the presumed date for the composition

of the work is 1271-1288.

The depiction of love in the work is exemplary of the courtly love

tradition, with its emphasis on a relationship between a brave and

handsome knight and a married woman, and on secrecy and utter commitment

to a mistress rules. The Châtelaine de Vergy was apparently very popular

in courtly circles. |