Revisiting Aravinda Jayasena in Wickramasinghe's Viragaya

Dr Siri GALHENAGE

‘The Buddha said to Venerable Upali, and his foster mother

Mahapajapati Gotami, “whatever Dhammas you know lead to nibidda...” This

beautiful word nibidda means revulsion from the world, pushing us away

from the things of the five senses.

It leads to Viragaya, dispassion or fading away, which leads to

nirodha, cessation, the ending of things, which leads to upasama – this

is perhaps the most beautiful term in the list – the peace and

tranquillity’.

[SIMPLY THIS MOMENT—Ajahn Brahm]

Many critics believe that Viragaya displays the best of Martin

Wickramasinghe’s literary prowess. His skill in crafting the personality

profile of Aravinda Jayasena, the protagonist of the narrative, makes it

unique among his many works of creative literary expression.

|

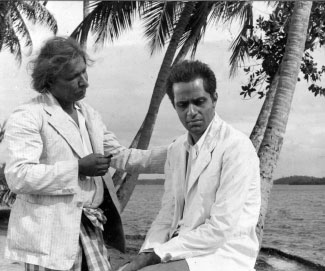

A scene from Viragaya |

Often dubbed the ‘psychological novel’, Viragaya’s appeal is in the

behavioural profile of Aravinda, which leaves the ‘psychologically

minded’ reader to mull over the complexities of his character. That

makes it the piece of art it is: ‘something beyond the tried and true’,

attracting international attention, leading to translations in Tamil,

English, French, Japanese, etc.

Viragaya is the autobiography of Aravinda Jayasena presented by Sammy

who was curious to discover his friend’s ‘inner self’ by reading his

memoirs, after his death. Sammy throws a challenge to the reader in his

epilogue: “what kind of man was he? If you can answer that question

after reading this, you must have a deep understanding of human

character and indeed of life itself”.

He asserted that demarcating the character traits of Aravinda was as

difficult as discerning the colours of the rainbow. On my part, I have

tried to look at the rainbow from several vantage points and have

admired its beauty, but will not expect the reader to believe that I

have seen all its colours!

The problem is: ‘there is each man as he sees himself, each man as

the other person sees him, and each man as he really is’. [William

James]

Buddhist family

Aravinda was born to a traditional Sinhala Buddhist family in the

South, presumably at the turn of the nineteenth century.

His father was an Ayurvedic physician held in high regard by the

village folk for his dedication to his profession, with no pecuniary

interest, although his colleagues considered him to be rather unorthodox

in his practice. With a desire to brush shoulders with the upper rung of

society, the native doctor had a strong ambition to make his son a

western-trained doctor.

Aravinda’s mother, on the other hand, had an affinity for the village

folk and wished her son to be a ‘good’ man than a ‘big’ man.

|

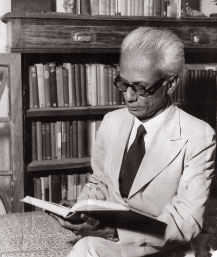

Martin Wickramasinghe |

Aravinda

was the younger of two siblings; his sister Menaka was described as

shrewd, controlling, temperamental, sharp-tongued and tight-fisted. She

was the dominant partner in her marriage, sensitive to local convention

but appearing to be partial towards her family. Despite his undoubted

affection towards his family—more so towards his mother—Aravinda felt

dislocated within his own family milieu.

Despite his good academic potential, Aravinda did not wish to succumb

to the pressure of his father in choosing a career in medicine. An

aversion for blood and the exposed human body [after seeing

illustrations of venereal disease], and having to dissect toads and

corpses, were given as reasons for not wishing to study medicine. Even

suggestions by his family to take over his father’s practice by

empirical learning of herbal prescription were turned down.

He selected subjects that inspired him rather than those which paved

the way for a professional career. He studied chemistry, and saw it in

parallel with alchemy, occult sciences and abhidharma. The shift in his

focus from science to the transcendental, in search of hidden secrets of

the universe, raised the ire of his teacher.

His ambition was to take up a less demanding job as a clerical

servant and to pursue his interest in alchemy, but was troubled by the

thought of having to go against his father’s wishes. The untimely death

of his father resulted in mixed emotions of grief and relief.

At school Aravinda desired the attention of those who opposed him, in

preference to that of his close associates. Although the school was a

happy place for him, he never desired to maintain the relationships made

at school. He believed that this approach to interpersonal relationships

led to his progressive isolation throughout life. After leaving school

he became increasingly introspective: “I tried to live within the world

of my own mind”. “My inward eye became fixed on the recesses of my

heart”.

Privacy

Aravinda believed in maintaining privacy in the expression and

articulation of love. He loved Sarojini [Sara] dearly, and was

physically attracted to her. She loved him in return, with the

expectation of their relationship evolving into a more meaningful one.

But Aravinda conveyed to her that he had no clear plans for the future

in terms of income, marriage and accommodation.

The strength of her affection towards him was revealed when she wrote

to him suggesting that they run away, in defiance of her parents’ wishes

to give her in marriage to a doctor or lawyer, and set up house in

another district and live in a de-facto relationship. “She didn’t care

for wealth, she wrote; she wanted nothing more than to live happily with

her husband, bearing his children and bringing them up to be decent men

and women”.

Aravinda was overwhelmed by Sara’s suggestion; he did not see beyond

meeting with her and dwelling in the happiness of talking to her and

dreaming of her love.

He relented and agonised over the social stigma attached to eloping,

and finally succumbed to his brother-in-law’s caution that he would face

the risk of prosecution for abduction as Sara was still a minor at

nineteen. He wrote back turning down Sara’s proposal. His cousin,

Siridasa, who also loved Sara, was affluent, self-confident and had a

clear vision about his future.

After gaining her parents’ approval to marry her, he also succeeded

in ‘winning her heart’. “He [Siridasa] was like a farmer preparing the

field; when she was ready to respond he would sow his love, to be

nourished by the warmth of her affection”.

Within two years of his father’s death Aravinda was faced with many

changes to his life and family. It became apparent that father had no

savings and had not ensured the financial security of mother.

To add to her despair Menaka produced a deed executed by father in

favour of Dharmadasa, handing over the house and property to him, in

return for the money he had borrowed from his son-in-law. Aggrieved by

this transaction and the escalating disputes between mother and

daughter, mother moved out of the family home permanently to live with

her sister.

Experimentation

Menaka came to occupy the house with Dharmadasa and their son,

Sirimal, but was soon to realise that Aravinda’s ongoing experimentation

with alchemy [trying to convert base metals to gold], causing a few

explosions, placed her son at risk.

This resulted in Aravinda too leaving the family home, which he would

have inherited by convention, and finding alternate accommodation in a

small house in a coconut grove beside a paddy field.

Aravinda found freedom in his new home. He pursued his interest in

alchemy and became increasingly preoccupied with Abhidarma and the

occult. He developed a friendship with Kulasooriya, a retired

postmaster, and was drawn to his way of thinking. Living a life of

detachment Kulasooriya ‘viewed the past without regret and the future

without fear’.

As the friendship grew Aravinda became more and more withdrawn from

society. He earned money only to meet his basic needs of food and

clothing. His emotions regarding the death of his father, parting of his

mother and the ‘loss’ of Sara faded away.

He reviewed his love for Sara:”the feeling that she had aroused in me

was nothing like a real passion, or love: it was rather a romantically

vague fondness for her-a passionless passion”. He believed he developed

a greater insight into human nature by learning from experience.

Dismissing any suggestion that his change in lifestyle was a result

of losing Sara, he detested any expression of pity by his family.

After moving into his new home Aravinda found a widowed woman [Gunawathie]

with an eight year old daughter [Bathee] to keep house for him. He

enjoyed having the little girl around attending to minor tasks, and

wondered whether he was getting too dependent on her. Aravinda became

the target of harsh rebuke by Menaka when she heard that he bore the

cost of Bathee’s education and that the girl had started calling him

‘father’.

As Bathee reached adolescence she started paying more attention to

her figure, grooming and cosmetics which made Aravinda re-evaluate his

feelings towards her.

“Bathee was no daughter of mine, no relative; she was merely the

daughter of my servant. When she was a child I had pitied her; as she

grew older pity had changed into something else without my even

realising it. By the time she became a grown woman pity had changed into

attraction”.

But when he came to know through Menaka that Bathee is seeing a young

man [Jinadasa], has written ‘vulgar’ love poems to him and had

encouraged him to visit her at night, he became overwhelmed with a sense

of impending loss, jealousy and anger.”I had been living in a dark,

strange world shaped by my own imagination. Bathee had brought a little

light into that world. I had been happy in the fancy that she would care

for me like a faithful slave until my death.

I was angry and disappointed now over the mere fact that she had

fallen in love with a young man, and not because the young man was a

driver”. After much thought, Aravinda decided to give Bathee in marriage

to Jinadasa and to buy him a car so that he could make a living as a

driver.

The so-called scandalous gossip regarding Aravinda spreading in the

village was too much for Menaka to bear. Employing a relatively young

woman, supporting her daughter in her education, and when she grew-up,

giving her in marriage with a dowry, provided much food for thought for

a gossip-hungry village community. Menaka came down heavily on her

brother accusing him of bringing the family to disrepute. She thought

that if he had their mother living with him he would not have been

subject to such innuendo!

Adolescence

After Bathee left home following the registration of her marriage to

Jinadasa, Aravinda experienced a deterioration in his health. He lost

interest in everything except Abidharma. He developed aches and pains,

became increasingly weak and was breathless on physical effort.

The Ayurvedic doctor declared that ‘years of neglect had led to

anaemia’. The patient did not respond to the medicines; in fact believed

that it made him worse. As he became more and more incapacitated he was

an invalid out of work after a medical assessment.

An attempt by Menaka to take him to her home to be nursed [the plan

supported by Sara] was rejected by him. But in the terminal stages of

the illness Bathee and Jinadasa took him to their home to be looked

after.

“Bathee nurses me with a care and devotion that I hadn’t seen even in

Menaka when she was nursing father. I would have found it incredible if

anyone had told me earlier that Bathee, who is not my daughter, sister

or wife, would show me such affection and sympathy”.

Personality

Embarking on an assessment of the personality of Aravinda Jayasena, I

was reminded of the adage: ‘like a sailor without a sextant, a

psychiatrist who sets out to navigate the dark waters of the unconscious

without a theory will soon be lost at sea’! I have sought the assistance

of several theories to guide me.

In his attempt at understanding human behaviour, Sigmund Freud

proposed a theoretical framework which, despite alterations with time,

has retained some basic elements.

Freudian theory of Psychoanalysis [Psychodynamics], if I may remind

the reader, divides the psyche into two domains—the Unconscious and the

Conscious, and three mental systems—Id, Ego and the Superego. The Id

occupies that part of the Unconscious mind which contains the

instinctual drives—sexual and aggressive.

The conscious part of the Ego, the moderator of all others, is in

touch with environmental reality. The conscious part of the Superego

consists of the individual’s moral and ethical conscience and societal

convention. The unconscious parts of the Ego and Superego are believed

to contain repressed fantasies and defence mechanisms.

It could be argued that faced with a series of challenges to his Ego

by powerful forces of convention {Superego], Aravinda gradually resigned

himself to a life of detachment.

He agonised over having to go against his father’s wish to make him a

doctor with intensions of ‘upward social mobility’, until his untimely

death eased the pressure.

He evaded the challenge placed before him by Sara to get married

against her parents’ wishes and without a marriage ceremony dictated by

custom.

Gossip

He suffered immensely at the hands of the local community who spread

malicious gossip regarding him and Bathee, raising moral concerns. “I

saw myself in spirit as a hero battling the flood, staunchly resisting

convention.

When the opportunity came to plunge in and show what I could do, my

strength just melted away and emotion overcame my judgement.

So convention always won the day”. The character of Menaka

[beautifully crafted by the author] was a destructive force on Aravinda.

She was a hypocrite: acting as the conveyor of moral standards of the

community, she was possessed with ‘primitive [Id] impulses’ of greed and

manipulation. Kulasooriya, on the other hand, was a stabilising force on

Aravinda’s Ego operations as they identified with each other in their

philosophy of life.

‘As the twig is bent, so is the tree inclined’: it is recognised that

childhood experiences have a lasting impact on an individual throughout

life.

Did Aravinda have unresolved and suppressed sexual anxieties that

extended back to his formative years? A Freudian would revel in the

thought of interpreting Aravinda’s aversion to the exposed female body

[developed after seeing illustrations of venereal disease] and his

dislike of dissecting human corpses [given as reasons to avoid studying

medicine] as arising from suppressed sexual and aggressive impulses.

Did such unconscious sexual anxieties contribute to his decision to

turn down Sara’s offer of marriage? With Sara, he didn’t see beyond

‘enjoying her company and dreaming of her love’. Sara as his ‘object of

love’ was replaced by Bathee by ‘transference’. “Sarojini’s image had

been gradually erased from my mind and Bathee’s had imperceptibly taken

its place”.

“My feeling for Bathee had developed insidiously into something like

the love I felt for Sarojini”. The battle within Aravinda regarding his

sexual impulses is brilliantly portrayed by Martin Wickramasinghe in the

following passage, when Aravinda called Bathee to his room on the night

before her marriage to Jinadasa.

“Before she came in I lowered the flame of the lamp a little. I was

afraid of betraying the confusion into which my mind had been thrown by

the conflict going on within me. Thoughts which must never be revealed

to Bathee or indeed to anyone at all kept rising in my mind. They were

thoughts which like evil spirits preferred darkness to the light”.

“I had often thought that Bathee would be by me to look after me and

to share my joys and grief as long as I lived”. Such a desire by

Aravinda seemed to be at variance with his move towards detachment, and

does raise questions about his emotional bonds and unmet affectional/

dependency needs during his formative years. He certainly felt

disillusioned with his family which fell apart after father’s death.

“Bathee and Sarojini were the only human beings left for whom I felt

anything like affection”. He fell into a state of melancholia after he

‘lost’ both of them, and in the final stage of his life ‘regressed’ into

a dependent ‘infantile’ state and had to be carried across to Bathee’s.

“I don’t need nursing—it is not that sort of illness”.

In many instances in his life Aravinda exercised his choice in an

idiosyncratic manner. This was more apparent in the subjects he selected

for study at school, the type of occupation he wished to make a living

from, the way he related to others, and even in the issues of love,

intimacy and marriage.

Choice is the central theme in Existential Theory, a philosophical

movement started by Soren Kierkegaard, which emphasised individual

existence and the freedom to act on one’s own convictions avoiding

systematic reasoning.

‘Man exists; in that existence defines himself and the world in his

own subjective way; and wanders between choice, freedom and existential

angst’. Aravinda took responsibility for the consequences of his

existence and did not place any blame on others.

He experienced plenty of anguish especially in relation to Sara and

Bathee [in different ways] but was averse to any expression of pity by

anyone.

According to the philosophical position of Existentialism Aravinda’s

personality is defined by the choices he had made, and not as reflected

through the interplay of conscious and unconscious mental processes as

postulated by Freud.

Quoting the work of Erich Fromm, ”To Have or To Be”, Dr. Gunadasa

Amarasekera in a brief commentary on the cover of The Way of The Lotus,

‘Viragaya’, states, “in Viragaya we see this dimension projected into

creative literary art, in the conflict between having and being in the

lived experience of human beings in a village in Sri Lanka”.

Menaka is the very epitome of ‘having’: miserly, hypocritical and

exploitative, driven by a desire to possess, placing self-interest

before human values.

Aravinda, although not infallible, is portrayed as attempting to take

the path of ‘being’, with ‘love, care, responsibility, respect and

knowledge’, as an alternative to the ‘destructive’ path taken by modern

man by ‘having’.

The philosophical stance of Erich Fromm, [a social psychologist,

psychoanalyst and social democrat] brings in a useful perspective to

look at the life of Aravinda from a socio-political point of view.

In contrast to the above abstract considerations of human nature,

phenomenology, introduced to psychiatry by Karl Jaspers, deals with

describing conscious human experience.

Once described, the deviation of such phenomena from normality is

judged by those with expertise, in a statistical or socio-cultural

sense, and the distress it may cause to the individual or others.

By his own admission, Aravinda did not have the ‘self confidence’ to

go against convention, and as Sara pointed out to him his ‘avoidance’ of

situations was due to his ‘lack of assertive skill’; all such phenomena

forming a cluster with his desired ‘dependence’ on Bathee.

It is rather poignant that Aravinda lapsed into a state of

‘depression’ characterised by ‘mental agony’, ‘loss of motivation and

interest’, ‘generalised aches and pains’ and ‘weakness’ after Bathee

left home to be married to Jinadasa. The associated development of

chronic anaemia, placed him at a ‘biological disadvantage’, posing a

risk to his life, which according to Scadding is the hallmark of a

disease.

The sub-title of the English translation—The Way of The Lotus--

points to the spiritual dimension of the narrative. Adopting a verse

from Anguttara Nikaya, the title is a metaphor for the path taken by

Aravinda: “Rising above the world into which he is born.

The Superior Being follows the way of the Lotus”. Was Aravinda a

superior being? With an interest in Abidharma, he had a propensity to

rise above the rest from his childhood.

He resolutely pursued a solitary course except for sharing some

common ground with Kulasooriya. He strove for self-mastery of his

senses.

As a child, his approach of gaining rapport with those who opposed

him at school was a harbinger to his future interpersonal relationships.

He experienced anger and sorrow as anyone else, but never expressed his

emotions, and with any build up of anger he turned it into compassion.

He has revealed his inner struggle at times to contain his passion

for the opposite sex or any impulses of the flesh.

He tried to be dispassionate towards the painful and to bear much

ridicule and contempt both from his sister and the local community,

exercising patience and forbearance.

Despite being accused of being either naive or cunning, he continued

with his obligations towards Bathee. Charity, he believed, should not

accompany any exploration of hidden motives of the recipient. He was

moderate in his eating habits and was free of any desire for status,

wealth or pride. He lived in the present, striving hard to free himself

from the past, and hence the future.

Aravinda writing during the last stage of his life, being looked

after by Bathee and Jinadasa: “I know that I will not survive this

illness.

But the sense of despair, of loss, of futility has left me, because

here kindness, love and affection are palpable human qualities”. Was his

alchemical explorations to find gold, a metaphorical quest to find peace

and tranquillity?

“For him, who has completed the journey, who is sorrow-less, wholly

set free, and rid of all bonds, for such a one there is no burning [of

the passions]” [The Dhammapada, Verse 90]. Aravinda may not have

completed his journey; he was certainly on his way.

***********

Whatever way one sees the life of Aravinda Jayasena: as a series of

conflicts between instinctual drives and convention; a struggle for

freedom and choice; a deviation from the destructive path taken by

modern man with a desire to possess; a spiritual journey towards peace

and tranquillity shedding off all passion; or simply the maladaptive

functioning of an inadequate personality, one cannot help being filled

with awe [with all the nuances of meaning of that word] at the depth of

intellect of one of our greatest Sinhala literary figures of all time,

Martin Wickramasinghe.

Like a Ruddy Turnstone, the migratory bird, that keeps turning stones

by the lake-side in search of feed, I have turned the pages of this

great narrative –Viragaya—looking for food for thought.

I fly away, like the winged creature, with a full stomach, but with a

nagging feeling that there may be many more stones unturned!

[This review of Viragaya was written after reading both the original

[Sinhala version], and its wonderful English translation –The Way of The

Lotus—by Professor Ashley Halpe.

The quotes are mostly taken directly from the English version and

does not reflect any expertise on my part on Sinhala to English

translation.] |