Re-smelling Romeo's rose

By Dilshan BOANGE

The works of William Shakespeare are foundational to the discourse(s)

of English literature. The works of the 'bard of Avon' have stood the

test of time to be treasured as carrying 'eternal truths' that explore

human nature and the ways of the world, and thereby deliver sagely

teachings couched in the beauty of poetic language. Many are the lines

from his plays that are still quoted in an everyday situation in the

manner of an aphorism; and it is one such Shakespearean line that I wish

to make the focus of this article.

|

|

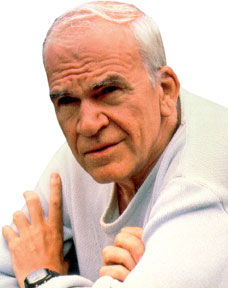

Milan Kundera |

In Romeo and Juliet we find one of the most well known stories of

tragic young lovers. This play also contains one of the most quoted

lines by the Bard -"What's in a name, that which we call a rose by any

other name would smell as sweet?" In discussing the relevance of this

particular line as an aphorism to apply in situations in life it would

be important to consider how it seems to negate the function of a name.

Certainly the sentiment expressed by the lovelorn teenage Romeo in afore

quote would not be applauded by modern day marketers who thrive on

'brand' value. And a name is very much the basis for branding, in that

sense.

The discussion I would like to build on is how the line written by

Shakespeare intended to portray the mindset of the young and naïve Romeo

is generally attributed to be an advocacy of the Bard himself in layman

interpretations. Yes, Shakespeare wrote the line, but does that suggest

it is his own belief and applies as absolutism? It is in exploring the

relevance of such a line as this that one can look at certain

postmodernist literary criticism, such as the French theorist Roland

Barthes's concept of 'The Death of the Author', which can be applied to

unravel greater interpretive scope of a text. Barthes propounded in his

essay "The Death of the Author" that a text can be divorced of its

author and allow the reader a greater autonomy to interpret what the

text may mean to him. This means to say that as a 'reader' one can and

should feel free to allow the meanings of the text to take shape in the

course of reading, rather than feeling it is only the creator of the

text (the author) who has the right to interpret it and that the

reader's role is to unravel the meanings, intentions and 'message(s)' of

the author embedded in the text and its narrative. Thereby in classical

criticism if an interpretation of a text by a reader may not seem to be

the very intention that the author intended to convey then such

interpretations would be declared as 'invalid'. In contrast postmodern

textual analysis/criticism offers much greater space for the reader to

explore possible 'meanings' of a text, regardless of whether or not they

were intended by the 'author'.

Often when one quotes Shakespeare (or any other writer or speaker for

that matter) it is done with reference to the source. The name (and

possibly even the work) is mentioned. This is of course ethically

required by norms in order to avoid being seen like a fraud who claimed

credit for another's creation. But on another level the mentioning of

the source and especially if it is a name held in great esteem in

society the name acts as a certificate to authoritatively assert the

validity of applying the quoted line to explain an idea or argument. It

is after all 'the words of Shakespeare' one could say and build ground

to justify ones stance and find sufficient safety and shielding from

critical attacks. In the essay "What is an author" the French

intellectual Michele Foucault charts the origins of the role of the

author in European society and how the 'author' over time gained a

position of eminence in society and thereby becomes an 'authority'. The

name of the author, his presence, and the authority he wields over the

text he creates is called by Foucault as the 'author function'.

|

|

A scene from Romeo and

Juliet |

|

|

William Shakespeare |

When one quotes the line "What's in a name..." is it to assert one's

views with the backing of Shakespearean thought? To strengthen one's

position in an argument and make the other yield by impressing on him

that he is up against the words of Shakespeare? But in such an instance

does one question the relevance of such a notion? Is it universally

relevant and applicable? One of the aspects to focus on is that the

flower is an item of 'materiality' and its fragrance (and possibly the

attributes of its appearance and texture of petals) is what is most

valuable. And if one cares to give thought to the 'context' in which the

line is used in the play, the relevance and application of a line such

as "What's in a name..." could become more evident. The line was used by

Romeo, and is meant to demonstrate the nature of his psychology. Romeo

is after all a teenager who is tormented by the fact that his sweetheart

Juliet is of the house Capulet, the sworn enemies of his own family, the

house of Montague, and thus wishes the burden of the 'politics' that

comes with the 'name' be made to vanish. A character in a work of

literature needs to be given certain autonomy to unfold in the course of

the narrative and need not necessarily reflect views and beliefs of the

author himself. Therefore it is the beliefs and mindset of the love

stricken teenage Romeo that comes out through the line of "What's in a

name..." If one were to divorce the name 'Shakespeare' (and the

authority that comes with it) as the one who wrote it, and looked at the

text (the quote) for its possible 'truths' and what relevance it holds,

then maybe the absurdity of accrediting that line a ground of

absoluteness would be very apparent.

In connection with this line of discussion I feel it is very

significant to cite a perspective of the Czech born postmodernist writer

Milan Kundera who in his quasi-biographical novel "The Book of Laughter

and Forgetting" speaks of the importance of a 'naming' and also

'renaming' in a 'political landscape'. Kundera deals with the subject of

identity in a significant way in a number of his works and in "The Book

of Laughter and Forgetting" speaks of how a 'name' is very much

political and can by no means be negated as insignificant. Kundera

believes that a name presents continuity with the past, and therefore to

replace or supplant one name with another is a 'political' act.

In an age of innocence, storm tossed amidst emotions of unrelenting

love and unyielding social prejudices, the young Romeo certainly wanted

naught but the sweet scent of his flower, Juliet. And to him a name

would be as the same as another or even possibly equal to namelessness.

But beyond the world of flora and fauna in the world of power and

ideologies perhaps Romeo's 'truths' in the lines "What's in a name..."

may find stringent limitations.

|