Fascinating excursion into the past, revisiting the colourful

personalities of the era

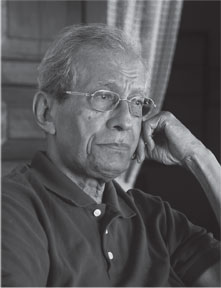

By Ranga CHANDRARATHNE

In this wide ranging interview, senior civil servant and prolific

author Bradman Weerakoon traverses the fascinating history of Kalutara

and the colourful personalities who dominated the era. One such

personality was Padikkara Mudliyar of Kalutara district Don A Silva

Wijesinghe Siriwardene (1888-1949) who constructed the legendary

Richmond Castle. The local elite of the era served as a bridge between

the colonial administration and its subject.

The author has detailed out some of the cardinal personalities of

Panadura like G.P. Malalasekara, Wilmot A Perera and Cyril Jansz who had

left gigantic footprints not only on the socio-cultural landscape of

Panadura but also on the cultural life of the nation. The coastal

township of Beruwela holds a prominent position on account of its rich

history and particularly of its contribution to cultural and linguistic

mosaic of the nation.

|

|

Bradman Weerakoon |

It is a multi-ethnic and multi-lingual constituency which had made

its unique contribution to the cultural and linguistic diversity of Sri

Lanka; apart from its predominant Muslim community, there are a sizable

expatriate community living in the area. The account on the road to holy

peak and towards Singharaja, deals with the important passage of history

revisiting the legend of the rebel Prince Vidiye Bandara.

It also recounts the Pahiyangala (Fa Hsien’s) rock cave where the

locals believe the great 5th century scholar monk rested on his long and

arduous journey on foot to the Peak. This part of the history is marked

by legends and folklore as well as the milestones in the post-colonial

history of Sri Lanka along the road to the Holy Peak. One such

historical landmark is the tree planted by the legendary Che Guevara,

when he came to Sri Lanka in 1959 to see how rubber was grown in

Kalutara.

Colonial times

Q: Kalutara Society in British Colonial times is an

interesting section which sheds light on the social life of Kalutara in

colonial times. You have cited the story of Padikkara Mudliyar of

Kalutara district Don A Silva Wijesinghe Siriwardene (1888-1949) as an

example for changing values and social behaviour of Sinhalese elites at

the time. Wijesinghe’s legacy the Richmond Castle is not only a

watershed in his personal life but also the social life of Kalutara in

colonial times and it also marks the rise of Sinhalese elite. How

important was that period in the colonial history which also marked the

emergence of native elite in the run up to the transition of political

power from colonials to natives?

A: This certainly was an important development and our social

historians and political theorists have written on the emergence of the

native elite, such as our Padikara Mudliyar of Kalutara. In my view they

represented an interesting bridge between the colonial administration

and the ordinary people. They served the valuable function of being a

resource regarding local habits, traditions and mores to the colonial

and in turn, either consciously or otherwise, communicated back to the

people the policies, attitudes and inclinations to the local people.

They contributed to a sharing between two quite contrary cultures –

one western and one Eastern. Being people in the middle, as it were, and

having a bit of both cultures - West and East, the native elite were in

the main the good intermediaries or middle men, who often get things

done. I believe this role they performed deserves more research. Usually

history records the achievements of the political leader. But the

contribution of these silent ‘people in between’ should not be

overlooked.

Of course, it must also be remembered that there were the usual

competitiveness and jealousies between the native elite themselves.

Kumari Jayewardene has highlighted these tensions in her fascinating

social history entitled ‘Nobodies trying to be Somebodies”. The

Somebodies in this instance were the mudliyars of the Siyane Korale with

their supposed links to the old aristocracy, if not to the nobility of

the feudal age.

They resented the so called lesser breeds who had come up the social

ladder on account of wealth acquired through arrack renting or the

plumbago trade – the Nobodies as they would have it. The Kalutara

padikars mudliyar would undoubtedly have had to face such taunts from

the so called aristocrats. The British colonialist playing his game of

divide and conquer would have lost no time in exploiting this faultline

among the native elite. To that extent the positive role the elite could

have played in political reform and constitutional development would

have been diminished.

Q: In the section on Panadura, you have explored Panadura from

diverse perspectives; from the singular contribution it made in the

post-colonial Sri Lanka in the revival of Buddhism and you have also

written about the great debate Panadura Vadaya and about the great

personalities like G.P. Malalasekara, Wilmot A Perera and Cyril Jansz.

How do you evaluate the contribution that Panadura made and its famous

sons?

A: I think people like these three, and Arthur V Dias, whom

unfortunately I have omitted in my English edition, (he is restored to

his rightful place in my Sinhala version) represent the dynamism which

Panadura and its remarkably inventive people gave to the country. More

and better education seemed the motif of their lives of service to the

community. One sees it in Wilmot Perera’s work on culture in Sri Palee

and in the pioneering impetus he gave to rural development long before

anyone else; Malasekera, one time Professor in Pali at the University of

Ceylon was a towering figure in the higher education area and emphasised

the importance of research and ‘inquiring’ into the roots of our

cultural inheritance especially through the growth of language.

He also stressed the lasting value of female education which is such

an important part of our national development. The early ‘movers’ and

‘shakers’ in establishing high - class institutions for girls to receive

education were the women of Panadura. Sri Sumangala Girls school in

Panadura and Visakha Vidyalaya in Colombo owe their existence to the

pioneering work of some great women of Panadura. Cyril Jansz who also

gave his life for education of children was a prime example of the high

place that the Burgher intellectual occupied in colonial society.

St John's College, Panadura was the cradle in which several future

leaders of the country were nurtured. Its students achieved fame in a

variety of pursuits – the professions of law and medicine, the arts –

music, drama, song, painting and sculpture; and in academia and

politics. As a mark of gratitude to Cyril Jansz the Government of the

time changed the name of the college he created to Cyril Jansz

Vidyalaya. It continues to maintain the legacy of excellence Cyril Jansz

endowed it with.

Unique township

Q: The coastal township of Beruwela is a unique township with

a fascinating history behind it. Among other things, you have mentioned

that Beruwela is a multi-lingual constituency where Tamil is an official

language. It is an important site where one can examine the history of

Moorish settlements in Sri Lanka.

How important is Beruwela as an example of ethnic amity particularly

in Southern province?

A: Actually Beruwela is in Kalutara which is in the Western

Province and my loyalty to Kalutara will not let it slip over to the

Southern province although it is almost on the provincial border. The

Muslims of Beruwela comprise a very important, influential and valuable

part of the cultural mosaic of the country. They are relatively well -to

–do and some of the residencies of the richer ones and the mosques are

beautiful to behold. As a rule Muslims all over are known for their

ability to get on with their neighbours and their trustworthiness in

business.

|

|

Bradman Weerakoon |

Although I found in my work among them that their household language

is generally Tamil, they have often acquired great facility in

Sinhalese. Excellent examples are their members of Parliament and other

elected bodies, for example, Bakeer Markar formerly a Speaker of the

Parliament and his son Imtiaz who was among the best Sinhala language

debaters at Ananda College, one of our leading Buddhist schools. I have

not enumerated the number of the community’s well - educated who are in

the gem and jewelry industry nor in the hotel and leisure sector of our

economy but I am sure the ratio greatly exceeds their proportion in the

general population.

I found a large number of the permanent - residence visa, foreign

expatriates live in and among the Beruwela Muslim community. This may

well be due to the overall attractiveness of the beautiful coastline

around here but it could also do with the non-intrusive and generally

‘welcoming of the outsider’ that seems to be a characteristic of the

locals. The regular five - hourly ‘call to prayer’ by the mosques

appears to be accommodated with appreciation by all around.

Q: On the road to Holy Peak and towards Singharaja are two

interesting chapters which not only trace the two roads leading to the

Holy Peak and the rain forest Singharaja but trace back a trail of

fascinating account of history rich with legends. Wasn’t it a journey of

discovery?

Journey of discovery

A: Yes, quite literally a journey of discovery to me, as it

would be to thousands of travellers who mostly go on the north –south

coastal road from Colombo to Galle. There is a lot of culture and

history on the two east / west roads, one through the north of the

district to Ratnapura and the Holy Peak and the other in the south of

the district through Matugama and Badureliya towards the Singharaja.

These two roads traverse the two Korales of the district – the Raigam in

the north and Pasdun in the south that are full of Sinhalese history.

The Kotte sub-kingdom of Raigama and in Pasdun Korale the hide-out of

the rebel Prince Vidiye Bandara who had a most colourful history. Some

of his daring exploits are recounted in the road to Singharaja as

Pelende, where he established himself and built a small palace (now the

site of the Raja maha vihare) are just off this road.

On the northern road on the ancient way to the sacred Peak you come

across Pahiyangala (Fa Hsien’s) rock cave where the locals believe the

great 5th century scholar monk rested on his long and arduous journey by

foot to the Peak. The Chinese government believes this happened and the

Embassy supports its restoration work. The Western Provincial Council

too votes money for the upkeep of this largely unknown historical site.

Lots of other things to see on the road to the Holy Peak including

the tree planted by the legendary Che Guevara ,when he came to Sri Lanka

in 1959 to see how rubber was grown. The southern road to Singharaja too

bristles with places to see and enjoy. The Rubber Research Institute in

Agalawatte, Gee kiya Kande – ‘the mountain of song’, rubber estate of a

famous son – Ronnie de Mel and the former camp site of the Kukuleganga

hydro- power scheme now turned into an admirable tourist- chalet resort

to serve as the final base camp for the assault on Singharaja.

Rivers and lakes

Q: In the final chapter, you have covered the areas of rivers

and lakes and mode of transport in Kalutara district. Transport and

development has inseparably linked together. How would you describe mode

of transport of the time such as buggy cart defined the life of colonial

era?

A: I think the mode of transport that defined the early

British colonial era was the double bullock cart – the bara karate. The

buggy cart was for the townsfolk and their little journeys. The bullock

cart was for hard work of transporting goods and people over many days

and long distances.

Manuka Wijesinghe’s Theravada Man recounts one such epic journey and

the carter’s songs that made such difficult journeys passable. The

haunting lamentation of the carter and his entreaties to his bullock

adapan pau karapu gono up the Haputale pass to the plantations beyond,

evoke memories of what life would have been in the developmental phase

of colonial history.

I read that the road to the holy Peak was the preferred route to the

hill country the gradient from Ratnapura being less steep than up from

Kandy via Ramboda. The local stories about the carts were that they were

made in Moratuwa (where else could the best and most up to date wood -

work come from) and the bulls obtained from Horana (no offence meant to

anybody living or dead).

The pace of change in transport from animal (the cart bull) or

natural (the sailing ship) of Portuguese and Dutch times to steam power

(the train) and steamship in British times were the main drivers of

development and the extension of that progress into the remotest parts

of the district of Kalutara.

Though train services remained only to serve the coastal dweller

transport development at the beginning of the 20th century when the

first motor vehicle and omnibus appeared in the country presaged

penetration into the hinterland. The opening up of vast tracts of jungle

for rubber plantations caused problems as well as benefits. One of the

unexpected developments was the immigration of thousands of Indian Tamil

labour for work in the rubber plantations.

The consequences social and political of this influx of workers is

touched on in my book. I believe one effect was the strong support the

parties of the Left – the LSSP and later the JVP – received in the

return of members to Parliament. Kalutara always appeared to return Left

or Left of centre parliamentarians more than those of more rightist

persuasion.

|