Role of transport in accelerated development

By Dr. Lauthasiri Gunaruwan

Part two

The Puzzle and the Solution

The challenge is therefore evident. On the one hand, the pressure on

the ports, customs, warehousing, roads, transportation and other

logistics related operations, in aligning with the imperatives of this

accelerated growth scenario would be quite significant, and a failure to

live up to expectation would put the entire growth process at risk. On

the other hand,

investment

requirements to develop transport infrastructure and logistics in view

of successfully meeting the demand would be quite substantial, and such

high levels of investment, funded through external borrowings, would be

unsustainable, and could drive the economy to instability. Either way,

the outcome would be undesirable. investment

requirements to develop transport infrastructure and logistics in view

of successfully meeting the demand would be quite substantial, and such

high levels of investment, funded through external borrowings, would be

unsustainable, and could drive the economy to instability. Either way,

the outcome would be undesirable.

Would it be strategically possible for the economy to find a way out

of this apparent ambivalence? The key to solve this puzzle is found in

capital productivity itself, where improved capital productivity would

reduce the degree of factor inputs needed to achieve a given output

target, both at aggregate and sectoral level.

Let us consider, for the sake of analysis, an improved overall

capital productivity scenario represented by an ICOR value lowered to

4.0. What would be the implications on the macroeconomic parameters?

The investment demand to achieve the 9% growth rate drops by 11%,

bringing the required investment ratio to more realistic, but still

ambitious, 36%. The resource gap thus drops to 9% from 14% under the

prevalent ICOR of 4.5.

The growth path thus becomes more sustainable as the long-term

effects of having to borrow to finance resource gap would be less. The

horizon becomes much more realistic and achievable.

This transpires into the transport sector as well. Reduced resource

gap would mean a comparatively lesser rate of growth of imports required

for a given rate of export growth.

The economy therefore would become less foreign trade intensive, and

the resultant total international trade growth over the five year

period, required to achieve the economic growth target of 9%, would be

little over 117%. This implies a reduced trade requirement in volume

terms of approximately 9% compared to 11% required under the ICOR of

4.5. The burden on ports and other trade-related transport and logistics

services would be eased to that extent, making the entire growth

scenario achievable in the ground level as well.

Capital Productivity: How to approach?

Enhancement

of capital productivity at the macro level pre-requires capital

efficiency gains in the level of individual sectors and industries.

Thus, the transport sector, securing a significant share of the State’s

capital resources, shoulders a special responsibility to be more

productive in its capital. Enhancement

of capital productivity at the macro level pre-requires capital

efficiency gains in the level of individual sectors and industries.

Thus, the transport sector, securing a significant share of the State’s

capital resources, shoulders a special responsibility to be more

productive in its capital.

Capital productivity improvement requires a long-term and persistent

strategic intervention to ensure (a) high productivity of new

investment, and (b) improved productivity of the existing capital stock.

The former is relatively easier as it is regarding decisions to be made.

The latter, however, concerns of decisions taken during bygone era, and

hence difficult to change.

This applies to all sectors of the economy. Making the existing

capital stock in the sector more productive, and exercising diligence in

planning and implementing transport related new investment, therefore

become extremely important if the transport sector is to realistically

shoulder the challenges of accelerated economic growth with less effort

and sacrifice.

Diligence in Capital Spending

What produces the value added is not the ‘expenditure’ made, but the

‘asset created’. Recorded in the national or sectoral statistics is

merely the expenditure incurred and not the qualitative and quantitative

measures of the accumulation of physical capital. Amounts of rupees or

dollars spent on a transport related project, therefore, would not mean

much unless such are fully and effectively deployed in creating a

productive asset. Any leakages in the process, inefficiencies or

over-expenditures, thus, lead to a gap between the expenditure made and

the value of output generated. As the creation of future value added

depends on the capacity of capital assets generated and not on the

expenditure made on them, such gaps will inevitably give rise to poorer

implicit investment productivity estimates, or higher ICOR values.

Investment appraisal, a vital exercise undertaken prior to making

investment decision, helps ensure productivity of new investment. In the

case of investments made by the private sector, a financial viability

assessment is imperative in investment decision making, as the purpose

of investment would be profits.

Thus, the capital productivity in private sector projects is

automatically taken care of. Such a natural compulsion does not exist

with regard to State sector projects mainly because the decision-makers

are aware that they are not at financial risk of any losses incurred

owing to implementing an unviable investment. Therefore, explicit

measures and procedures are required to ensure that public sector

investment decisions are based on a proper assessment of their

socio-economic viability.

Calling for competitive bids for procurement based on pre-determined

specifications helps capital efficiency as the procurer would then have

the choice of going for the most productive alternative. This

opportunity is absent when unsolicited offers are entertained with no

competition, and the possibility of over-estimated capital expenditure

cannot be ruled out under such circumstances. Extra care is thereby

necessary to ensure that the quoted investment figures are reasonable

and not excessive.

An

increasingly large proportion of projects implemented in the transport

sector appear to be from unsolicited offers where only a single proposal

is available for appraisal. To that extent, the role of planning becomes

more important to ensure capital productivity of new investment. An

increasingly large proportion of projects implemented in the transport

sector appear to be from unsolicited offers where only a single proposal

is available for appraisal. To that extent, the role of planning becomes

more important to ensure capital productivity of new investment.

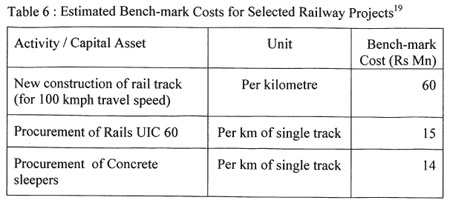

Bench-marking capital investment could be useful for planners and

policy-makers in minimising the possibility of incurring excessive

capital expenditure in public sector projects, particularly when

competitive bidding procedure is not adopted.

The key is to acquire the required quantum of a capital asset of a

pre-determined quality at the lowest possible capital expenditure.

Higher than acceptable ICOR levels indicate that this requirement has

not been sufficiently met, and that there is scope for improvement in

future investment decision-making.

Effective usage of capital assets

Creation of a capital asset with the required efficiency is not a

sufficient condition to ensure the generation of the expected growth

impetus. Its deployment and effective use in its intended purpose are

also imperative. Any asset created through capital expenditure, but not

effectively used, amounts to a waste.

There are, unfortunately, a number of such unused or poorly used

capital assets in the transportation sector. Kelaniya new railway bridge

still unused even after five years of its completion at a cost of Rs.

950 Mn. Nilwala Ganga railway bride, completed in 2007 at a cost of Rs.

320 Mn is suffering the same fate.

It took nearly seven years since completion in 2001 to put the

Mattakkuliya road bridge, constructed at a cost of Rs. 240 Mn, into full

use. Kelanisiri road bridge, Japansese funded Load Testing Plant at

Ratmalana railway workshop and the new facility to rebuild railway

carriages at Dematagoda, are among other examples of investment in

capital assets which lie idle.

Poor conception of projects, inadequate planning, delays in

associated sub-projects, or simple abandonment owing to change in

political or administrative leadership are commonly perceived causes.

Whichever the case may be, their avoidance would help improve capital

productivity in the transport sector, thus enhancing the growth impetus

of transport sector investments.

Operational efficiency

Assets so created with capital efficiency, and put into use, need to

be properly managed to deliver economic benefits. Efficacy of planning

and implementing projects would become futile if they are improperly

operated and managed in producing services.

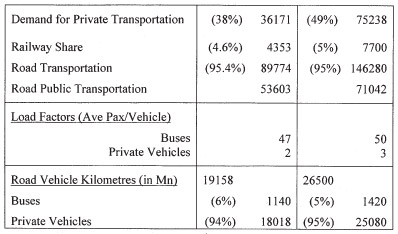

Properly deployed and managed capital assets would generate value to

the optimum levels, thus reducing the pressure on infrastructure and

other capital assets to expand unnecessarily. Operation of public buses

and trains at reasonable load factors, for example, would help transport

sector enhance its capital productivity, thus enabling the sector to

satisfactorily support economic development process with the smallest

possible rolling-stock fleet.

The market today is much more competitive than a few decades ago. It

requires a broader spectrum of qualitative parameters, including

punctuality, standards, comfort and speed, in addition to traditionally

expected connectivity and mobility at affordable costs, to attract

customers.

Unlike a few decades ago, the customers have a wider choice open to

them, and their affordability levels of costlier alternatives have

increased.

Thus,

the public transport sector and its operators will have to look beyond

the current horizon, and reform themselves to face the evolving demand

conditions, if satisfactory patronage of the services they offer is to

be expected. Thus,

the public transport sector and its operators will have to look beyond

the current horizon, and reform themselves to face the evolving demand

conditions, if satisfactory patronage of the services they offer is to

be expected.

Railway service, for example, would continue to lose its passenger

market share unless it is reformed to become more customer oriented, and

capitalise on its comparative advantages in providing long distance

services of quality with shorter travel times, and commuter services

with more capacity, reliability and punctuality. Intercity express

operation, if properly planned, pitched and marketed, is likely to fetch

demand. Attention of policy-makers should be drawn to explore this

possibility as without greater patronage of railway by passengers and

freight customers, the transport sector would not only become incapable

of supporting economic development, but also will become a retardant of

development process through wide-spread generation of negative

externalities.

Minimising growth-destructive effects

Managing externalities is another parameter of strategic importance.

This is because the negative externalities of transport sector, expected

to be generated in much larger proportions owing to the demand-pull

growth of transport-related activities, could, in return, become growth

destructive. For example, the growth of private vehicle fleet by 40% in

5 years, expected under a high economic growth scenario, would cause

severe pollution, congestion, and accidents.

This could undermine the growth and development process through

negative social and economic implications. It would be the urban poor

who would be exposed and most affected from such externalities.

Fuel consumption would go up in parallel to the vehicle kilometres

operated, and a significant proportion of such costs would be borne by

the general public to the extent that fuel would be priced below true

costs.

Offering road space free for motorists is a social injustice because

it would be the rich who would benefit at the cost of welfare of the

poor, Furthermore, our motorists do not efficiently utilise the scarce

road space provided free of charge for them.

The result would be operational inefficiency, thus calling for

structural adjustment within the transport sector in favour of public

transportation.

Hence, not only the diligence in capital spending, but also

minimising wastages, leakages and over-expenditures, as well as proper

planning of capital projects to avoid idling or under-utilisation of

assets, become imperative.

It is necessary to maximise operational efficiency and minimise

negative externalities. These are essential requirements for the

transport sector to better serve as an effective “load bearer” of

national economic development in the medium to long run.

Exploiting investment beyond Capital Accumulation

It is the conventional role of investment, namely, the building up of

the capital stock, which has largely been played in the transport sector

in the recent past. Investment has been made for the purpose of capital

accumulation, in view of ensuring future productive capacity in the

sector. A bridge or a train or a signalling system has been looked upon

merely as a required capital asset to operate trains, and hence to

produce transportation benefits. Little appears to have been done to

think beyond this traditional horizon.

Yet, the capital expenditure could stimulate another economic spiral

through its “demand creation effect”, potentially much wider than what

is fuelled by the “asset creation effect”. A capital expenditure made

has the potential of multiplying its income generation effects over and

over again when such expenditure is ploughed back into the national

economy . A marginal propensity to consume of 0.75, for example,

provides for a multiplier of 4, meaning the theoretical possibility of

securing four times the investment value as economic benefits over the

years, in addition to the value generated through usage of the asset.

For this, investment programs need strategic formulation.

Projects have to be developed in such a manner that the domestic

economic forces would be used to the maximum possible extent in creating

assets so that the value addition, in the process of asset creation,

would accrue to the national economy. Projects executed by foreign

agencies, for example, would add less value within the local economy,

depriving the local enterprise of possible opportunity to earn, grow and

further invest in the economy.

Trends observed in the recent past

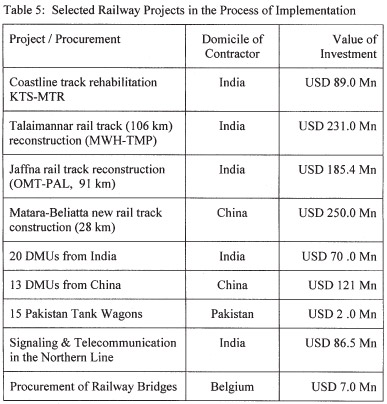

Let us take the example of railway track construction in Sri Lanka.

Historically the job was done locally, by the Sri Lanka Railways, using

material inputs from abroad when such could not be sourced locally.

Even for the procurement of material, the competitive bidding

procedure was adopted by and large, resulting in cost effectiveness in

inputs. The technology unavailable with us was obtained through

procurement at competitive prices.

The projects were thus implemented in achieving both benefits, namely

(a) construction of the asset (in this case the railway line) to

generate value addition in train operation, and (b) creation of linkages

to the maximum possible extent within the local economy through which

“construction related” value added, and many other multiplied economic

value generation spirals, would be stimulated.

The recent pride of Sri Lanka Railways, in this regard, was the

reconstruction of over 60 km and damage repair of another 40 km of the

Tsunami affected Coastal railway line in 56 days in early 2005,

exclusively by local effort, at an estimated cost of Rs 450 Mn.

When the contracts for railway track construction are granted to

foreign companies, a greater proportion of value generated in

construction would be accrued outside the national economy. Such

investment would only be initiating one of the two possible economic

growth effects, namely the “asset creation effect”. It would fail to

initiate construction demand-related multipliers, thus, depriving the

economy and its stakeholders a significant portion of growth potential

of capital expenditure incurred. The sub-optimality would be more if the

cost of construction by foreign sources becomes much greater than the

local estimates.

Execution of projects and the impact on GNP

The Gross National Product (GNP) differs from the commonly used Gross

Domestic Product (GDP) by the amount of net factor income from abroad.

Factor incomes earned and repatriated by non-national economic agents

operating on Sri Lankan soil are excluded from the GDP, and the factor

incomes earned by Sri Lankan entities operating abroad and remitted to

Sri Lanka are added, in order to compute GNP. Therefore, the evolution

of GNP as a ratio of GDP could reflect as to how favourable or adverse

the trend of Sri Lanka’s net factor income flow has been.

The GNP/GDP ratio of the Sri Lankan economy, worked out in current

market prices, displays a significant downward trend over the past 25

years.

This indicates a growing net repatriation of factor returns as a

ratio of GDP. In other words, the inflow of factor earnings from abroad

is increasingly becoming insufficient to compensate for the outflows.

This observation is relevant for our discussion because much of this

may be largely “investment centred”. Higher the foreign capital borrowed

for domestic capital formation, and more the contracts for road,

railroad, port or airport construction in Sri Lanka are undertaken by

foreign enterprises, greater would be the outflows of factor returns on

account of interest, wages and profits. This would lead to deterioration

of GNP/GDP ratio unless the inflow of factor returns does not grow at a

sufficiently high rate to compensate for the growth of outward

remittances.

There exists a notable difference between Foreign Direct Investment

and public sector infrastructure investment executed through foreign

contractors. In the case of FDI, the company would source capital, bears

investment risks, becomes responsible all factor payments, and takes

away only a portion of what it would generate as domestic value added.

The Government becomes the investor in the case of the latter, and

responsible for making outbound interest payments on foreign borrowed

capital, irrespective of the project’s viability. The Government would

also bear the risk of generating value added on the investment made, but

pay in full to the foreign contractor for the project execution. Foreign

lenders and foreign contractors would wish to maximise deployment of

material, labour and technology of their country of origin.

Thus, the possibility of such undertakings withdraw almost everything

they generate as value through their activities, and leave hardly

anything for the local economy other than the asset created, cannot be

excluded.

Making contractual opportunities for project execution available for

local entrepreneurship wherever possible, feasible and capital

efficient, therefore, will help reduce the foreign dependence in

investment, prevent shrinkage of GNP as against GDP, and enhance

domestic capacity building and resource employment.

Foreign enterprises should be employed to execute public investment

contracts only when such involvement becomes essential and unavoidable.

When employed, the policy-makers should be smart enough to secure

maximum possible returns to the local economy by way of strategically

managing such foreign loan packages and projects.

The transport sector, including Highways, Ports and Aviation, has

made commitments on capital expenditure of nearly USD 6 Bn on

infrastructure development through foreign borrowings during the past

six years. This trend is likely to continue.

Therefore, the transport sector bears a considerable responsibility

to strategically meeting this challenge by making available the

investment opportunities arising out of development needs to the local

enterprises and organisations with priority and to the maximum possible

extent, for the betterment of our national economy.

To be continued

|