Question of identity, a Buddhist perspective

By Lionel WIJESIRI

Have you ever wondered: “Who am I?” If you have, you are not the only

one, most people have. However, they think they just don't have the time

to find the answer or don't know where to look.

|

|

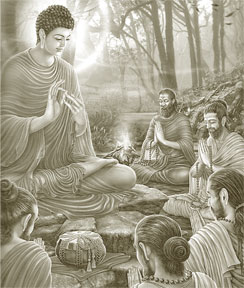

The Buddha preached the Anatta

Lakkhana sutta to the five ascetics |

The simple question seems easy to answer at first. Yet, as soon as

you start to think about it you realise that your name or a description

of your physical appearance is woefully inadequate to describe the

myriad of thoughts, moods, actions and reactions that make yourself.

Even a description of what you do becomes confusing because every day

you play so many different roles. The simple question seems easy to answer at first. Yet, as soon as

you start to think about it you realise that your name or a description

of your physical appearance is woefully inadequate to describe the

myriad of thoughts, moods, actions and reactions that make yourself.

Even a description of what you do becomes confusing because every day

you play so many different roles.

You start the day maybe as a wife or a husband, then at work you

become a clerk or an executive or a teacher, at lunch you meet a friend,

in the evening an acquaintance. In each role that you play, a different

facet of your personality emerges.

Sometimes you feel that you have to play so many different and

opposing roles that you no longer know what sort of person you are. When

you meet your boss at a party or your parents and friends come round at

the same time, you become confused as to how to behave.

Not only have you fixed yourself a special way of acting towards

them, but in your mind you have also limited them to a certain role. You

can relate to them as ‘your boss’ or ‘your parents’, not simply as

another human being. Yet you are quite aware that your real identity is

not defined by the role you play. Anatta Buddhist teachings take the

question of identity to an entirely different realm.

Anatta concept

The Buddhist concept of Anatta provides deeper understanding to what

constitutes a living or non-living being. People are often perplexed by

the Buddha’s teaching of Anatta, or not-self. One reason is because in

different religions and schools of psychotherapy and philosophy, as well

as in everyday language, the word “self” is used in many ways.

The Buddha clearly did not accept any metaphysical definitions of

“self”. On the other hand, he emphasised the suffering that can come

with clinging to anything as belonging to or defining “myself”. The

Buddha’s path of practice leads to the ending of this clinging.

The most common metaphysical “self” against which the Buddha was

arguing is implicitly defined in his Anatta Lakkhana Sutta - the

Discourse on Anatta. For something to be Atta, according to this view,

it needed three components.

It had to have complete control over the body, feelings, thoughts,

impulses, intentions, consciousness or perceptions. It had to be

permanent. And it had to be blissful. In this discourse, the Buddha

makes it clear that nothing in our psycho-physical experience has these

three qualities and is therefore fit to be regarded as an Atta or self.

The Buddha’s teaching shows us a way from looking for the self, or

trying to understand or improve the self. Instead it suggests that we

pay attention to the fear, desire, ambition and clinging that motivate

the building of self-identity.

|

|

|

Meditation and contemplation help

develop insight into the teachings on Anatta |

Perhaps we feel that we are defective in some way, and that our

meditation practice will help us make or find a better self. Can we

instead find the particular suffering that is connected with wanting to

improve the self?

Enlightenment

Enlightenment entails releasing our suffering, not avoiding it,

seeking relief from it or compensating for it. Dependent Origination

(The sense of identity) could be explained with the example of the

oyster and the pearl.

The identity is something that is created from the moment of

conception in much the same way a pearl is created in an oyster. There

is the initial grain of sand that irritates and slowly, but surely, it

is grown until we have something we feel is precious.

The initial starting “grain of sand” is our ignorance. The Buddha

explains this in the Law of Dependent Origination (Paticca-samuppada),

but in a more mundane explanation, as we come into being and become

aware there is a need to interact with the world.

The first step of “I” comes from survival: where am I? What is it my

senses are experiencing? How does the form I seem to be controlling

relate to the forms that appear independent from this body? The first

step of identity comes from a sense of cognition “this is the body and

that is not the body”.

As children we are taught “this is yours” and “this is mine”. The

idea of possession comes into being as we learn how to cohabit with

others. The concept of possession strengthens our sense of identity and

our relationship with the world. It gives structure for survival

socially and literally.

This identity also creates a more comfortable reference point to

navigate from as well, so we value these layers on our “ego pearl”.

When we create a sense of possession, we also concrete our

understanding of form. Objects must be unique and independent if they

are to be owned. Seeing the world as independent objects, we logically

see ourselves as independent as well. There is great comfort of

believing in the concept of “self”. It has been a very useful tool, and

the more energy given to the “self” or “ego” creates a greater sense of

safety and assurance.

Neurosis

By contrast, the idea of “no ego” is unsettling. Worse, the value

given to our identity becomes so fundamental to how we relate to the

world, that the idea of it not existing creates deep neurosis and

uncontrollable fear. The oyster’s response is to protect that “me”

concept in more layers. The pearl gets bigger and stronger. The final

layer of our “ego pearl” is the transformation of “I”. At first, the “I”

was a grain of sand placed as a reference marker.

Through ignorance and rationality, that sand transformed into

something that is perceived to be important, then essential, than

indestructible: the “ego pearl” is valued so highly by us that it must

have purpose. “I am special. The world around me happens to help or

hinder my destiny”. The layer of ego has now gone beyond the pearl. The

oyster now exists because of the pearl, not the other way around.

|

|

Identity is created from the moment of

conception in the same way a pearl is created in an oyster |

The value of a pearl is dependent on how much someone craves to own

it. This thirst (thanha) is the unwholesome craving the Buddha speaks of

in the Four Noble Truths. To see it as valuable, we hold on to it

tightly. It consumes our attention. When we travel, we protect it,

always worrying that it may be taken away.

It gives us stress as we avoid anything that threatens it, and cling

to it so tightly we find our hands and minds unable to engage fully. On

inspection, the pearl is just a bit of valueless sand and spit.

“Who am I?” is one of those wrongly formed questions. This is an

inquiry that many people in the world follow. However, a little bit of

reflection should make it very clear that this question already implies

an assumption that you are someone. It already implies an answer.

It's not open enough. Instead, one needs to rephrase the question

from, “Who am I?” or even, “What am I?” to, “What do I take myself to

be?” or, “What do I assume this thing called ‘I’ is?”

Such questions dig very deep into one's avijja (delusion). Only then

can one start to really look at what it is that one takes one's ‘self’

to be. It's through a combination of meditation and contemplation of the

five aggregates that we can develop the insight into the teachings on

Anatta that's beyond mere speculation, and rests instead within the

realm of direct experience.

|