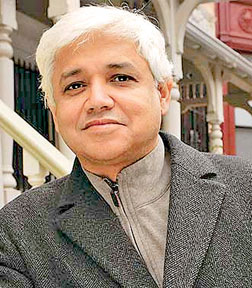

Amitav Ghosh’s tangled paths of modernity

Ghosh’s chosen medium is English; There are many South Asian writers

whose language of choice is English. Broadly speaking there are two

groups of writers outside the Anglo-Saxon domain who write in English. Ghosh’s chosen medium is English; There are many South Asian writers

whose language of choice is English. Broadly speaking there are two

groups of writers outside the Anglo-Saxon domain who write in English.

The first group would like to subvert the English language from

within. Raja Rao, drawing on Kannada and Sanskrit idioms, G.V. Desani in

hybrids forms of English, Salman Rushdie with his playful multiple

verbal registers belong to the first category. R.K, Narayan, Rohinton

Mistry, Vikram Seth, Amit Chaudhuri would like to extend the range of

English as an expressive medium through deft manipulation of

tonalilties. Amitav Ghosh belongs to this second category.

Salman Rushdie, initially called for the de-colonisation of English

and subvert it from within.

|

Amitav Ghosh |

Later, he somewhat softened his stance when he claimed that, ‘as for

myself, I don’t think it is always necessary to take up the

anti-colonial – or is it post-colonial?- cudgels against English.

What seems to me to be happening is that those peoples who were once

colonised by the language are now rapidly remaking it, domesticating it,

becoming more and more relaxed about the way they use it – assisted by

the English language’s enormous flexibility and size, they are carving

out large territories for themselves within its frontiers.’

Careful writer

Amitav Ghosh, surely, would endorse this claim. Ghosh is a careful

writer whose powers of description reveal his deep intimacy with the

language.

The following representative passage is taken from his novel The

Glass Palace. The village stood just above a sandy shelf where a chaung

had strayed into a broad meandering curve.

The stream was shallow here, spread thin upon a pebbled bed, and

through most of the year the water rose only to knee-height – a perfect

depth for the villagers’ children, whoa patrolled it through the day

with small crossbows. The stream was filled with easy pre, silver-backed

fish that circled in the shallows, dazed by the sudden change in the

water’s speed.

The resident population of Huay Zedi was largely female; through most

of the year the village’s able-bodied males, from the age of twelve,

were away at one teak camp or another up on the slopes of the mountain.’

Here the physical sense of place is caught in his precise language.

Language

Speaking of Amitav Ghosh’s controlled use of language, I wish to

focus on another interesting aspect – what I would like to refer to as

his use of idea-images. What I mean by this is his ability to fuse

thought and description, reflection and visuality into images. Here

ideas feed the imagination, and in turn, the imagination feeds ideas.

This is indeed a feature that characterises the some of the greatest

novelists such as Leo Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, George Eliot, Joseph Conrad,

Thomas Mann and J.M. Coetzee. It seems to me that Ghosh is seeking to

move in that direction.

A passage like the following taken from his novel The Shadow Lines

illustrates this point.

‘But despite that, I could not still believe in the truth of what I

did see; the gold-green trees, the old lady walking her Pekinese, the

children who darted out of a house and ran to the postbox at the corner,

their cries hanging like thistles in the autumn air.

I could see all of that, and yet, despite the clear testimony of my

eyes, it seemed to me still that Tridib had shown me something truer

about Solent Road a long time ago in Calcutta, something I could not

have seen had I waited at that corner for years – just as one may watch

a tree for months and yet know nothing at all about it if one happens to

miss that one week when it bursts into bloom.’

There is an interesting fusion of visual observation and

self-reflection. It seems to me that the function of idea-images is

precisely to enforce this two-way interaction.

What this short description does is not only deepen our understanding

of the enigmatic Tridib but also offer a glimpse into the unfolding

sensibility of the narrator.

The same features can be discerned in the following passage.

And still, I knew that the sights Tridib saw in his imagination were

infinitely more detailed, more precise than anything I would ever see.

He said to me once that one could never know anything except through

desire, real desire, which was not the same thing as greed or lust; a

pure, painful, and primitive desire, a longing for everything that was

not in oneself, a torment of the flesh, that carried one beyond the

limits of one’s mind to other places, and even, if one were lucky, to a

place where there was no border between oneself and one’s image in the

mirror.’

Here again, we see how the idea-image works deepening out awareness.

So far I have been discussing the ways in which we as Sri Lankan writers

and critics can learn from the example of Amitav Ghosh.

But as I intimated earlier, he has his share of blind spots and

deficiencies. In a negative way, these too can prove to be instructive.

Many of the experiences explored in his novels can be usefully

connected to, and encompassed in, the concept of modernity, or to be

more specific cultural modernity. He raises a number of issues related

to cultural modernity in India and elsewhere.

While this effort needs to be commended, it has also to be stated

that he does not pursue adequately the political and ideological

implications of the problematic issues he raises whether they relate to

the production and implementation of scientific knowledge or the

collusions of nationalism and communalism. In other words, the political

and ideological coordinates of his privileged issues are not legibly

mapped.

Writers in Sri Lanka, too, are concerned with the kind of social

issues that Amitav Ghosh has raised in his fiction. If we examine the

growth of the Sinhala novel from Piyadasa Sirisena onwards we would most

certainly perceive diverse attempts to grapple with some of the selfsame

issues. In most cases, these issues are not framed in theoretically

persuasive terms.

Ghosh too fails to meet this requirement by not paying adequate

attention to their political and ideological concomitants.

So, his failure should prompt us to think afresh the various social

issues connected to cultural modernity and how they can be framed better

and comprehended more productively by paying closer attention to their

political and ideological implications.

What I have sought to do in these columns on Amitav Ghosh is to

explain briefly the nature and significance of his body of writing to

date, identify his strengths and weaknesses, and to point out aspects of

his work that could prove to be instructive to us in Sri Lanka. He is

certainly a thoughtful writer who merits close study. And one can safely

predict that his best work is yet to come.

|