Ulysses and language

James Joyce’s Ulysses is a seminal literary production in the 20th

century on many counts. One among many is the author’s playing of the

language.

As observed by Declan Kiberd, Joyce has used language not merely as a

mood of expression but also as a means to achieve diverse objectives.

For instance, Joyce effectively uses language to extend the self-mockery

or self-critical aspect of the novel.

Kiberd says, “That mockery extends even to the notion of written word

itself. ‘Who ever anywhere will read these written words?’ asks Stephen

Dedalus, in what may be one of the few lines written by Joyce with a

complete straight face. He foresaw that the written word was doomed to

decline in an age of electronic communication (which he himself had

helped to usher in by opening one of the first cinemas in Dublin).

|

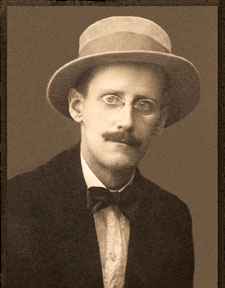

James Joyce |

This was yet another reason why he chose to base his work on a Greek

legend which was told in oral narrative long before it was committed to

writing. It was the fact that the words had to be written which bothered

Joyce, who fretted over all that was lost in the transition from ether

to paper. He myself would have preferred a musical to a literary career,

and his works all gain greatly from being read loud. For example, in the

Nausicaa chapter, Bloom’s ecstasy at the sight of Gerty MacDowell’s legs

is captured by a rising crescendo of ‘O’ sounds, after which she walks

away, prompting him to ponder. “

One of the reasons which prompted Joyce to experiment with language

is that he was dissatisfied with ‘previously writerly styles’. Kiberd

observes, “Ulysses, therefore, pronounced itself dissatisfied with

previously writerly styles, offering pastiches of many, especially in

the Oxen of the Sun chapter, in order to clear the way for a return to

oral tradition with Molly Bloom. (This is one possible meaning of the

massive full-stop at the close of the penultimate chapter.) By

incorporating within its self-critical structure a sense of its possible

obsolescence in a post-literate world, Ulysses is at once the

consummation and the death knell of the age of print. In that respect

too, it is very much of its time.

When a concerned friend told Picasso that the cut-price canvas on

which he worked would be rotting fifty years later, the artist simply

shrugged and said that by then paintings would have cease to matter. The

post modern novel is now conceding, if not its absurdity, then its

limited durability. If nervous authorial interventions marked the

novel’s beginnings as a literary form, they may also signal its end.”

Distrust of written English

Kiberd points out from the very beginning Joyce’s distrust the

written English and that distrust is, in a way, predictable partly due

to Joyce’s upbringing in a linguistic environment which was dominated by

‘oral culture’ and partly , it was due to ‘loss of native language’; “

Joyce’s distrust of written English might have been predicted of a man

who grew up in an essentially oral culture, but it had its source in his

sense of trauma at the loss, in most parts of Ireland through the

nineteenth century, of the native language. The fate of a sullen

peasantry left floundering between two languages haunts the famous diary

entry by Stephen Dedalus in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.”

In A Portrait, Kiberd says that Joyce would have been mocking ‘the

widespread hopes of a language revival’ and he is also not ‘fully happy

about the English-speaking Ireland of the present.’ Kiberd also notes

that Joyce expressed his dissatisfaction of the fact that ‘English did

not provide a comprehensive expressive ensemble for Irish people

either’.

“This is part of the tragicomedy of non-communication pondered by

Stephen during a conversation with the Englishman who is dean of studies

at his university; ‘The language in which we are speaking is his before

is mine. How different are the words home, Christ, ale, master, on his

lips and mine! I cannot speak or write these words without unrest of

spirit. His language, so familiar and so foreign, will always be for me

an acquired speech. I have not made or accepted its words. My voice

holds them at bay. My soul frets in the shadow of his language.”

Irish writers

Kiberd notes that ‘Joyce found himself probing its limits’; “Living,

like other Irish writers, at a certain angle to the English literary

tradition, he could use it without superstition, irreverently, even

insolently.”

Kiberd observes that words in Ulysses have been used in a manner to

‘reveal and to conceal’: “The interior monologues of Ulysses permitted

Joyce to contrast the richness of a man’s imaginative life with the

poverty of this social intercourse. Compared with the tour de force

monologues, the recorded conversations are mostly unsatisfactory, a

bleak illustration of Oscar Wild’s witticism that everybody is good

until they learn how to talk.

Words in Ulysses are spoken as often to conceal as to reveal. The

deepest feelings are seldom shared, and usually experienced by isolates.

Bloom never does forgive his wife’s infidelity in an exchange of words,

as he has already forgiven her in her mind. Joyce critically explores

the equality of conversation among Irish men in groups, finding them

fluent but all too seldom articulate. It goes without saying that they

go without saying what is true on their minds. They are as inarticulate

in the face of Bloom as he will later be in the presence of Stephen and

Molly. Only in solitude does Bloom scale poetic heights.

Yet unlike other men, Bloom shows redemptive awareness of his own

inarticulacy. He feels a real empathy with all dumb things. Kind of

animals, he tries to translate the household cat’s sounds into human

words like ‘Mekgnao’ or ‘Gurrhr’. The machine in the Newspaper office is

‘doing its level best so speak’ and so, frantically, he coins the word

‘sllt’ to render its sound. Like his creator, Bloom too is seeking to

extend the limits of language, so that it can encompass signals from

previously inarticulate world. His sympathies with human flow naturally

to those as lonely as himself; and such encounters, as with Gerty

MacDowell, are often wordless, conducted in the language of the body. ” |