|

Leopard tales from the past:

The leopard that got away

By Jayantha Jayawardene

[Part 3]

Continued from last week

Below are two translations from two reports of how a leopard kills

its prey. These were reports made by a Game Guard and a Game watcher and

appeared in the Wildlife Warden's Report of 1954.

"I was on my way to Yala one evening and, near Wilapalawewa, I

noticed a leopard lying beneath a tree. I took cover and watched. The

leopard was lying on its belly with its forelegs stretched forward and

its gaze was fixed on a herd of spotted deer which was grazing about 100

yards away. It kept tossing its tail about but its head and body were

motionless. The unsuspecting deer were nibbling the grass and moving

slowly forward towards the leopard...

As they approached closer and closer the leopard gradually brought

its forelegs back closer to its body and kept its head low down, but the

occasional twitching of the tail continued.

When the deer were within 20 yards the leopard became very tense and

I knew that the charge was imminent. Suddenly, it shot forward like a

streak and in a flash had seized a spotted doe.

|

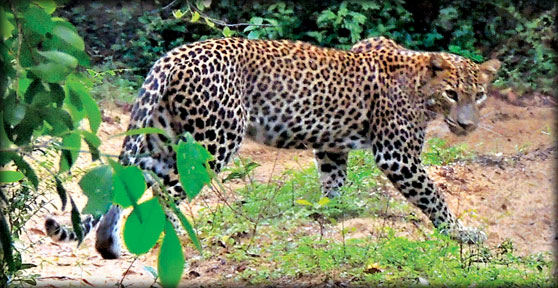

A leopard in Wilpattu Pic: Indika Edirisinghe |

It attacked the doe from in front and, threw its paws round the doe's

neck, seized the doe by the throat with its jaws and clung on.

The rest of the herd ran some yards and then stopped and stood

looking on, barking and stamping. The doomed doe stood its ground for

some minutes while the leopard hung on and got its fangs deeper into its

victim's throat.

Doe

Then the doe collapsed and fell sideways. The leopard did not relax

its hold but pressed the doe, which was kicking and making frantic

efforts to rise, to the ground. Soon the doe lay still.

The leopard then released its hold, moved off a few yards, sat on its

haunches and looked at its fallen victim. Two or three times it sprang

back on the doe and bit its neck, and again moved away and watched.

Then the leopard seized the carcass of the doe by its neck, and

dragged it, the carcass being parallel to the leopards body, towards the

tank. The herd of deer, which all the time remained 30 or 40 yards away,

followed the leopard at a distance, still giving the shrill alarm call"

- W.L.A. Andris, Game Guard, Yala Range.

"At about 7 o' clock in the morning, at the height of the drought, I

saw a leopard about 150 yards away walking across the bed of the

Maradanmaduwa tank. I followed cautiously, got under a tree and sat down

to watch. The leopard by then had climbed up a Dan tree and lay down on

branch about 10 feet above the ground. The Dan tree was in full fruit

and every day deer and pigs used to come under it to eat the fallen

berries.

The leopard lay perfectly still on the branch of the tree, only

turning its head to look all around. After about half an hour a small

herd of nine spotted deer came across the dry bed of the tank, stopping

to nibble every now and again, towards the Dan tree. The leopard became

absolutely still. The deer reached the tree and began to feed on the

fallen fruit.

One of the does came right under the branch on which the leopard was

lying. I saw no movement of the leopard which was absolutely still and

tense. Suddenly it sprang on the back of the doe beneath it.

The doe called out loudly but the leopard kept its hold and bit at

the doe's throat, with each bite getting a firmer grip on its throat. At

the doe's cries the rest of the herd stampeded for a short distance and

then stood and barked violently and stamped the ground with their

forefeet.

Claw

The seized doe then fell to the ground. The leopard continued to bite

the fallen doe's throat and to claw its body, the leopard's tail

twitching and tossing from side to side all the time. The doe soon lay

still and the leopard got off its kill, moved away two or three yards

and sat on its haunches, panting and watching its kill. It sat thus for

about two minutes and then got up and walked twice round the dead doe.

Then it urinated and scattered the earth with its hind feet and came

back to the carcase. It seized the carcase by the neck, and walking

backwards, dragged the carcase about 20 yards into scrub jungle and

disappeared from view" - A. Malhamy, Game Watcher, Wilpattu Range.

Referring to the manner in which a leopard kills its prey, Baker

(1855) says that "The blow from the paw is nevertheless immensely

powerful, and at one stroke will rip open a bullock like a knife; but

the after effects of the wound are still more to be dreaded than the

force of the stroke. There is a peculiar poison in the claw, which is

highly dangerous.

"This is caused by the putrid flesh which they are constantly

tearing, and which is apt to cause gangrene by inoculation".

Rex La Brooy, writing in the Loris (Volume VII No 5) states: "It is

indeed rarely that a man can come into head-on collision with an angry

leopard and survive sufficiently long to narrate his experiences.

Such has been my fortune, and, as I write this now, I can see those

bared snarling teeth, the small ears flattened against the head, the

tiny beady eyes just before mine, and in my nostrils is the smell, that

awful nauseating smell of putrefying flesh coming from the leopard's

mouth, so overpowering that even after I was carried away from the spot

the stench remained around me.

I have no desire to repeat that experience. But let me begin at the

beginning. Four of us, Ray de Costa, Malcolm Felsianes and Hugo

Bilsborough and I decided that a "safari" in the jungles of South-East

Ceylon was indicated. The July drought was at its most intense, when we

left Colombo well-armed, as we thought, with still and cine cameras.

"The next day found us travelling through parched plains over which

the 'Kachan' blew raising dust storms that not only made us

uncomfortable but reduced visibility to only a few yards.

Dusk was setting in as we drove on. In the distance, something

crossed the road. It looked like a large boar or a leopard. We drove on

and stopped at the spot where the unidentified animal had entered the

jungle. There was nothing on either side of the road except park-land

with one large bush about ten yards away from the road, and a few small

dried almost leafless bushes here and there.

Branch

After a few minutes spent in discussing what the animal could have

been, I stepped out of the car and walked up to the bush, and round it,

looking carefully at every dried leaf and branch. As I walked round, I

heard a rustling within the bush.

Immediately I tensed and peered cautiously beyond the outer branches

into the bush itself. It was virtually impossible to see a leopard

hiding inside a bush. Nature's camouflage is perfect. All I saw was the

bush.

The next thing I saw was the bush come to life. Then a blur and for

an instant a hazy image of an angry cat, teeth bared, ears flat against

its head, pugs extended.

Years of conditioning and years spent in the jungle, have given me

quick reflexes, and with an animal-like instinct I swerved away from the

charging mass of feline lightening. But my movements were slow when

compared to what flew out of that bush with the velocity of a bullet.

As the blackness engulfed me I heard the deep-throated growl that

rose to a crescendo and died away.

As I went down, my last instinctive movement saved my life. The

impact of the animal hitting my right shoulder swung me round and I

dropped to the ground as the leopard, carried by the momentum of its

charge, went over me, to bound away into the jungle a few yards away

from the bush. The growls of the angry beast could still be heard as my

companions, armed with only a stick rushed out of the car to where I

lay. While Hugo stood by with a pathetic apology for a club, Ray and

Malcolm picked me up and carried me over to the car.

At the provincial hospital, which they reached in a matter of minutes

breaking all records for speed on those roads, I woke up with a sharp

pain in my shoulder. On my forehead was a bump, bigger than a golf ball

where the leopard's head had struck me. Under my blood-soaked shirt, on

my arm and shoulder were no less than nine claw and teeth marks.

The next morning we went back to the scene of our escapade. This time

we had a better weapon than a camera.

We had a starting handle of a car! We wanted something more than

pictures. We wanted measurements and a motive as to why the leopard

behaved in the way he did. Had we disturbed him at a meal? Was he a

man-eater?

We found no "kill" in the vicinity. No human had been killed by a

leopard in this area recently and there was no man-eater roaming the

wild. The pug marks indicated that the animal was a full grown male.

The experts of the area, whom we consulted later gave three reasons

for my good fortune in escaping. First, my instinctive turn-round which

carried me in a direction away from that of the charging leopard.

Second, the head-on-collision with the leopard, a rare experience

indeed, saved me, for I was knocked out like a light. Had I stirred

after my fall, the animal would have come for me again and with fatal

consequences.

And finally, the prompt action of my companions in rushing out of the

car must surely have scared away the already bewildered animal.

But why did the animal come out of the bush to attack me, when I had

no knowledge that it was there? All I could see was the bush. If it

wasn't hungry and if it wasn't disturbed from a kill and if it wasn't a

man-eater then why did it charge?

Perhaps the peculiar behaviour of the leopard in these circumstances

could be attributed to the drought. I still wonder why. Perhaps the

leopard roaming somewhere around in those jungles today, is wondering

why!"

To be continued |