|

DIY Culture festival:

The UK's fanzine scene remains a thriving subculture

Scrawl, cut, stick, print, fold, staple. It's a ritual for every

fanzine editor. Fanzines, for those without paper cuts, are

self-published magazines on subjects as varied as secret mischief caused

while temping, and personal insights into depression, as well as to odes

to Bruce Springsteen's elbows.

|

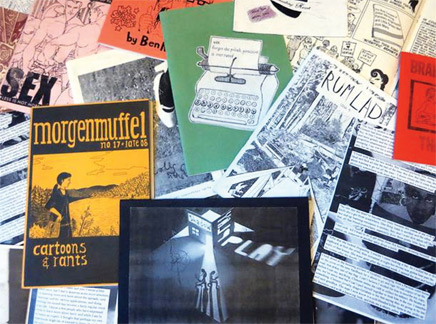

Cut and paste: a selection of a fanzine collection |

They emerged in the seventies in an inky-fingered protest by punks

against the mainstream and have been painstakingly crafted - and printed

off on work photocopiers while no one is looking - ever since.

Stall holders

Against the odds, the UK's zine scene remains a thriving subculture

in a world that has otherwise moved online.

This weekend, zinesters will be heading to DIY Cultures, an annual

fanzine festival in east London complete with zine-making workshops and

a jam-packed line up of stallholders. It comes soon after a similar

shindig in Sheffield and precedes the Dublin Zine Fair, taking place in

August.

On July 21, International Zine Library Day will see creators attempt

to write and publish new zines within 24 hours.

On the surface, the effort it takes to hand-craft and distribute

fanzines in the post might seem baffling when the process could be so

much quicker and cheaper online.

Why seek out a zine dedicated to your football club when you can get

live updates on Twitter? Why pick up a music zine when you can have a

quick swipe on to the Spotify app?

Aesthetics

Chella Quint, co-organiser of the Sheffield Zine Fest says: "Zines

are here to stay. People experience real pleasure and satisfaction from

holding something they've created and printed themselves, that they can

physically hand to someone." Isy Flynn, editor of established comic zine

Morgenmuffel, says: "I love what you can do with a paper zine.

The feel and the aesthetics, leafing through, reading it on the loo.

A magazine has an editor, a budget, ads and an agenda that includes

being focused on sales. A zine is just whatever its creator wants it to

be."

Buying and selling zines is now easier, with online payment tools and

stores such as PayPal and Etsy replacing old-school stamped, addressed

envelopes and ailing independent record shops.

Rum Lad creator Steve Larder insists that "there's a greater sense of

quality control in zine making, given the time and effort involved" than

there was in the pre-online era, when music news dominated zines. My own

music and musings zine, ShadowPlay launched in 2003, has led to spin-off

gigs, craft nights and thousands of touching letters and mix tapes

exchanged with zinesters worldwide.

Opinions are split over online's influence in zines, not least in

football.

Middlesbrough FC zine, Fly Me to the Moon, launched in 1988, has an

uncertain future now that social media increasingly dominates football

fandom. Editor Robert Nichols says: "I don't like the idea of putting

the fanzine online - for me, it should be something people buy at the

match and put in their pocket for future reading."

Other zines have found a new lease of life online. Sheffield

Wednesday zine War of the Monster Trucks has found a renewed fan base

since its digital rebirth in 2011. "Social media is much more alive and

flexible," says editor Steve Walmsley. "While we romanticise going back

to print, deep down we know we wouldn't do it."

Of course, the two aren't mutually exclusive. The comedic and chaotic

spirit of zines can still be felt online through high-profile sites such

as Vice and Buzzfeed. At the same time, attendance at zine fests has

grown as promoting them has become simpler online. There's even a

fanzine maker's social network, We Make Zines.

Fanzines are perhaps unlikely to return to being a news hub with

print runs in their thousands. But as an intimidate bond between writer

and reader, using an aesthetically pleasing avenue, they may just have

found their place in the 21st century.

- The Independent

|