|

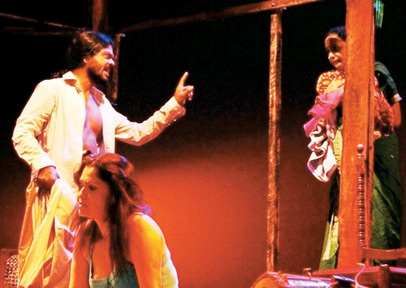

Scenes from the play |

Daasa Mallige Bungalawa:

Core of the play, no laughing matter

by Dilshan Boange

[Part 1]

When someone of unapologetic brashness and the unwavering conviction

of his self-righteousness says that ‘God cannot control our desires’,

one might wonder if it is outright blasphemy or a simple statement of

truth.

There was a great deal of potency in that particular line spoken in

Sinhala by Jayantha Muthuthanthri who played the lead role on July 23 at

the Lionel Wendt as ‘Stages Theatre Group’ brought to life Daasa Mallige

Bungalawa the Sinhala adaptation of ‘Sakharam Binder’ a Marathi play by

Indian playwright the late Vijay Tendulkar.

Directed by Ruwan Malith Peiris and Kalana Gunasekera, the production

seems to have a political objective in terms of how it builds a ‘social

critique’ of the plight of destitute women living in slums.

Although there was no objective of providing quality ‘entertainment’

and I wonder how much of the goal intended by the play was achieved.

It is not a comedy. It is a play with its moments of comedic spots

and dark comedy in certain respects. Therefore, its value as

entertainment per se must be looked at in relation to its own attributes

as a serious story.

What do people in Sri Lanka expect when they go to watch a stage

drama? For most, its entertainment of a more elevated nature as opposed

to watching a TV show at home or watching a movie.

Theatre, especially in terms of ‘the proscenium’, occupies that place

of being a ‘niche’, of being not for all and sundry. Entertainment,

therefore, to nearly every theatregoer here, must include moments ‘ripe

for laughter’ in the course of the performance. But what is at the core

of Daasa Mallige Bungalawa is no laughing matter.

Attributes

There was no clue whatsoever that the story’s origins are from

Maharashtra in India. For all intents and purposes Daasa Mallige

Bungalawa is a Sinhala play, fixed in a Sri Lankan scenario.

This speaks soundly of the skill and creative talents of the adapter,

the script being by S. Karunaratne. This is by no means a ‘translation’

of VT’s Marathi play, which has the protagonist as a book binder,

whereas the production by Stages Theatre Group had ‘Daasa’ as a local

fisherman living in a shanty.

From diction to the social setting to the mannerisms of the

characters there was not a shred of foreignness in the play. That

perhaps is why it can be disturbingly shocking when one watches it with

a more critically attuned eye.

The stagecraft in set design, lighting and audio factors were

tastefully executed and well suited for proscenium theatre.

But at one point Daasa’s hands were not tapping the sides of his drum

although the music produced from his drumming was in full swing.

It was not meant to be live music but audio over the sound system as

everyone understood it to be that, but it is to be expected that there

is a consistent correlation between what is visible on stage and what is

produced as audio over the sound system.

Drumming

This lapse in Daasa’s drumming, was when Champika began her ‘drunken

dance’ to satiate Daasa’s lust for some sensual entertainment to the

‘beat of his drum’.

The symbolism that could be interpreted from it is that Daasa was so

intensely in rapture that the ‘music in his head’ was what was

represented to the audience via the sound system and the actor on stage

was actually supposed to show how the character was not conscious of the

fact that the music had stopped but the dance was going on. The symbolism that could be interpreted from it is that Daasa was so

intensely in rapture that the ‘music in his head’ was what was

represented to the audience via the sound system and the actor on stage

was actually supposed to show how the character was not conscious of the

fact that the music had stopped but the dance was going on.

Critical appraisal of a performance must be read in the context of

the genre attributes it overtly establishes to the viewer. However, this

is not to say that the play did not have its share of symbolism.

Symbolic elements in terms of diction, such as when Daasa says to ‘dance

to the beat of his drum’ and certain elements of stagecraft such as

lighting, presenting symbolic significations that the viewer could

‘read’ in terms of the theatre’s visual narrative methods, as how time

changes from night to daybreak, or the merriness of a moment of song

driven by drink, could be highlighted by colourful lighting that

represents the ‘mood of the moment’ were present in the performance.

Daasa, the incorrigible

What was represented by the central character –the ‘master of the

manor’ –Daasa, was rather shocking for the scathing brutishness he

demonstrates.

The belting of Lechchami as though she were a convicted criminal

being ‘judicially punished’ or vermin that must be exterminated was a

scene that created a shock that created an ‘audible silence’ among the

viewers. But then Daasa was not completely bare of attributes that made

him ‘worthy’.

He appears to be a man set on showing that he is crude but ‘just’

man, albeit on his own terms.

He doesn’t want anyone to think that he didn’t treat his woman right,

the treatment in this case being the provision of some bare necessities

as three meals a day and clothing.

It is purely the most rudimentary economic aspect of a domestic

relationship where the most primordial interplay of duties and

obligations between a man and his woman define a valid union in

domesticity.

The questions of ownership as to who has the right to demarcate a

household as belonging to one or the other and under what circumstances,

is a line of argument that came out strongly in the story.

When Daasa brings his woman to his abode, the ‘Villa de Daasa’, he

lays down the ground rules in a longwinded monologue. It is meant to

serve as a verbally formed binding contract should the woman indicates

her willingness to stay.

There lies the first instance of showing his sense of honour. There

is no ambiguity in what he offers. He is a man true to the word he

offers at the outset. Perhaps there is in that attribute, a worthiness

in Daasa as not being ‘forked tongued’.

Unpretentious

He makes it abundantly clear to everyone that he disdains

pretentiousness. He evokes laughter from the audience when he gets

flummoxed as to how his dictates fail to get due recognition. He gets

astounded as to how he is ‘losing ground’ in his role as self-proclaimed

lord and master.

The audience cannot help but love him in such moments. He is threaded

with buffoonery in the right doses at the right time to avoid being a

fulltime villain and criminalised beyond redemption.

In that perhaps we see the ‘craftiness’ of the directorial craft to

mould the actor’s characterisation to compel an average viewer to be

conferred a dichotomy as to how to judge Daasa.

Lechchami

Is he the kind of man you would love to hate or would hate to

dislike? The answer may not be clear cut. But wife beaters of the most

gruesome degree are very much a reality. That is the afterthought the

play offers in respect of the domestic violence theme.

Lechchami, commendably played by Ravini Anuradha, being a destitute

‘Tamil woman’, created a notable schema of social politics that would

have been otherwise, had she been a Sinhala woman.

It shocked me to see how the disparaging way in which her destitution

was given description by Daasa when speaking with his bosom friend

Saleem Bawa played well by veteran actor Dharmapriya Dias.

To Daasa and Bawa, women brought into their slum and given residence

are chattels that are ‘finds’ off the street like cattle lost after

straying from the herd and up for the grab.

Lechchami is a woman cast out of the house by her husband due to

being a barren woman and thus made destitute. Daasa says he found her

skulking around the Hindu kovil in Wellawatte near the flower vendors. Lechchami is a woman cast out of the house by her husband due to

being a barren woman and thus made destitute. Daasa says he found her

skulking around the Hindu kovil in Wellawatte near the flower vendors.

And he had offered her his standard offer made to six women before

her –food, shelter and clothing, in exchange for functioning as a

domestic servant and satiating his needs as a man.

At one point, Daasa who finds in Lechchami a very docile and

subservient woman, when ordering her about, asks her –‘Sinhala therenne

nadda?’ (Don’t you understand Sinhala?).

I was shocked by that line given the context of the ethnic factors

involved. Although it is very commonly said between people of the

Sinhala community, used jovially and as well as a reprimand, given the

present scale of issues involved in our society one cannot say it is

appropriate to say for a Sinhala person to a Tamil person. It is an

insinuation of the addressee’s level of intelligence to grasp a simple

matter.

Yet to Daasa it was as natural as breaking wind. Either he is

unconscious to the possibility that it would seem disparaging to her on

account of her ethnic identity, or he simply doesn’t give a hoot.

There is no question that the play posits the character of Lechchami

as the person who would win the sympathy of the audience en bloc due to

her station in life and the predicaments faced in the ‘Daasa residence’.

Macho and savage

Daasa’s degree of masculinity in terms of the untameable savageness

within, which he signifies through his conduct in relation to Lechchami,

takes a markedly different turn in relation to Champika who is

compellingly played by Nilmini Buwaneka.

The reason that Daasa puts up with her assertiveness and brashness

which are utterly unfeminine and devoid of any feminine gentleness is on

account of her ‘physique attributes’. It is the aim of the carnal

creature within Daasa that leashes him to her despite her shortfall of

fulfilling the needs of a housekeeper, which is one of the fundamental

conditions bound to the offer of residence, made to any woman.

Champika and her behaviour are an outright assault on the very

concept of masculinity and maleness.

The sexual allure she is capable of generating from the likes of

Daasa and her estranged husband ‘retired police constable Indrapala’

portrayed very well by Hemantha Eriyagama, is her main resource.

Because the finale proves that the ‘tough talk’ she puts on is

incapable of being at least an effective shield let alone a sword when

Daasa’s demonic anger drives a strangling hold on her throat, choking

the life out of her.

‘Power’, in that moment being defined in its most primordial

signification – as unleashing violence upon the body of another, and

thus the determinant as to who can actually claim to be ‘in charge’. |