No quite dead, not quite alive

Painting's obituary has been written several times

over the past 150 years. But it's now experiencing a major revival,

writes BBC's Jason Farago. :

|

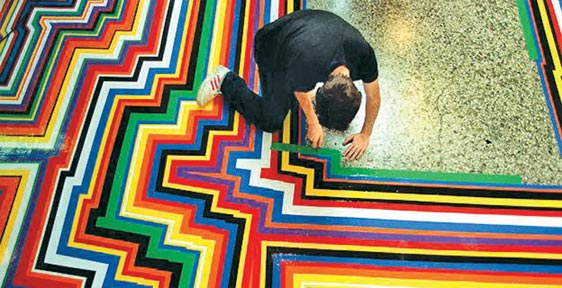

Jim Lambie’s painting installation Zobop (Tom Pilston/The

Independent/REX) |

Something funny has been happening with painting lately - it seems in

terrible shape and yet also in better health than ever. The endless boom

of the art market, which privileges painting and especially abstraction,

has given us a new generation of 'zombie formalists', churning out safe,

easily sellable pictures that look good in digital reproduction and in

the booths of ever-multiplying art fairs.

And yet, beyond the frenzied market scene, the art of painting seems

to be thriving. Biennials that used to contain nothing but video and

installations now bulge with not just abstraction but also figurative

painting - last year's Gwangju Biennale in Korea was a feast of

representational art.

Is painting healthy or sick? And why is it so hard to tell? The

Forever Now, a divisive show of contemporary painting at the Museum of

Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, argues that painting is as healthy as

it's ever been - it just isn't interested in being novel anymore, and

instead recycles or redeploys pre-existing styles for new purposes.

Whether or not that argument convinces you or not (it didn't convince

me), the very fact that MoMA has organised a contemporary painting show

for the first time since 1984 attests that the stakes of painting are

higher than they've been for a while.

Painting Now, a new book by the art historian Suzanne Hudson, takes a

much deeper and more historical look at the status of contemporary

painting than MoMA's The Forever Now. It takes in the work of more than

200 artists, and yet it's much more than the usual coffee-table survey.

Hudson shrewdly looks away from style as she assesses the state of

painting, and instead insists that "a painting [be] tested or evaluated

relative to the history and tradition of the medium".

That gives her the welcome freedom to think not only about paintings

themselves, but about their motives, their production and distribution,

their framing and their institutions.

It also means that, unlike many fans of painting happy to brush away

recent history, Hudson dives headfirst into the choppy waters of

painting's status among the arts.

Twin blows

Painting has been declared dead so many times over the past 150 years

that it can be hard to keep track. But in her introduction, Hudson

pinpoints two developments in the history of art that shook painting to

its foundations, in both cases almost fatally. One was the invention of

photography in the 1830s. Photographs did more than just depict the

world better and faster than painting; they also made entire painterly

languages defunct, from military painting to academic portraiture.

("From today, painting is dead," the academic painter Paul Delaroche is

purported to have said after seeing a daguerreotype for the first time.)

Ever since, painting has in some ways functioned in dialogue with the

camera.

|

Luc Tuymans, The Secretary of State, 2005

(Alamy/Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London) |

In some cases that dialogue takes the form of rejecting photographic

realism, such as in the unnatural colour of Van Gogh. Or the dialogue is

between equal partners. That can be via the use of silkscreened imagery,

most famously by Andy Warhol; via a hyperrealism of Richard Estes or

Franz Gertsch, whose paintings are 'more photographic' than photographs;

or via more painterly effects that nevertheless advertise their

photographic source, as in the art of Gerhard Richter and Chuck Close.

After photography, the other body blow to the primacy of painting

came in the 1910s, when Marcel Duchamp elevated a bicycle wheel, a

bottle rack and an upturned urinal to the status of art.

Even more than photography, the ready-made object struck at the heart

of painting's self-justification. Not only did Duchamp recalibrate the

terms of artistic success, privileging ideas over visuals. He also

eliminated the need for the artist's hand in a way photography never

entirely did. (Indeed, many photographers of the early 20th Century,

from Ansel Adams to Edward Steichen, consciously imitated painting

techniques.) Duchamp's insurrection removed technical skill as a

painterly virtue, and by the 1960s an artist like the minimalist

sculptor Donald Judd could confidently say, "It seems painting is

finished."

Some styles of painting really did undergo a kind of death in the

20th Century. So-called neo-expressionism, whose big bad canvases by

such figures as Julian Schnabel and Francesco Clemente fetched millions

in the 1980s, may have pleased the market but had little to offer anyone

who cared about the history and potential of the medium. Today's 'zombie

formalism' is much the same. But painting that acknowledges the

challenges the medium has faced and builds from there is doing very well

indeed. "Painting, too, is capable of manifesting its own signs," Hudson

writes. "Painting has become more, rather than less, viable after

conceptual art, as an option for giving idea form and hence for

differentiating it from other possibilities."

Premature burial

In the last century abstraction was seen as the supreme, even the

only, form of advanced painting. But in recent decades, as painting has

thrown off the yoke of avant-garde prescriptivism, figurative painting

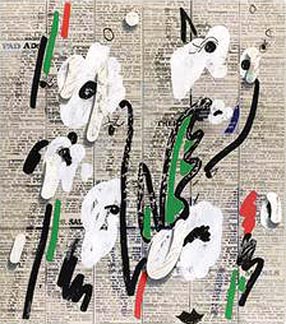

has been on a noted upswing. Some make use of appropriated media

imagery, notably Luc Tuymans, whose colour-sapped paintings of

Condoleezza Rice or Patrice Lumumba redeploy photographic

representations. (Last month, he lost a plagiarism suit against the

photographer of one of the images he painted; he is appealing.) Others

prefer observation without cameras, such as Josephine Halvorson, who

paints modest tableaux of rural buildings from arm's length, or Liu

Xiaodong, whose plein-air paintings of young Chinese students recall

Manet and Courbet. Perhaps the biggest omission from Hudson's book is

Catherine Murphy, who is not only one of America's greatest painters but

also a professor who taught generations of students at Yale Art School.

|

Laura Owens, Untitled, 2013 (The Museum of Modern Art, NY.

Enid A Haupt Fund. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar) |

Painting has also moved off the canvas, and even off the walls. Imran

Qureishi, from Pakistan, makes not only miniature paintings but also

all-encompassing installations drawn directly on the floor and the

walls, often featuring blooming floral motifs in blood-red acrylic. Jim

Lambie plays off the architecture of the spaces in which he exhibits,

covering the floors with multi-coloured vinyl tape. Paintings also now

function frequently not as stand-alone artworks, but as elements of a

larger network of artistic procedures.

The influential painter Jutta Koether, for instance, does not only

paint; she also designs the presentation of her paintings, complete with

special lighting and ad hoc viewing platforms, and sometimes performs in

the gallery alongside them.

Koether's expansive practice of painting is a good counterweight to

the big question surrounding the rude health of the medium - a question

that goes unasked in Hudson's fine book. That is the question of the

market. When I visited her studio a few years ago, the artist RH

Quaytman - known for her brainy, reflexive paintings organised into

chapters, like a book - lamented how the demands of collectors and

markets were powerful enough to move art history. "Art fairs, jpegs and

the entire bloated art market are responsible for the resurgence of

painting as opposed to all other art forms," she told me.

"I'm sad that it is the structure of the art market that has

revalidated and reinvigorated painting.... It's easy to store, it's easy

to transport, it works well enough on the internet: it turned out that

painting was, despite itself, the perfect tool. The problem is, whose

tool is it?" Every painter should ask themself that question when they

turns to the empty canvas.

(This article was originally published in BBC Culture)

|