The greatest feasts in Art

by Jason Farago

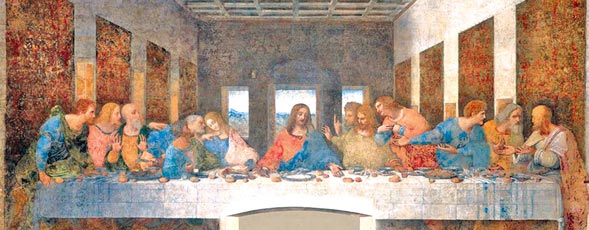

Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper, late 1490s

Depictions

of Jesus' final meal with his 12 apostles in Jerusalem have been a

popular artistic subject since the days of early Christianity, but

Leonardo's is the most famous -despite severe damage and clumsy

restorations that have left it a shade of its former self. Christ,

sitting dead centre at the composition's vanishing point, proclaims that

one of his apostles will betray him; Judas, fourth from the left, leans

back and reaches incriminatingly for a piece of bread. There's no

paschal lamb to be seen on the apostles' feast, but rather grilled eel

and orange slices, off to the right. (Leonardo da Vinci) Depictions

of Jesus' final meal with his 12 apostles in Jerusalem have been a

popular artistic subject since the days of early Christianity, but

Leonardo's is the most famous -despite severe damage and clumsy

restorations that have left it a shade of its former self. Christ,

sitting dead centre at the composition's vanishing point, proclaims that

one of his apostles will betray him; Judas, fourth from the left, leans

back and reaches incriminatingly for a piece of bread. There's no

paschal lamb to be seen on the apostles' feast, but rather grilled eel

and orange slices, off to the right. (Leonardo da Vinci)

Paolo

Veronese, The Wedding at Cana, 1563 Paolo

Veronese, The Wedding at Cana, 1563

This massive feast scene has the singular misfortune of hanging

across from the Mona Lisa in the Louvre's Italian wing, thus making it

one of the most ignored masterpieces of all of Western art. The

mega-wedding, at which Christ has just turned water into wine, has been

transposed from Cana to contemporary Venice. The finely dressed guests

seem to be on the dessert course, but note that none of them is actually

eating. While a genre scene might depict lower-class wedding-goers

consuming food and drink, here the feast is a public pageant, a showcase

for wealth and power. (Paolo Veronese)

Diego Velázquez, Triumph of Bacchus, 1628

Nicknamed

'Los Borrachos' -the drunks -this important early work by Velázquez

features the god of wine, pale-skinned and crowned with ivy, alongside

leathery-faced workers who are wearing much more sober and Spanish brown

cloaks. It's one of his few mythological scenes, and it departs from

earlier depictions of Bacchic revelry, which usually featured prancing

nymphs and rolling hillsides. Velázquez's move to a more naturalistic

style, more common to the genre scenes known as bodegones, suggests he

sympathised with the desire of these men to let loose after the day was

done. (Velázquez) Nicknamed

'Los Borrachos' -the drunks -this important early work by Velázquez

features the god of wine, pale-skinned and crowned with ivy, alongside

leathery-faced workers who are wearing much more sober and Spanish brown

cloaks. It's one of his few mythological scenes, and it departs from

earlier depictions of Bacchic revelry, which usually featured prancing

nymphs and rolling hillsides. Velázquez's move to a more naturalistic

style, more common to the genre scenes known as bodegones, suggests he

sympathised with the desire of these men to let loose after the day was

done. (Velázquez)

Peter

Paul Rubens, The Feast of Herod, 1635-38 Peter

Paul Rubens, The Feast of Herod, 1635-38

The ultimate party foul: you lift up the lid on the serving tray, and

there, staring back at you, is the head of John the Baptist. Rubens's

grand painting, stylish and macabre by turns, shows the moment when

Salome, having danced for her stepfather Herod, wins her prize of the

decapitated saint - which is presented as just another course at this

feast, along with lobster and game birds. Herodias, Salome's mother,

pokes at John's tongue with a fork, while her husband's eyes bulge in

horror. (Peter Paul Rubens)

John Martin, Belshazzar's Feast, c 1821

Martin

was one of the strangest painters of 19th-Century England, given to

apocalyptic visions that often tipped into kitsch. Here he depicts a

dizzying scene from the Book of Daniel, in which the titular king of

Babylon gets the bad news, glowing on the wall at left, that "thou art

weighed in the balance and found wanting." The feast in the foreground

is overshadowed by Martin's comically grand fantasy of Babylonian

architecture, with columns extending out to infinity, and the terrible,

lightning-cracked sky above. (John Martin) Martin

was one of the strangest painters of 19th-Century England, given to

apocalyptic visions that often tipped into kitsch. Here he depicts a

dizzying scene from the Book of Daniel, in which the titular king of

Babylon gets the bad news, glowing on the wall at left, that "thou art

weighed in the balance and found wanting." The feast in the foreground

is overshadowed by Martin's comically grand fantasy of Babylonian

architecture, with columns extending out to infinity, and the terrible,

lightning-cracked sky above. (John Martin)

Jan

Steen, The Dissolute Household, 1663-4 Jan

Steen, The Dissolute Household, 1663-4

While feast scenes in the High Renaissance depicted gods or nobles,

Dutch artists in the 17th Century turned to domestic scenes, sometimes

with a moralising gaze. Steen's revellers indulge in just about every

sin imaginable: the man in black is trying to seduce the serving maid,

while the woman in the foreground is so busy getting her drink on that

she doesn't notice she's trampling a bible underfoot. As for the large

ham that served as the centre of this feast, it's been abandoned on the

floor, ready to be eaten by the family cat. (Jan Steen)

James Ensor, The Banquet of the Starved, 1915

After

the German army occupied Belgium at the start of World War One, Ensor

painted this bitter parody of the Last Supper. Instead of a sumptuous

paschal feast, the diners are sitting down to a table with just two raw

carrots, an onion, and insects, in evocation of the horrible famine that

overtook Belgium in the year Ensor completed the work. The diners are

grabbing each other in poses that could be sexual or violent or both,

while in the background hang three paintings-in-the-painting: tableaux

of skeletons, dancing or fighting. (James Ensor) After

the German army occupied Belgium at the start of World War One, Ensor

painted this bitter parody of the Last Supper. Instead of a sumptuous

paschal feast, the diners are sitting down to a table with just two raw

carrots, an onion, and insects, in evocation of the horrible famine that

overtook Belgium in the year Ensor completed the work. The diners are

grabbing each other in poses that could be sexual or violent or both,

while in the background hang three paintings-in-the-painting: tableaux

of skeletons, dancing or fighting. (James Ensor)

Giovanni

Bellini, The Feast of the Gods, 1514 Giovanni

Bellini, The Feast of the Gods, 1514

The divine banquet was a frequent theme of Italian painting in the

16th Century, and in fact many Renaissance artists would stage their own

banquets with Olympian costumes and lavish eats. (The painter Andrea del

Sarto once designed a church made of sausages and parmesan.) Bellini's

final major work - made with assistance from a young Titian, his student

- is a masterpiece of this mythological genre: the fertility god Priapus

is putting the moves on a nymph on right, while Jupiter and the other

divinities are drinking wine. An innovation: Chinese blue-and-white

porcelain, newly imported to Europe. (Giovanni Bellini)

Édouard Manet, Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe, 1862

The

greatest painting in the history of Western art, rejected by the Paris

Salon and scorned by Napoleon III himself, broke all the rules of

perspective, illusionism, and iconography (why are the men in modern

dress, why is the woman naked, why aren't they looking at one another?).

But Manet's up-to-the-minute pastoral scene is not much of a picnic:

just some fruit and a brioche, tumbling out of a basket and onto the

grass and the nude woman's discarded clothes. What's significant is not

the fanciness of the picnic, but its newness - no more mythology, no

more moralising, just the blunt facts of modern life. (Edouard Manet) The

greatest painting in the history of Western art, rejected by the Paris

Salon and scorned by Napoleon III himself, broke all the rules of

perspective, illusionism, and iconography (why are the men in modern

dress, why is the woman naked, why aren't they looking at one another?).

But Manet's up-to-the-minute pastoral scene is not much of a picnic:

just some fruit and a brioche, tumbling out of a basket and onto the

grass and the nude woman's discarded clothes. What's significant is not

the fanciness of the picnic, but its newness - no more mythology, no

more moralising, just the blunt facts of modern life. (Edouard Manet)

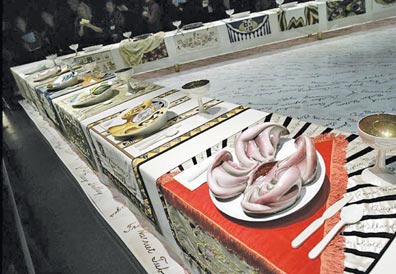

Judy

Chicago, The Dinner Party, 1974-79 Judy

Chicago, The Dinner Party, 1974-79

The iconic work of American feminist art is the ultimate feast: a

banquet table set for more than three dozen great women, from Sappho and

Hatshepsut to Emily Dickinson and Virginia Woolf. The focus isn't the

food but the covers: each guest has a unique place setting, most of

which feature plates in the form of a certain part of a woman's anatomy.

Chicago completed the work with the help of 400 volunteers, and while

most feasts put the guest of honour in the centre, this one is in the

shape of an equilateral triangle, with uniform billing for everyone.

(Stan Honda/AFP/Getty Images)

-BBC Culture

|