|

Photo: John Russo |

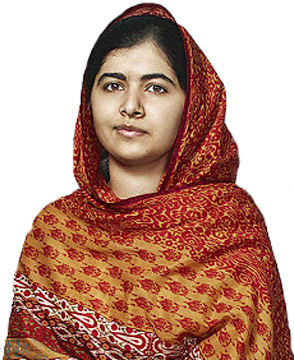

Pizza-loving, double jointed and scared of her

teachers:

Meet the real Malala

by Louise Carpenter

Malala Yousafzai sits very still, a rainbow of colour in the corner

of a vast, drab, empty room. Security personnel with earpieces and

walkie-talkie equipment mill around downstairs; watching, patrolling.

They spill out on to the street around us, a secret location on the

outskirts of west London.

It’s a reminder, as if one were needed, that Malala – shot in the

head on October 9, 2012, aged 15, on her way home from school in the

Swat Valley, Pakistan, for speaking out against the Taliban and its ban

on female education – is still under threat. She is guarded, at least

for public events like today, the launch of a new documentary film about

her life: ‘He Named Me Malala’. Her mother, Toor Pekai, a beautiful

woman with green eyes, prays for her every day, Malala tells me. “Please

God, keep Malala safe today,” Pekai said this morning back in

Birmingham, where the family have lived since Malala was shot. It’s a

prayer just like those Malala used to say to protect her father,

Ziauddin, back in Pakistan when he was the main campaigner in the

family.

Once, they found a letter from the Taliban taped to the gate of the

Khushal Girls High School, which he ran and Malala attended. “Sir,” it

said, “the school you are running is Western and infidel. You teach

girls and you have a uniform that is un-Islamic. ‘Stop this or you will

be in trouble and your children will weep and cry for you.” Ziauddin

responded the next day in a letter to a newspaper: “Please don’t harm my

schoolchildren because the God you believe in is the same God they pray

to every day. You can take my life but please don’t kill my

schoolchildren.”

Malala began speaking out about herself back in 2009 when she was

just 12, first writing a blog for BBC Urdu under the name ‘Gul Makai’,

and then finally stepping up, unbidden, to the microphone with face

uncovered. “It is my own passion, my own choice that I said I will

speak,” she says now of the subsequent accusations that her father made

her a figurehead for his own message.

I am Malala

It is what led her to be singled out among her classmates – all of

them clever girls committed to the cause – by the masked gunman. “Who is

Malala?” the Taliban fighter asked. Then he shot her. Everything she has

done since has been in defiance of the attempt to silence her. Her book,

‘I am Malala: the Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the

Taliban’ (2013), and its sister book for children, ‘Malala: the Girl who

Stood up For Education and Changed the World’ (2014), are responses to

that deadly question: Who is Malala? The Malala Fund, set up two years

ago, campaigns for girls’ secondary education throughout the world. Last

year, Malala was the youngest recipient ever of the Nobel Peace Prize.

|

Malala in hospital in late October 2012, with her mother,

father and brothers by

her bedside |

Malala is here with her father, although I am to meet her alone. They

are always together at her international speaking engagements, meetings

(at the UN, White House) and trips (Syria, Nigeria, the US) – and so it

is at the international launch of ‘He Named Me Malala’. The film,

directed by Davis Guggenheim, is a mixture of animation, old and new

footage and voiceover; a subtle retelling of her life and attempted

assassination that can – and should – be watched by children of 10

upwards. It’s hard not to feel star-struck in the days leading up to

meeting Malala. The security hoopla, to which she has become accustomed

while meeting some of the most influential world leaders, only adds to a

low-level stomach churning. What will she be like, this child/woman

Nobel Laureate?

Mala’s inspiration

Malala is dressed in a salwar kameez of deep purple, with pink

trimmings, her head covered with a purple scarf. Her hair is twisted

over her shoulder in a low ponytail. She’s wearing high pastel-pink

wedge sandals and her toenails are painted to match.

Her handbag, adorned with embroidered flowers, lies, by her feet. She

smells gorgeous – she giggles when I compliment her – and says it is a

scent chosen by her mother. “I do like nice clothes,” she says (although

she’s not a ‘girly girl’ and her favourite colour has changed from pink

to purple). “And my mother really takes care of me. She wants me to look

good, and I don’t get the time to buy things myself.”

Malala’s intense relationship with her father is well known. He

inspired her from infancy. As he says in the film, “We came to depend on

each other, like one soul in two different bodies… It was attachment

from the very first moment I saw her.” She remembers him telling her, “I

will protect your freedom, Malala. Carry on with your dreams.” “Don’t

ask me what I did,” he says in the film. “Ask me what I didn’t do. I

didn’t clip her wings.” He added her name to the family tree; the first

female to be included for 300 years. She worried about him constantly in

Pakistan: that he would be targeted by the Taliban for his outspoken

opinions, dragged away from the school he started, or their home, and

killed.

Where’s my father

She checked the gates and windows of their home every night. Her

mother kept a ladder against the side of the house so he could escape if

he needed to. After Malala was shot, and had lifesaving surgery on her

brain, the first question she asked after waking up in hospital in

Britain was, “Where’s my father?” Pekai does not feature nearly as much

in the film, but Malala is especially keen to talk about her, “It is

really hard for a woman [from Pakistan] to think totally in a different

way, but she did it… and now she has this passion [to learn],” she tells

me.

|

Meeting Barack Obama at the White House in 2013

Photo: GETTY |

In the film, Malala says of her mother, “I think she is not

independent or free because she is not educated.” But Malala turned 18

this year and seems to have a growing emotional maturity, combined with

an understanding of her mother’s different strengths: her morality, her

strong faith, her thirst to educate herself (she left school at five and

was illiterate), which she does now every day at college.

All these things have deepened Malala’s respect for her mother, who

is uncomfortable in the limelight, living as she has for much of her

life in purdah. “She truly believes in telling the truth and standing

against what is wrong,” says Malala. “My mother is learning too –

through the passage of time – that covering your face and what kinds of

clothes you wear are not issues, although she is proud of our culture.

She had felt it was part of her religion, and part of what was right,

but now she sees that as being truthful and honest and just.” It is

something that struck Laurie MacDonald, one of the film’s producers.

“Toor Pekai is someone who observes cultural traditions and has a

tremendous, yet quiet strength, which I think has a lot to do with who

Malala has become.”

My mother

“I don’t know how to explain her personality because it’s very

complex,” says Malala. “She has this strong belief in her heart of

Islam, but she does not really give powerful speeches like my father. I

might be [more like her] in that respect because my father is quite open

and he says whatever is in his heart, which is how my grandfather was.

“I do speak, but I don’t speak like my father or my grandfather. I am

usually very quiet and my speeches are well controlled. I don’t get

emotional – and my mother is the same.”, “The terrorists thought they

would change my aims and stop my ambitions, but nothing changed in my

life except this: weakness, fear and hopelessness died. Strength, power

and courage were born.” “Toor Pekai is more than present in the family

home,” says Malala’s literary agent, Karolina Sutton, “but she herself

chooses how present (or not) she wants to be in the media.”

“My mother,” Malala says, “has inspired both of us, not just me but

my father as well. She is like the person behind both of us. We need to

stay happy, we need to stay positive and saying jokes. I used to cry

when I was little, ‘Why is my mother so beautiful and I am not?’ She is

a great person, and she has not just a face of beauty but beauty of

heart.” It is hard to over emphasise Malala’s sweetness and

self-effacement. She has just moved into the sixth form after getting 10

GCSEs, all A*s and As. “I should be worried about my grades,” she says

(we meet before she got the results).

|

Malala with her mother, Toor Pekai

Photo: GETTY |

She is two years older than her classmates, having joined a younger

class for obvious reasons, and is now taking A Levels in history,

economics, maths and religious studies. The plan, she says, is to read

PPE at Oxford (although her father said recently that she is considering

Stanford University in California). “I’m not going to write any award on

my [application] CV. I’m just going to write down my work experience and

my schoolwork.”

This year she did two work-experience placements with a school friend

from Edgbaston High School in Birmingham, both working for social

change. She made coffee, “and wrote questions, arranged projects – and I

just really felt like a normal person”. She loved it.

Normal person

Did being a normal person feel good? “Very good,” she says, “very

good”. “I do sometimes go to the cinema,” she adds. “And to markets, and

people do come [up] and sometimes people hug me and say, ‘Can I take a

picture of you?’ and some people just say, ‘We support you.’” But there

is an element of her, too, that needs to disengage from her public

persona, particularly when it comes to her own peer group. In class, she

says she never speaks up, which must pose an interesting dilemma for her

teachers, given her meetings with Barack Obama and Ban Ki-moon and her

accomplished political speeches on the world stage.

“Outside the school, I am this girl who is speaking to the world

leaders but inside school, I stay quiet and I am very obedient. I really

believe that whatever the teacher says, it is always right. I am really

fond of them – and I am a bit scared as well.

“But they are very nice and supportive of me.” Sometimes, she says,

they do grade her work a B and write, “Malala needs to focus more on

this topic.” If Malala has any nagging worries, they are not about the

Taliban but the prospect of getting a C at school. “I do worry about my

grades! I mustn’t get a C.” Life in England has not always been easy for

her. In the beginning, post-rehabilitation (her injuries were extensive:

to this day, she still needs to massage the right side of her face, a

result of a severed nerve from the bullet), she found it hard to settle

at school. Everything was new and foreign. Apart from a slight facial

lopsidedness, barely noticeable – “I notice it because I see it in the

mirror every day” – she looked the same as her classmates; same

dark-green uniform save for a longer-length skirt and headscarf, and yet

in those early days, she had a completely different frame of reference,

not only because she had come overnight from the Swat Valley but, in

particular, because she was used to an entirely different education

system, weighting marks in a different way. (“I found that very hard –

in Pakistan you got marks for handwriting and just writing a long

answer.”)

I am the same Malala

But slowly the homesickness has eased (“When I am in a car looking

through the window I sometimes think I am [here] in England but it’s

just for a short time,” she says poignantly), and the prevailing spirit

is her optimism. “I am the same Malala. I have been given a new life and

this life is a sacred life.” She still phones her best friend, Moniba,

in Pakistan to ask, “What’s the breaking news? The gossip. Moniba

informs me about everything so I can feel updated,” Malala explains to

me.

Malala

Yousafzai: her story so far

July 12, 1997

A future activist is born

Malala Yousafzai is born in Mingora,

Pakistan. Her mother is Tor Pekai Yousafzai and her father

is Ziauddin Yousafzai - a well-known social activist.

2007-2008 (10-11 years old)

The Taliban arrive in Swat

Groups of Taliban begin to appear in

Pakistan’s Swat valley where Malala and her family live.

They warn local people against music, dancing and DVDs

before issuing an ultimatum at the end of 2008 for all

female education to cease.

2009 (11 years old)

Malala writes for the BBC

Malala writes an anonymous blog on the BBC

website called ‘Diary of a Pakistani Schoolgirl’. It charts

her fear of being prevented from going to school. Shortly

afterwards she appears on Pakistani and American TV

demanding her right to an education.

October 9, 2012 (15 years old)

Taliban militants shoot Malala

As she returns from school Taliban

militants board her school bus, single out Malala and shoot

her in the head.

2012 (15 years old)

Her recovery begins

Emergency surgery in Pakistan saves

Malala’s life. Her specialist care and rehabilitation

continues at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham,

where she ultimately settles.

March 2013 (15 years old)

Starts school in the UK

Malala begins classes at the independent

Edgbaston High School for Girls in Birmingham. Her

£10,000-a-year fees are funded by the Pakistani government.

July 12, 2013 (16 years old)

Addresses the UN

On her 16th birthday, Malala gets a

standing ovation when she addresses the United Nations. “I

am here to speak up for the right of education of every

child,” she says.

October 2014 (17 years old)

Wins the Nobel Peace Prize

Malala Yousafzai wins the Nobel Peace

Prize for her “struggle against the suppression of children

and young people and for the right of all children to

education”. She is the youngest ever winner of the prize.

July 12, 2015

Malala turns 18

On her 18th birthday, Yousafzai opened a

school in the Bekaa Valley, Lebanon, near the Syrian border,

for refugees. The school, funded by the not-for- profit

Malala Fund, offers education and training to young girls.

Yousafsai called on world leaders to invest in “books, not

bullets.” |

This is the ‘normal’ teenage Malala, the one who inwardly cheers on a

Friday lunchtime because she can eat French fries in the school canteen

instead of the English ‘boiled things’ that she doesn’t like (her mother

cooks only Pakistani food at home), who listens to Katy Perry and

watches Inside Out. The girl who gets irritated by her younger brothers,

Khushal, 15, and Atal, 11, and can’t understand the way they play on

their Xbox all the time. “And Minecraft? I don’t know why they play but

they are crazy for it. They are like typical boys!”

She has one close English school friend now, who must remain

nameless. The girl is not a Muslim and she often helps Malala understand

colloquialisms. “My friend helps me every day, telling me words I

shouldn’t say because I don’t know their other meanings! And she helps

me understand the words in songs.”

The two friends were on their work placements together and visit each

other’s houses. “She comes to our house and we have halal food and we

don’t have wine and she’s fine with it. And then when I go to her home,

they have a very different culture.

“They don’t wear shalwar kameez, they do have wine in the house but I

don’t mind. It’s co-existence, it’s harmony and we really enjoy it. I’ve

never ever thought that being culturally different makes it difficult

for us to become friends. These things make friendship more special

rather than stopping it.”

Pride of Britain

She barely mentions her political career to her classmates, but

sometimes they see her picture in the paper. The one that caused the

most fuss was when she accepted a Pride of Britain award from David

Beckham. “I had no clear idea how famous he was,” she says, giggling.

“And how women and girls really liked him.”

He was probably more smitten meeting you, I tell her. (Some time

after I talk to her, she meets Beckham again in New York and he posts

the selfie, above, with her on Instagram, saying how privileged he

feels.)

In fact, the subject of boys, full stop, sets her off in a fit of

giggles (she seems to quite like Shane Warne and Roger Federer). When I

ask her about how she might protect any future romantic life, say if she

is at Oxford or any university, she laughs again.

“When I talk about going to university, my parents say they will also

go with me! And they are joking and teasing me [saying], ‘We will go

just to keep an eye on you!’ And I say, ‘No! It’s compulsory at

university that parents can’t come!’” Some of the girls she was at

school with back in Pakistan have already disappeared from the

classroom, swallowed up by a life of traditional married subservience.

Two of her friends who were on the school bus when she was shot are

studying at the prestigious international Atlantic College in Wales (Malala

recommended them after she was offered a place but decided to stay in

Birmingham with her family).

When schoolwork allows, they come for sleepovers in Birmingham, where

they might all watch something funny on her iPad (pink case), and she

will impress them with her card tricks or click her double joints and

try to make them laugh with her jokes. “I do like jokes,” she says. “And

when my friends visit, we talk about our old times at school and the

silly things we have done, making fun of others or someone making fun of

us or talking about our teachers… memorable parts of life from the old

days. “I am hopeful I can go back after finishing my education,” she

says of her homeland. “I think only about the future. I don’t really

think about the dangers or the threats. They are gone now.”

The Malala Fund

Since Malala and her father set up the Malala Fund, it has donated

$3.5 million (£2.2m) to local services and global projects working to

educate girls in Pakistan, Nigeria, Kenya, Sierra Leone and countries

housing Syrian refugees. This year, the fund has given further grants to

localised leaders working towards change in their own countries. It is

this campaigning that has taken Malala all over the world, and has

attracted criticism from those against her message; that she is a

mouthpiece for her father’s beliefs: that she is a puppet for the West.

This is where I suspect her mother’s faith and moral strength gives her

ballast.

“Criticism and opposition are always there when you stand up for

something big and when you want to bring change,” Malala says. “I

usually learn from it. Sometimes they say the right thing and sometimes

they say something that doesn’t make sense at all. So I think I have to

carry on my journey. I have to carry on this fight.”

In ‘He Named Me Malala’, she goes to a Syrian refugee camp, where she

looks stricken. “I did cry,” she says, “when I saw these people, with no

hope for home, no hope for children’s safety, no hope for their own

safety, children with no shoes and no food.

“It was horrible to imagine. What have they done? Why should this

person become a refugee? That did make me cry. I don’t usually cry, but

that made me cry.” (It’s an interesting detail, this ability to keep her

emotions in check. Maybe she sees tears as wasted energy, a sign of

hopelessness rather than hope.) “I want to continue my campaigning for

the fund,” she says, “and I’m really proud to have such a strong team.

When I was young, I was interested in becoming a doctor, but then I

thought becoming a prime minister is very important. But now I can’t

promise and I can’t clarify. I am not sure. My fund work will continue,

my work for education will continue, but in terms of a job, I don’t

know.”

He named me Malala

In a way, the small details of Malala’s life are as gripping as the

bigger picture: the way she prefers cupcakes to sweets; that she loves

pizza; that when she was younger, she spent too much time fiddling with

her hair; how she tried to lighten her skin with honey, rosewater and

buffalo milk, so she could be paler-skinned, like her mother. How she

thinks Bella from Twilight is fickle and Edward is too boring because

she and Moniba and her other friends in Pakistan think that ‘he doesn’t

give her any lift’.

Why are these insights into Malala’s life so wonderful? It is

because, I think, they show her to be human rather than superhuman;

because they allow her to be considered normal even when we know that,

ultimately, Malala Yousafzai is very special.

He Named Me Malala will be released on November 6

(This article was originally published in Telegraph

UK) |