Seeking the place my father once called home

by Dakshana Bascaramurty

|

Theivam PathyĒ: My dadís childhood home in Atchuvely. |

My father never read to me when I was a kid, but could sometimes be

persuaded to tell a bedtime story from memory, drawn from a stock of Sri

Lanka-ified versions of Aesop's Fables.

In the original parable of the crow and the fox, the fox flatters the

crow, who is holding a piece of cheese in his beak, into singing for

him. This prompts the crow to drop the cheese, and the fox catches it.

My dad's version was pretty close to Aesop's original, except that the

hunk of cheese was actually a vadai.

A crow eating vadai. To a five-year-old growing up in suburban north

Toronto, this was an absurd image, and one I added to a patchwork of

others in an attempt to understand Sri Lanka, where my parents were from

but rarely spoke to me about. I understood a rough outline of why they

and many other Tamils had left their troubled country and made Canada

their home. I know their history in a meta sense, but few of the

details.

Dad's silence

My dad's life, especially, was a mystery. Although my parents spoke

Tamil in the house, enrolled me in bharatanatyam classes as a child, and

made regular pilgrimages to a Hindu temple near Pittsburgh, the only

tangible evidence of my dad's life in Sri Lanka were a few wallet-sized

black-and-white portraits that had been preserved in yellowed envelopes

or stuck into the crook of a disintegrating photo album.

The younger version of him looked nothing like the man I knew. Who

was this stern-faced stranger whose jaw was narrower, lips were plumper

and hair was more lush than that of my father, 46 and half-bald when I

was born? Was he good at sports, or a klutz like me? What did his

bedroom look like? His neighbourhood? How did he get to school every

day, and did it look more like mine or the one on Little House on the

Prairie?

|

My mother Saro, in Jaffna. |

How far removed from my world was his, on that mango-shaped island

surrounded by the Indian Ocean nearly 14,000 kilometres away?

My dad never responded to my probing questions in a satisfying way.

Like so many of those who even now are heading to Canada in the hope of

a better life, he looked forward rather than behind.

When I was in grade school, there was wistful talk of a possible

family trip there one day, but it never materialised. The enormous

expense was one obstacle, safety a much bigger one. Government forces,

representing the Sinhalese majority, had been at war with the separatist

Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) since before I was born.

By the time the war ended, in 2009, my brother and I were working

adults, living thousands of kilometres away from our parents. Sri Lanka

faded off my list of travel destinations. Maybe I'd never see it, and

maybe that was okay.

In my parent's homeland

Then, this fall, I found myself in my parents' homeland for the first

time - without them.

My husband, Anis, is half Sri Lankan and has family in the country's

south. His cousin Tamarih was getting married this past October, and so

we booked a two-week trip to the country. My long-buried interest in my

so-called homeland was suddenly awakened - not least because the last

leg of our trip would be a three-day sojourn to the North, organised by

Anis's mother. My dad's house became the prime destination of the

journey: In finding it, I hoped to understand him better.

My parents left Jaffna many years before the civil war began in 1983.

In the late eighties, as the hostilities intensified, my grandparents,

aunts and uncles began arriving in Canada, some sponsored by family,

others claiming refugee status.

At one point, before I was born, there were seven members of the clan

squeezed into my parents' two-bedroom apartment in Toronto's High Park

neighbourhood.

Today, according to Statistics Canada, 131,000 Tamils live in Canada;

academic experts put the figure even higher, at close to 200,000. So

many settled in the Toronto suburb of Scarborough - opening up an

extensive network of shops that sell 22-carat-yellow-gold wedding

jewellery or imported spices - that some affectionately call it Little

Jaffna.

Before the war, before the outflow, my dad recently confessed, he had

fantasised about returning to his farming village of Atchuvely. Soon

after he married, he suggested this plan to my mom, and she agreed to

it.

|

Inside the house. |

"When Sri Lanka was in good shape, it was pointless wasting your time

in another country," he recently told me, though, as usual, he held back

on any details about why his homeland was so great. Although years ago

he made one short trip back to Sri Lanka, his plans to settle in

Atchuvely never materialized.

My mother's history

My mother was only slightly more forthcoming than my dad when it came

to her history. One of the few bones she ever threw me was the story of

how her father was almost killed by the Sri Lankan Army a few years

after my parents came to Canada.

Having heard that soldiers were on the way to Urelu, their village,

my grandfather had hid the family down the road. When he sneaked back

later in the day to feed the guard dog, three troopers stormed into the

house. It didn't take long before they found him - hiding, rather

comically, under a pile of burlap sacks.

Two of them pointed guns in his face while another brandished a

knife. He pleaded for mercy, and they let him go - but set the house

ablaze. With the help of neighbours, my grandfather drew water from the

well to put out the flames. Soon after that episode, he and my

grandmother moved to Toronto, living with my parents until they found an

apartment of their own. While downtown Colombo is a 21st-century city,

history seems to have pressed pause on Jaffna. In the 10 days before

arriving there, we'd travelled from the hubbub of Colombo to the tidy

Portuguese-built streets of Galle, from Kandy's steep hills to the tea

plantations of Nuwara Eliya. But the area in and around Jaffna was by

far the most primitive part of the country.

The Sri Lankan Government has spent serious capital on reconstruction

here since 2009, but signs that this was the site of a protracted

conflict were tattooed on the land. We passed the

half-empty shells of bombed houses, some covered with vines that had

twisted around their crumbling facades. It was clear that making Jaffna

whole again will take far more time and money.

Subhas in Urelu

It was only after much prodding that I had finally got my parents to

help co-ordinate a list of places to seek out during my time in the

North. They were pleased with the idea of my going to Sri Lanka, but

didn't exhibit the glee I'd hoped for when I mentioned the journey to

Jaffna.

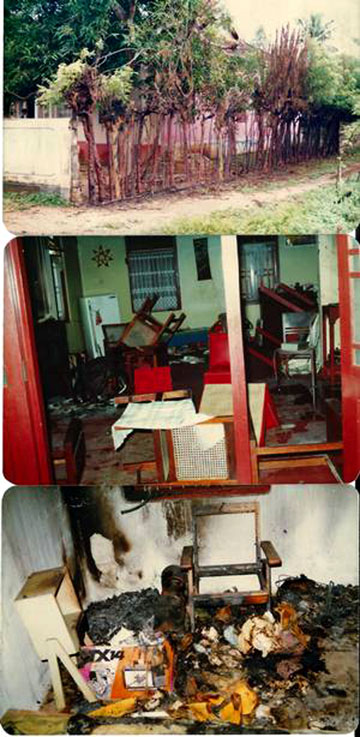

|

My motherís childhood home in Urelu in 1985, after it was

raided by the Sri Lankan army and set ablaze. |

It was my Australian uncle, Yogan Mama - my mother's brother - who

did the heavy lifting, spending hours poking around on Google Satellite

and compiling points of interest in Urelu. Was the village co-op store

still there, he wondered? It was where members bearing ration books

could pick up weekly allotments of sugar, flour, rice, semolina and

Maldive fish.

When the family had dinner guests, my uncle recalled, one of the four

brothers would be sent off into town to Subhas, Jaffna's first ice-cream

parlour. Whoever was dispatched would fill a flask with vanilla, the

only flavour available, and cycle home from the relative hubbub of

Jaffna's town centre to the sleepy village where the family grew

bananas, coconuts, guava and eggplants. The owners of Subhas also ran a

famous hotel of the same name that was shuttered for many years because

of the war.

The hotel has reopened, but the ice-cream parlour, we discovered as

we poked around, is long gone. So were the snack corners where they'd

order rotis and mutton korma for lunch, and the grinding mill where

they'd take coffee, rice and lentils for processing.

In my dad's village, meanwhile, his primary school was still

standing, but the fate of many others, including both of the secondary

schools he attended, was a mystery.

As I set out with Anis and a few members of his family, I had little

optimism we would find what we were looking for here.

Once the second-largest city in Sri Lanka, Jaffna had been hollowed

out by the war, and now has a population smaller than it did half a

century ago. As we drove through this city, with its broken

infrastructure and overhauled population, it seemed like a long shot

that I'd find the place where my dad had grown up, or any traces of my

parents' former lives, for that matter.

The directions my family had offered to my father's childhood home in

the village of Atchuvely were simple: We were to look for a temple built

to honour Pillayar (the elephant god, also known as Ganesh) and, after

finding it, to ask around for the house known as Theivam Pathy.

During the war, a few temples were destroyed; others were occupied by

the army so Hindus couldn't pray at them. Since the end of the conflict,

some houses of worship had been rebuilt, occasionally funded by former

residents who had created lives elsewhere. If we couldn't find the first

landmark, there was little hope. But the Pillayar Temple was there!

An L-shaped structure painted mustard, it reminded me more of a

repurposed farmhouse than the majestic white buildings adorned with

hand-carved deities we'd seen in other parts of the country.

Finally found it

Save for a few smartly uniformed children playing behind the gate at

my dad's old school, there was no sign of a living soul. We'd made the

mistake of showing up during Atchuvely's unofficial nap time.

Just as we were about to throw in the towel, my husband spotted a man

in the distance driving toward the temple on a scooter, and we waved him

over.

"I'm looking for a house called Theivam Pathy. Know it?" I asked in

my rusty Tamil.

"Theivam Pathy," the man said slowly, letting the words marinate on

his tongue for a few seconds.

My dad was born in 1939, the same year The Wizard of Oz was released

in theatres, an odd fact I always held onto because he was so rarely

forthcoming with biographical details.

And so it somehow seemed fitting that, in this journey to learn more

about his life, I had crossed paths with people who brought to mind the

benevolent residents of Munchkinland.

A shirtless, white-haired man in a veshti (a white cotton sarong)

held up with a belt, his cellphone tucked between the layered fabric and

his belly, walked to the gate of a nearby house, eyeing us with what

seemed to be curiosity and suspicion, as if we were Martians. His wife,

a wiry woman with sharp cheekbones, marched up with him, sporting a

faded green cotton dress and a dot of red kungumam on her forehead.

"I'm a visitor from Canada," I began, with a broken Tamil. "My father

used to live here and I'm looking for his house. Do you know Theivam

Pathy?" I asked.

The woman's eyes lit up immediately. "Theivam Pathy? Oh yeah, I know

Theivam Pathy!"

The group at this house now wandered over to the one next door, where

another shirtless man confirmed that Theivam Pathy was just down the

road.

"Just around the corner" means as little in Sri Lanka as it does in

Canada. We rounded many corners, trailing the man in the baseball cap

for what felt like 15 minutes, until he gestured at a house.

|

My father holds me up on my third birthday in 1989. |

|

My mother (far left), with three of her sisters at the

family home in Urelu, a village near Jaffna in the 1960s or

1970s. |

Here it was: a modest bungalow surrounded by a stucco wall painted

the colour of calamine lotion. Two women stood in front of the gate,

chatting.

"Is this Theivam Pathy?" I asked, bracing for rejection.

But one replied: "Yes, yes, this is Theivam Pathy." She turned out to

be the owner.

"This is where Cathiravelu Bascaramurty used to live," I said. "Do

you know of him?"

"Oh, yes, I know that name," she said, nodding.

I turned to my husband, my eyes bulging. This was it.

My dad's home

She offered to let me in for a tour, and I stood there for a few

pregnant seconds, grinning so hard that my cheeks began to ache. This

was all I needed: The house, she told me, had been dramatically

renovated; I'd never seen pictures of its interior or heard my dad tell

stories about the place, so I had no nostalgia, even as a proxy, for it.

My parents had uprooted their lives completely to start anew in

Canada more than three decades ago, and much of the world they'd left

behind had been vigorously shaken up and slowly reassembled in a new

form. But despite all that, there was still a small flicker of my dad's

existence in this tiny, sleepy town.

Behind the house, faded plaid sarongs and batik dresses hung on a

line, shaded by a tree weighed down with dozens of mangoes. I thought I

was scoring when I bought a crate of imported ones for $10 near the

Toronto airport, but here outside my dad's old home they were so

abundant that some would probably rot on the tree before being consumed.

My dad's family never had enough money for bicycles, let alone a car,

so they seldom went to downtown Jaffna.

Their diet was a mix of vegetables and fish with rice - meat was too

expensive, and would probably spoil on the long walk home from town,

anyway. But my dad had grown up with a mango tree in his yard.

A mango tree. This was a good life. And it seemed as if everyone here

were living just as simply and contentedly as he had all those years

ago.

(Dakshana

Bascarmurty is a reporter for Globe and Mail, which initially featured

this article) |