From despotism to democracy

January 8, 2015 and the journey so far:

by Dayapala Thiranagama

That was both the opportunity and the problem. Suddenly, subjects

were told they had become Citizens; an aggregate of subjects held in

place by injustice and intimidation had become a Nation. From this new

thing, this Nation of Citizens, justice, freedom and plenty could not

only be expected but required. (Simon Schama, Citizens, A Chronicles of

the French Revolution, 1989).

|

|

In the Presidential

election in 2010, the common candidate Sarath Fonseka was

defeated electorally and jailed. This was the indelible image

that served as a warning to any future challengers. AFP |

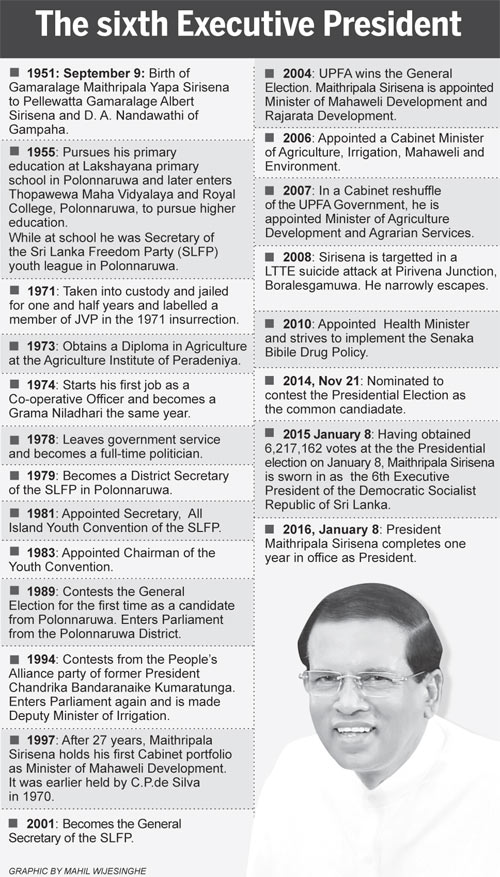

A year ago, a great electoral victory was set in motion with the

coming together of the joint opposition and the common candidate,

President Maithripala Sirisena. This was not the first time a common

candidacy had been attempted in order to challenge the Rajapaksa regime.

In the previous Presidential election in 2010, the common candidate

Sarath Fonseka was defeated electorally and jailed. This was the

indelible image that served as a warning to any future challengers.The

idea of running a common candidate again was therefore fraught with

great personal and political risks. The resounding electoral defeat

handed to Rajapaksa last January seemed a very remote possibility even a

few months prior to the election.

Despite this danger, there were still brave groups of citizens and

individuals who refused to be intimidated. The remarkable political

judgement of the joint opposition, the personal bravery of President

Sirisena and the millions of voters who were ready to call time on the

Rajapaksa regime set the stage for a historic election victory.

A new historical bloc

It was not established political parties, but human rights defenders,

journalists and NGOs who undertook crucial initiatives in opening up and

maintaining Sri Lanka's democratic political space. They defied the

Rajapaksa regime's attempts to shut down political dissent and dominate

all avenues for action, campaigning for liberty and democracy.

In so doing they took considerable personal risks and laid the

crucial foundation for President Sirisena's victory. They were able to

muster an important array of parties and organisations with diverse

ideologies and political philosophies from the UNP to the radical left.

They broke the ice that was hindering the possibility of constructing

an anti-Rajapaksa coalition. This was called 'Platform For Freedom'. In

ideological and political terms this new mustering of forces represented

a watershed in the political discourse of the regime change: they could

not have pioneered that role without dissociating themselves from 'classism'

(Laclau and Mouffe, 1985, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy p, 177), of

the Left political discourse.

The

Sri Lankan Left in pursuing their dream of the working class war against

capitalism had underestimated the crucial nature of the new social

movements. The Left parties had abandoned the struggle against the

violations of personal freedoms, including the right to life, the

oppression of minority communities,the subjugation of women and the

community actions against the destruction of their living environments. The

Sri Lankan Left in pursuing their dream of the working class war against

capitalism had underestimated the crucial nature of the new social

movements. The Left parties had abandoned the struggle against the

violations of personal freedoms, including the right to life, the

oppression of minority communities,the subjugation of women and the

community actions against the destruction of their living environments.

The 'Platform for Freedom' took up some of these issues in their

campaign. Actually the January 8 victory has underpinned the correct

reading of this ground reality. They were not alone in this. The

Movement for Social Justice (MSJ) led by the late Ven. Maduluwave

Sobitha Thera's intervention to campaign for the abolition of the

executive presidency as well as to field a common candidate made a

crucial contribution to the formation of this movement.

Ven. Sobitha Thera's untiring and selfless dedication in persuading

and negotiating with the opposition political parties to field a common

candidate for the Presidential election against Mahinda Rajapaksa

transformed the oppositional forces by contributing hope, passion and a

fighting spirit.

This process then contributed to gaining in Gramscian terms moral,

intellectual and political leadership. It was due to the result of such

work that the opposition started gaining credibility. When Maithripala

Sirisena and others defected from the government ranks and Sirisena

claimed to be the common candidate from the opposition, it was a game

changer.

From this point onwards, political space was opened in a spectacular

fashion. Hitherto excluded people started coming out and openly

expressing their feelings and how they had suffered under the Rajapaksa

family plc. The demand for the abolition of the executive presidency

condensed the democratic demands of the opposition and the cracks

started appearing in a Rajapaksa regime that seemed a few months ago

electorally unassailable.

Common candidacy

President Sirisena's common candidacy was supported by a huge number

of civil society organisations, trade unions and the Left Centre, which

compromised two break away left parties from the government, the Lanka

Samasamaja Party (LSSP) and the Communist Party (CP) after President

Sirisena's common candidacy was announced.

Some of their members remained in the Rajapaksa camp. The Nava Lanka

Samasamaja Party (NSSP) who campaigned vigorously for many years for the

democratic aspirations of the Tamil people also supported the common

candidacy of President Sirisena. The UNP that had the largest voter base

of all the parties in the Sirisena camp actually had made an electoral

sacrifice when they agreed to back the common candidacy of President

Sirisena.

The Tamil National Alliance (TNA) also gave the tactical support to

President Sirisena's common candidacy committing the Tamil voter base

for a political settlement. The Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC) also

supported President Sirisena's candidacy resigning from the Rajapaksa

government.

Thus, President Sirisena was able to garner the support from the

right wing to the Left parties and from the Sinhalese to Tamil and

Muslims to forma new historical bloc called the United National Front

For Good Governance (UNFGG). In its organizational form and political

philosophy,this was an extension of the 'Platform for Freedom'. This

kind of alliance is bound to have ideological and political differences

but they were united behind the common slogan of defeating Mahinda

Rajapaksa.

At the Presidential election Maithripala Sirisena did the unexpected.

His victory over Rajapaksa was a great electoral triumph given the fact

that Rajapaksa used State power, government resources and State media at

will and believed that his victory was securely assured. But those who

often silently suffered under his rule finally had their chance to speak

and vote him out of power.

Significant moment

President Maithripala Sirisena was given the Presidency of the Sri

Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) and it made a significant moment in

legitimising his authority in the Party. The party that was supporting

Mahinda Rajapaksa during the campaign came under his leadership that

offered him the chance of dismantling Rajapaksa ideological and

political influence in the SLFP.

This was a turning point in consolidating the new historical bloc.

President Sirisena's victory ushered in a new air of freedom and

extended much needed political space as never before. The intimidation

and impunity disappeared and the rule of law was gradually restored.

However, apprehending wrong doers from the previous regime has not

happened as quickly as people had wanted. The previous regime left their

criminal apparatus and bureaucracy intact and it was not so easy to make

the law to take its course. Such a situation has helped the wrong doers

of the previous regime.

Despite certain frustrations, the electoral victory of the January 8

was a truly historic one, which also paved the way for the winning of

the parliamentary elections, held in September making it a double

victory for the popular forces. These popular forces none other than

ordinary men and women who belong to all three communities.

For the first time in Sri Lanka's electoral history people whose

democratic rights had been dangerously trampled and their ethnic

existence had been fatally engendered by a powerful political and

military might was overthrown unexpectedly. Those who created such an

organisational framework to unite diverse communities and people who had

multiple and different democratic grievances and issues should be

credited for their novel, historic accomplishment. That also gave a

rational political model for working and wining the democratic demands

outside the class based politics.It is a democratic political discourse

that had been incompatible the broader political practice of the Sri

Lankan Left.

Challenges

The current historical bloc faces four challenges at this current

juncture. Firstly, it faces a stiff resistance from the Sinhala Buddhist

supremacist forces in devolving power to the Tamil community. This

involves a considerable political risk. Even though Rajapaksa lost the

Presidency, the Sinhala Buddhist forces to which he had given hegemonic

expression in the South were reluctant to acknowledge their defeat.

They lost the election but ideological and politically their

electoral base has not shrunk in certain Sinhala Buddhist strongholds.

President Sirisena needs to convince the Sinhala Buddhist constituency

that his approach is safer for the territorial integrity of the country

than Rajapaksa's pseudo patriotism, which suppresses the democratic

aspirations of the Tamil community. Unless President Sirisena is

proactive in pursuing this line it will be harder for him to consolidate

his victory and build on the coalition, which brought him to power.

Secondly, implementation of neo-liberal economic policies would be

politically unpopular. Any move to take measures that would reduce the

existing welfare structures will be deeply unpopular. This is

particularly important in relation to health and education that directly

affect the life chances of the Sri Lankan poor. The protests from the

trade unions and civil society organizations who brought the new regime

to power after the recent presentation of budget proposals demonstrates

the breadth of the protest movements that the government will have to

grapple with.

Thirdly, broad ideological and political differences could destroy

its unity. If ideological and political contradictions are not resolved

in an amicable way within the government, the current bloc will

disintegrate. Diverse and different opinions can be positive if resolved

in a spirit of democracy and tolerance. However, some ministers'

behaviour in public around accusations and counter accusations are

disappointing and show political immaturity.

Fourthly, the government needs to acknowledge that people have a

right to protest. That is how democracy works. It is criminal to attack

or use force against any group of people because they exercise their

democratic right. Unless these challenges are overcome it would be

harder to fully realise the January 8 victory. And this new historical

bloc would not be transformed into a hegemonic project.

Conclusions

The victory of the Presidential election in January 2015 was clearly

a democratic victory of the people in this country and the general

election victory in September by the UNFGG made the democratic

aspirations of the people a realisable prospect.

That is if the Maithripala-Ranil leadership can carry out their

election promises. If they transform the historical block into a

hegemonic project with the inclusion of ethnic minorities with a

devolved power structure, the current coalition would be able to build

'national popular' regime in Gramscian sense.

The Maithri-Ranil leadership needs to persuade the Sinhala Buddhist

constituency to become a political ally in their effort to build a

united democratic country where all communities live with dignity and

respect. If the election promises made by the UNFGG are achieved, that

would make the January 8 victory epochal. Then only can it be called a

democratic revolution. Otherwise it would result in the elite political

classes triumphing and the popular forces would become losers. Then we

will have to start the struggle again.

- Groundviews

|