Are

Women People?

by Mary Chapman

In issues as diverse as domestic violence to media representation,

women have made themselves heard in 2015. So if you read a bitingly

satirical feminist-friendly poem floating around the internet, you'd be

forgiven for thinking it was contemporary: In issues as diverse as domestic violence to media representation,

women have made themselves heard in 2015. So if you read a bitingly

satirical feminist-friendly poem floating around the internet, you'd be

forgiven for thinking it was contemporary:

"Mother, what is a Feminist?" "A Feminist, my daughter, Is any woman

now who cares To think about her own affairs As men don't think she

oughter."

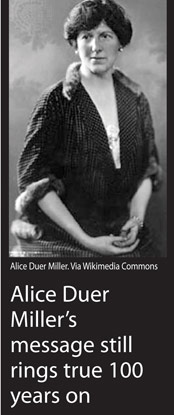

It actually comes from a book celebrating its hundredth birthday: Are

Women People? A Book of Rhymes for Suffrage Times (1915), written by

Alice Duer Miller - the funniest and most influential feminist you've

never heard of.

Are Women People, Mr President?

Are Women People? drew its materials from Miller's popular weekly New

York Tribune column of the same name, which ran from February 1914 until

the New York State suffrage referendum succeeded in November 1917.

The column's title was inspired by the tension between Democratic

President Woodrow Wilson's democratic rhetoric and his insistent refusal

to support woman suffrage.

Miller's

first column framed an excerpt from a campaign speech in which Wilson

had promised to bring the 'Government back to the people' under a bold

headline that posed the question Miller asked repeatedly over the next

three years: Are Women People, Mr. President? Miller's

first column framed an excerpt from a campaign speech in which Wilson

had promised to bring the 'Government back to the people' under a bold

headline that posed the question Miller asked repeatedly over the next

three years: Are Women People, Mr. President?

Miller's column quickly went viral and was moved from its somewhat

marginalised position on the Woman's Page to a more privileged place

beside the newspaper's editorials.

Just as young people today get their political news through comedy

shows like The Daily Show, 1910's New Yorkers turned to Miller's column

for witty analysis of the news.

Her funny, rhyming commentaries were catchy and memorable. The

question she posed became a campaign slogan. Her analysis of

contemporary politics not only made anti-suffragist politicians look

stupid. It also made her (and women like her) look completely capable of

participating in the political sphere.

When US Vice President Thomas Riley Marshall defended his

anti-suffragist position by saying "My wife is against suffrage, and

that settles me," for example, Miller penned this comic poem in

Marshall's voice:

'My wife dislikes the income tax, And so I cannot pay it; She thinks

that golf all interest lacks, So now I never play it; She is opposed to

tolls repeal (Though why I cannot say), But woman's duty is to feel, And

man's is to obey.'

Are Women People? also collected a regular feature, Campaign Material

from Both Sides: humorous lists that assembled apparently waterproof

arguments about ridiculous topics.

'Campaign Material' used quotation in order to expose the structural

illogic of some of the most frequently used arguments in the

anti-suffrage campaign. For example, 'Why We Oppose Pockets for Women',

lists eight reasons:

1.Because pockets are not a natural right.

2. Because the great majority of women do not want pockets. If they

did they would have them.

3. Because whenever women have had pockets they have not used them.

4. Because women are required to carry enough things as it is,

without the additional burden of pockets.

5. it would make dissension between husband and wife as to whose

pockets were to be filled.

6.?Because it would destroy man's chivalry toward woman, if he did

not have to carry all her things in his pockets.

|

www.shutterstock.com |

7.?Because men are men, and women are women. We must not fly in the

face of nature.

8.?Because pockets have been used by men to carry tobacco, pipes,

whisky flasks, chewing gum and compromising letters. We see no reason to

suppose that women would use them more wisely.

The poet laureate of the suffrage cause

Miller, a member of the legendary Algonquin Round Table, was best

friends with Harpo Marx, Clarence Day and Alexander Woollcott and the

founder of the Women's City Club.

Her work ranged from political commentary to middlebrow novels that

were routinely serialised, then made into Broadway plays, then used as

the basis for Hollywood films starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.

Miller's central preoccupation in her suffrage poetry was the

politics of voice: who speaks and for whom in the gendered public

sphere, as titles of poems such as 'What Every Woman Must Not Say', 'If

They Meant All They Said', and 'On Not Believing All You Hear' suggest.

Quotation and ventriloquism were her primary tactics, but she

occasionally wrote sincerely, as with the poem Chivalry:

'It's treating a woman politely As long as she isn't a fright: It's

guarding the girls who act rightly, If you can be judge of what's right;

It's being-not just, but so pleasant; It's tipping while wages are low;

It's making a beautiful present, And failing to pay what you owe.'

Throughout the 1910s, Miller wrote more than 300 sonnets, odes,

elegies, quatrains, limericks, and nursery rhymes about suffrage, many

of which were collected in 'Are Women People?' and its companion volume

'Women Are People!' (1917).

Voice of the president

It was perhaps fitting that after years of quoting and

ventriloquising anti-suffragists such as Woodrow Wilson, Miller was

given a rare opportunity to express her political views through the

voice of her political representative. In 1918, when the White House

desperately needed a ghostwriter to write speeches for Wilson, they

hired - you guessed it - Alice Duer Miller!

That the writer who had spent years critically quoting what the

President had said and ventriloquising what the President should have

said would find herself ghostwriting his speeches shows the hand Miller

had in bringing the government back to "the people" through her

campaigning for woman suffrage.

Through her witty books and the popular column they were based on,

Miller achieved a public voice even before she had the vote; among other

things, her public voice revealed women's fitness for full participation

in the public sphere, as both citizens and poets.

(The author is Professor of English, University of British Columbia

and this article was originally published in The Conversation. Are Women

People? a Book of Rhymes for Suffrage Times is available via the

Gutenberg Project) |