Cheated out of Rs 500,000 and a kidney

by Amantha Perera

One and half years ago, Johnson, a 20- something youth, hailing from

Sri Lanka's tea plantations, received an unusual request. The caller,

someone Johnson knew casually, made an offer for his kidney. "It was for

a half a million rupees (around US $3,500)," he said.

|

|

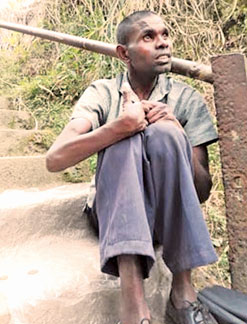

Rajendaran, a 24 year-old

beggar at the Talawakele railway station who gets regular

requests for his kidney but has so far refused. |

Johnson thought for a while and agreed. Mired in poverty and without

a permanent job, half million was something he could only dream about

till then. Soon he admitted himself into a private hospital in the

capital city, Colombo, about 170 km from his native Talawakele. Neither

did Johnson know anyone there nor was he familiar with the sprawling

urban maze.

After several tests, his kidney was deemed compatible with a 41

year-old man from the North of Sri Lanka, the only detail Johnson knew

of the man who now has his kidney. From the time he got admitted,

Johnson was well taken care of by his initial caller, a middle man. To

those who were curious, he was advised to tell them that he was a

relative of the kidney patient. No one asked, Johnson said later.

Johnson stayed in the hospital for several days after the operation.

When he returned home, he was provided a vehicle. But the benevolence

ended there. For days Johnson went to the bank and checked his account.

No monies had been credited. Nervous, he called the middle man; the

number returned a message that said it had been disconnected.

He visited the man's residence, only to be told that he had moved out

and was now overseas. "I did not receive a cent for my kidney," a

desperate Johnson said. He suspects that the middle man did in fact get

the cash, but decamped with it.

Johnson's story may be unusual in other segments of Sri Lanka society

that are richer and savvier. But among the estate community in the

central hills, selling a kidney has now become a frequent tale of woe.

Mahendran, a 53 year-old father of four, is also a victim of the same

racket. He received a request for his organ while working as a helper at

a rich household. It was the same modus operandi: a middle man, known a

little but not that much, approached Mahendran, made the play for the

kidney and got his consent.

Both thereafter travelled to Colombo, where Mahendran like Johnson

was a fish out of water. At the hospital he was asked to pretend to be a

relative of the patient. Mahendran also got played out after he had

parted with his kidney. "I was promised Rs 150,000 ($1,050) and paid Rs

10,000 ($70)."

Mahendran said he initially balked at selling his organs, but finally

gave way because of abject poverty. "I have four children to look after,

that was why I did it," he said.

Now with one kidney, he can't work hard and earn as much as he used

to. Two of his eldest kids, two boys have now dropped out of school.

Both men said that poverty was the main factor behind their decision.

Sri Lanka's plantations, where the island's popular tea is grown, has

been mired in poverty. According to the Government's Census and

Statistics Department, over 15 per cent of the population lives below

the poverty line, in some areas the rate is close to 30 per cent.

However, there are no statistics on the large-scale trafficking

racket. Officers at the Talawakele Police station say they have heard

about the sale of the kidneys but no complaints have been lodged.

There could be several reasons for the lack of police complaints.

Both Mahendran and Johnson said they have now become the butt-end of

village jokes. Another is that according to Sri Lanka's Penal Code

anyone who sells an organ faces a jail term of seven years.

Clearly, this issue warrants closer investigation. Prabash

Karunanayake, a doctor at the Lindula hospital in Talawakele has had to

regularly admonish villagers who have sought advice on parting with a

kidney. "In recent days I have had to warn at least three persons on the

dangers they court by doing this," he added.

Another one who has had to deal with such offers is Rajendaran, a 24

year-old beggar, who lives and begs at the Talawakele railway station.

He said that several people have made offers for his kidney which he

says have now become routine. "I have refused all of them so far. I

don't want to make a complaint because these are dangerous people."

Kanapathi Kanagaraja, a member of the Central Provincial Council,

feels that before the sale of kidneys acquires larger proportions, the

government should take decisive action to stem it.

"We will take this up at provincial level, but it warrants national

level attention."

Prathiba Mahanama, the former head of the national Human Rights

Commission said that till national level programmes are launched, the

most effective deterrent is public awareness.

That is a view that Karunanayake, the area doctor, also agrees on.

"Right now because people don't know the medical dangers, the sale of

kidneys is purely a financial transaction.

People are unscrupulously making such offers because they know that

at the right price, a kidney can be bought."

- IPS

|