|

Anna Kavan (1901-1968)

An extraordinary life

The first time I read anything by Anna Kavan was a short excerpt ‘A

Visit’ – from her book ‘Julia and the Bazooka’ published posthumously in

1970 – two years after she died.

“One hot night a leopard came into my room and lay down on the bed

beside me. I was half asleep, and did not realise at first that it was a

leopard.

|

Anna Kavan |

I seemed to be dreaming, the sound of some large, soft-footed

creature padding quietly through the house, the doors of which were wide

open because of the intense heat.

It was almost too dark to see the lithe, muscular shape coming into

my room treading softly on velvet paws, coming straight to the bed

without hesitation, as if perfectly familiar with its position.

“A light spring, then warm breath on my arm, on my neck and shoulder,

as the visitor sniffed me before lying down.

It was not until later, when moonlight entering through the window

revealed an abstract spotted design, that I recognised the form of an

unusually large, handsome leopard stretched out beside me.

“His breathing was deep though almost inaudible. He seemed to be

sound asleep. I watched the regular contractions and expansions of the

deep chest, admired the elegant relaxed body and supple limbs, and was

confirmed in my conviction that the leopard is the most beautiful of all

wild animals ... While I observed him, I was all the time breathing his

natural odour, a wild primeval smell of sunshine, freedom, moon and

crushed leaves, combined with the cool freshness of the spotted hide,

still damp with the midnight moisture of jungle plants.

I found his non-human scent, surrounding him like an aura of

strangeness, peculiarly attractive and stimulating.

My bed

“My bed, like the walls of the house, was made of palm-leaf matting

stretched over short bamboos, smooth and cool to the touch, even in the

great heat.

It was not so much a bed as a room within a room, an open staging

about twelve feet square, so there was ample space for the leopard as

well as myself.

I slept better that night than I had since the hot weather started,

and he too seemed to sleep peacefully at my side.

“The close proximity of this powerful body of another species gave me

a pleasant sensation that I am at a loss to name.

“When I awoke in the faint light of dawn, with the parrots screeching

outside, he had already got up and left the room.”

|

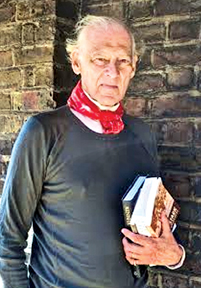

Sir Christopher Ondaatje (OC, CBE) |

Reading this sensuous story prompted me to delve into her

extraordinary life. Wanting to be judged solely on her creative output –

which was considerable – she destroyed almost all of her personal

correspondence including her diaries except for a short eighteen-month

period.

Changed her name

She changed her name, doctored her records with intent to mislead,

and anticipated becoming the “world’s best-kept secret: one that would

never be told.” She almost succeeded.

Anna Kavan died on December 4, 1968 putatively of heart failure but a

victim of a lifetime’s addiction to heroin. She had been preparing to

inject herself with a shot of the liquid, which was still in the barrel

of the syringe.

The plunger had not been depressed and she collapsed with the needle

in her arm. She had a long history of attempted suicide and a propensity

as a serious user to overdose.

Nevertheless she was a gifted writer and a talented painter who

endured an unhappy childhood, two failed marriages, and a long mutually

dependent relationship with her psychiatrist.

She was born Helen Emily Woods on April 10, 1901 in Cannes and in the

first of a series of familial rejections was sent away soon after she

was born to be cared for by a nurse, before returning to live with her

parents in West London.

Denied any parental affection (she was allowed to see her mother for

ten minutes each evening before dinner) - she was harshly introduced to

the emotionally cold world that would adversely affect her for the rest

of her life.

When she was six she was sent to an American boarding school, where

for the next seven years she suffered an excruciating sense of betrayal,

alienation and acute loneliness.

American boarding school

She was often left in the school during holidays. When she was

fourteen her father killed himself, after which her mother reacted

against the social stigma of suicide by removing her from her American

boarding school and sending her to others, first in Switzerland and then

in England.

Four years later she was offered a place at Oxford but her socially

scheming and egotistical mother dissuaded her from accepting the place

and instead forced her to marry the lascivious Donald Ferguson, who was

twelve years her senior and who took her to Burma, where he was an

engineer on the railways. It was a disastrous decision both

psychologically and sexually, which led in time to her extreme reaction

against social convention.

She began writing and gave birth to her son Bryan during her

short-lived and explosive marriage to the alcoholic Ferguson. In 1923

Kavan left Ferguson and returned to the UK with her son. Living alone in

London in the mid-1920s she began studying painting at the London

Central School of Arts and Crafts and continued painting throughout her

life.

|

An illustration for her leopard story ‘A Visit’ |

Eventually she published six novels under her married name Helen

Ferguson between 1929 and 1937, some of it about her tropical hell in

Burma. But first, there was a new relationship and possible, though not

recorded, marriage to another bohemian alcoholic Stuart Edmonds of

independent means. She was now using cocaine heavily to compensate for

the messy relationship, which also ended before the 1940s.

As part of her desire in later life systematically to eliminate the

facts of her past Anna Kavan destroyed everything she recorded about her

troubled life, and in the twenty-five years in which she lived under the

alias of Anna Kavan, she expressed little or no interest in the novels

she had published. From the 1940s onwards Anna Kavan, a name she took

from one of the fictional characters in her 1935 novel ‘A Stranger

Still’, had no room in her life for Helen Ferguson.

What followed was a tortuous addictive life involving numerous

relationships before she embarked on a long inseparable telepathic bond

with her psychiatrist Dr Karl Theodor Bluth, who advocated the use of

drugs as an incentive to poetic vision.

Kavan’s dependency on Bluth, not only as the source of her privately

scripted heroin but an inseparable friend ended only on his death in

1964. The trust of this unusual relationship even extended to their

having agreed on a suicide pact.

Kavan’s numerous breakdowns, serious suicide attempts, devoted

attraction to gay men, phobias, obsessions, hospitalisations,

impoverishment, loneliness and courage was none the less compounded by

the need to write and her work is now admired for the intensity of its

vision by novelists as different as J.G. Ballard and Doris Lessing.

Certainly the publication of her masterpiece ‘Ice’ in 1967, a year

before she died, helped considerably to enhance her literary reputation.

In her last years she finally intersected with an audience receptive to

how she saw the world. Her niche in cult literature is secure, and this

is how she would have wanted to be remembered.

She had no wish to be identified by facts and there is little doubt

that she would have rejected the inevitable biography ‘A Stranger on

Earth’ authored by Jeremy Reed and published in 2006 of the acclaimed

but esoteric author.

(Source: The Sri Lankan ANCHORMAN, Toronto, Canada) |