Ecstacy and agony:

Kandy’s glorious drummers and dancers fight

poverty and caste stigma

By Isuri Yasasmin Kaviratne

Uttama muni Dalada Wadammana

Mok pura ran nauka – balan saki

Sath samuduru gembare...

[Friend, behold the sacred, noble, tooth relic being brought

across the seven seas in celestial golden ships.]

– Dharmadasa Walpola

|

|

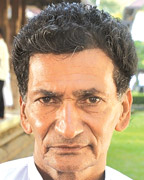

Peter Surasena with his three sons |

Thousand-year-old art forms, today, they are still performed as a

service - once feudal - to the great Maligawa, the Palace. They are also

an enduring practice of spiritual devotion where you commit yourself

unconditionally to the service of the holy – the Sacred Tooth of the

Buddha. This is the aura, the identity, of the dancers, drummers and

other traditional musicians of the Kandy Esala Perahera.

|

|

(Pix: Gamini Ranasinghe) |

These artistes, numbering in the hundreds, are immersed in both

sacred rite as well as the grandeur and pride of their performance in

the annual pageant at this time of the year. And bound by centuries-old

custom and training, it is a performance of integrity to the art and to

their faith. To all appearances it is a reverential, often spectacular,

performance in a magnificent event.

Or, so it seems, until one peeps into the lives of this cohort of

artistes to observe the struggle the traditional families go through to

maintain a millennia-old commitment but under modern socio-economic

circumstances very different from that of the ancient society.

Livelihood

For some, it is, directly, a challenge of income and livelihood. For

others, it is the social context that discourages the younger generation

from entering the traditional profession of their ancestors. For yet

others, it is the lack of assurance that these traditions will survive

the next fifty years. Some blame society, some blame the economy, some

blame the State for not looking after the traditional performers.

Many of the traditional dancers, drummers and other performers of the

Sri Dalada Perahera confidently date back their services to the Maligawa,

to the late medieval Dambadeniya Kingdom, the era of King Parakramabahu

II.

Four main traditional families are in charge of the drummers who

perform at the Perahera. O. P. Karunadasa from Uduwela family, is the

drummer who leads the drummers at the Maha Perahera, a job performed by

his father and grandfather before him. He says his life is dedicated to

the Maligawa, being the Chief Panikkirala, and assumes duties with

pride. “It is our duty to accompany the Karanduwa and as long as it is

on the roads, we stay close to it.” He explained that even if an

elephant starts behaving wild, the only people who are not allowed to

run for safety are the four Chief Panikkiralas and the Diyawadana Nilame,

whose job is to ensure the safety of the Sacred Tooth of Buddha.

Parading with him is G. A. Molagoda from the Molagoda family, who

admitted that their troupes are feeling the financial pressure that

their fathers and grandfathers were not subjected to. The Ninda Gam, the

villages ancient kings assigned for the traditional families to benefit

from their income, are not in use any more. Molagoda said, most of the

Ninda Gam are situated in Kurunegala and Matale districts and the

dancers and drummers are not in a position, financially and socially, to

frequent them. “Once upon a time, their ancestors might have got an

income from these lands but the world doesn’t function the same way

anymore. Most of these lands are now home to encroachers.”

|

|

"We too have

committed our lives to the perahera, and we do so with the same

pride and honour as our father did...

It has become the most important objective in our lives, and we

commit ourselves to it”

– Peter Surasena |

The main occupation of these performers when Perahera is not in

season, is to sell flowers near the Maligawa. For those who take part in

the daily Thewawa, the drumming for the morning and afternoon religious

rituals at the Maligawa, are being paid for, but the others have

resorted to the flower business for their survival.

Introducing the Diyawadana Nilame to the audience, it is the Kandyan

dancers headed by Peter Surasena and his sons. They consider themselves

especially blessed for they are the performers that introduce, the

Kandyan dancers whose position in the Perahera is placed in between the

Karanduwa and the Nilame. Though financially more stable than their

fellow performers, Surasena is concerned with what the future might

bring to traditional dancers.

Kandyan dancing is not, in theory and practice, a dance that was

originally performed for parades. It was first performed as a

Shanthikarma, to cure the curse placed on King Vijaya that was

transferred to King Panduwasdevu after the death of the former. The

traditional Perahera dancers have mastered the techniques of performing

for two audiences on either sides while being on the move. Suresena

said, his team has the additional task of performing for four audiences;

people on either sides, the Diyawadana Nilame behind them and the

Karanduwa in front of them. However, it is this techniques the new

performers lack, though they are fully equipped with the theoretical

knowledge, he added.

Another life

|

|

"It is our duty to

accompany the Karanduwa and as long as it is on the roads, we

stay close to it.” He explained that even if an elephant starts

behaving wild, the only people who are not allowed to run for

safety are the four Chief Panikkiralas and the Diyawadana Nilame.

– O.P. Karunadasa |

Susantha and Janaka Surasena are the two elder sons of Peter Surasena,

who have taken up the task of leading their troupe at the Perahera. Born

to such a family, living their lives around the excitement the season

brings, the duo claim they never knew another life, or wanted to seek

riches elsewhere. “We too have committed our lives to the perahera, and

we do so with the same pride and honour as our father did,” Janaka said.

The younger generation however, has realised that though they value the

life of a dancer, it will not be enough to live a comfortable life.

Janaka is an employee of the Nestle Company who, he said, have been

supportive of his performances, especially, during this season. Susantha,

who lives in Japan, visits Sri Lanka every year, to take part in his

family tradition.

“It has become the most important objective in our lives, and we

commit ourselves to it,” Susantha admitted.

Though the Surasenas are financially stable, they admit that many

dancers find survival difficult in the open economy and said better

support from the state would be welcomed.

As a society, the traditional dancers are not respected, though

during the days of the kings, they were treated with reverence, their

performances appreciated as well as their commitment to maintain this

centuries old tradition. Today’s society doesn’t give any assurance that

this art will prevail in the years to come, he said. Janaka’s son,

Suchira Nayanaja is one of the youngest dancers at the Perahera.

The 11 year old has been performing in the Perahera for three years

and has the same sense of pride his father and grandfather cherish about

their traditional lives. However, Janaka admitted that he is not sure

whether his son will be compelled to give up performing due to financial

reasons, when it is his time to settle down and start a family.

There are many government servants who apply for leave to perform in

the Perahera. Galagedara Samansiri is a graduate from the University of

Performing and Visual Arts and a teacher who preferred his traditional

family name, Kondadeniye Saman, as opposed to the village name given to

him instead.

Agreeing with Surasena, he admitted that what he learnt at the

university is no match for the knowledge he gained from his father and

grandfather and that’s the knowledge and practice he uses when

performing for the Perahera. “Here, about to perform in the Perahera,

I’m not better than anybody else, because I have a degree. Everyone is

equal with the traditional knowledge passed on to them.”

As a teacher, he earns a monthly salary, and knows his future is

secure with a pension after retirement, but he is sympathetic towards

his fellow dancers who do not have that luxury. “My main drummer doesn’t

have a proper house to live in, but has spent his whole life performing

this great art. These economic constraints have discouraged many

traditional dancers.”

|

|

"Once upon a time,

their ancestors might have got an income from these lands but

the world doesn’t function the same way anymore. Most of these

lands are now home to encroachers.”

– G.A. Molagoda |

The perahera tradition is such that, after the Maha Perahera done by

the Maligawa, the four devala peraheras take to the roads, with their

respective Nilames.The Chief Panikkirala of Vishnu Devalaya is 21 year

old A. G. Saman Priyantha, who has, from an early stage in life,

committed himself to the traditions of his forefathers. However, his

father B. Piyadasa claimed, though happy, it was not his intention that

his son follow in his footsteps. Therefore, he took precautions to

protect him from the social stigma he might suffer due to his caste. The

ancient drummer caste, being positioned low in the oppressive caste

structure of the feudal social system, brings with the caste name, even

today, a most discouraging social stigma. So Piyadasa took the

precaution of giving his son a different family name.

“I was not sure what he would decide to do in his life, so I didn’t

want to give him my name, in case it’ll be a hindrance to advancements

in his life. I gave him the name of our village instead.” According to

Piyadasa, the social stigma is strong enough to forego the family name

in the generations to come. However, Saman is proud to be part of the

family of B. Piyasada, B. Kiri Ukkuwa and Balaya, his father,

grandfather and great grandfather. Piyasada only hopes that this

tradition would survive after his son.

Financially, he said, they are not well off. There are lands assigned

for them, but they hardly generate any income. The ancient payment

methods do not work in the modern days, and said they are thankful that

the administration of the Vishnu Devalaya has allowed them to run a

small shop, just outside the main entrance to the Devalaya, from which

they gain a daily income.

Meanwhile, Sri Dalada Maligawa assured that they do look after the

performers. Jayampathy Weddagala, the Cultural Secretary of Sri Dalada

Maligawa said, all the performers get a payment of Rs. 1,000 – 1,200 per

day during the season, together with accommodation close to the Maligawa.

He added that medical facilities are available for the performers during

this period.With a large number of performers taking part, the leaders

of each team is given the money, which they distribute among themselves.

“They are given special monetary gifts too, after the Perahera season.

Individually, they may have problems, but it is impossible to address

them. We do everything in our power to take care of them.”

|

|

|

|

|

| B.

Piyasada with his son |

A. G.

Saman Priyantha |

Kondadeniye Saman |

Janaka

Surasena with his son Suchira |

He said, the recent initiative to start a dancing academy for the

young boys and girls from traditional families is one of them. The new

academy would provide a good platform for the youngsters to learn the

art of traditional dancing and they can study up to degree level at the

Academy.

The Ninda Gam are not bringing any income, Weddagala said. One reason

for it is the dancers stopped visiting those lands, and cultivating

them. “Without putting an effort, it is difficult to expect an income,”

he added.

The Ministry of Cultural Affairs was not available for comment

despite several attempts to reach them. |