|

Cryptozoology -

Myth or Fact?

by Jayasri Jayakody

The search for animals that are rumored

to exist, but for which conclusive proof is missing is known as

Cryptozoology. This includes the search for living examples of animals

that are known to have existed at one time, but are considered to be

extinct today.

Those who study or search for such animals are called

cryptozoologists, while the hypothetical creatures involved are referred

to by some as "cryptids", a term coined by John Wall in 1983.

Invention of the term cryptozoology (adding the Greek prefix krypt¢s,

or "hidden" to zoology to mean "the study of hidden animals") is often

attributed to zoologist Bernard Heuvelmans. However, Heuvelmans himself

attributes coinage of the term to the late Scottish explorer and

adventurer Ivan T. Sanderson.

Heuvelmans argued that cryptozoology should be undertaken with

scientific rigor, but also with an open-minded,

|

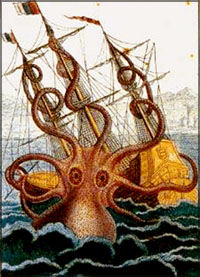

Kraken attacking a ship

|

interdisciplinary approach. He also stressed that attention

should be given to local and folkloric sources regarding such creatures;

folktales may indeed contain grains of truth and important information

regarding these animals while often layered in unlikely and fantastic

elements.

Some cryptozoologists align themselves with a more scientifically

rigorous field like zoology, while others tend toward an anthropological

slant. Cryptozoology is often considered a pseudoscience by mainstream

zoologists and biologists.

Scientists have demonstrated that some creatures of mythology, legend

or local folklore were rooted in verified animals or phenomena. Thus,

cryptozoologists hold that people should be open to the possibility that

many more such animals exist.

In the early days of western exploration of the world, many native

tales of unknown animals were initially dismissed as superstition by

western scientists, but were later proven to have a real basis in

biological fact.

There are several animals cited as examples for continuing

cryptozoological efforts:

The Coelacanth, a "living fossil" - a representative of an order of

fish believed to have been extinct for 65 million years - was identified

from a specimen found in a fishing net in 1938 off the coast of South

Africa. (Unknown to scientists the coelacanth was well known to Comoros

fishermen as the Gombessa.)

Similarly cited is the 1976 discovery of the previously unknown

megamouth shark, discovered off Oahu, Hawaii, when it became entangled

in a ship's anchor. While the Megamouth is not a useful analogy to

support the existence of marine "cryptids" in general, it does

demonstrate the resistance of science to identify new large species of

marine animals without a corpse.

Sightings of Megamouths now number approximately one a year. Before

the discovery, one could argue this consistent sighting record was also

present, but that the sightings were ignored or discredited as of some

other animal.

Also cited is the 2003 discovery of the remains of Homo floresiensis,

a descendent of Homo erectus which took the anthropological community

completely by surprise.

Legends of a strikingly similar creature, called Ebu Gogo by the

local people of Flores, persisted until as late as the nineteenth

century, but it took until 2003 before the possible fossil remains of

this species were found. In addition, human folklore is full of

references to small forest people, called dwarves, elves, fairies,

gnomes or leprechauns.

In 1930, a Danish research ship, the Dana, collected a 6-ft eel-like

larva. Typically, a 3-in (7.6-cm) eel larva (called a leptocephalus)

grows into a 6-ft (1.82-m) eel, and therefore scaling up, a 6-ft larva

may result in a 100-ft (30-m) adult.

Cryptozoology supporters have noted that many unfamiliar animals,

when first reported, were considered hoaxes, delusions, or

misidentifications. The platypus, giant squid, mountain gorilla,

grizzly-polar bear hybrid, and Komodo dragon are a few such creatures.

Supporters claim that unyielding skepticism may in fact inhibit

discovery of unknown animals, and skeptics claim that skepticism

prevents an unwarranted potential epidemic of misidentified animal

sightings being successfully attributed to cryptids.

The emblem of the now-defunct International Society of Cryptozoology

is the okapi, a forest-dwelling relative of the giraffe that was unknown

to Western scientists prior to 1901.

The notion that some cryptids are too strange to be real has been

countered by the fact that people describe based on what they know.

For instance, early explorers in Australia described kangaroos as

creatures that had heads like deer (without antlers), stood upright like

men, leaped like frogs, and sometimes had two heads, one on top and

another on the stomach.

Similar is the giraffe, which was thought by many ancient cultures to

be a mix of parts from the camel and the leopard. This misconception

lives on in the giraffe's scientific name: camelopardalis, or

"camel-leopard."

Many cryptozoologists strive for legitimacy - some of them are

respected scientists in other fields - and discoveries of previously

unknown animals are often subject to great attention.

However, cryptozoology per se has never been fully embraced by the

scientific community.

A cryptozoologist may propose that an interest in reports of animals

does not entail belief, but a detractor might counter that accepting

unsubstantiated sightings without skepticism is itself a belief.

As in other fields, cryptozoologists tend to be responsible for

disproving their own objects of study. For example, some

cryptozoologists have collected statistical data and studied witness

accounts that challenge the validity of many Bigfoot sightings.

Many mainstream experts are likely put off by the more

sensationalistic fringe elements in cryptozoology, and the occasional

overlap with alleged paranormal phenomena.

Another reason for the lukewarm reaction from mainstream science may

be a lack of specialisation. Unlike mainstream animal experts (who

typically focus very narrowly on a specific species for their study),

many cryptozoologists study or research a broad range of alleged

creatures from many different families.

Most criticism-and sometimes ridicule-from the scientific mainstream

is, however, directed at the proponents for the existence of the more

"famous" mega-fauna cryptids (like Bigfoot, Yeti or the Loch Ness

Monster), whose existence is generally regarded as highly unlikely.

A cryptozoologist must also address the sudden appearance and

disappearance of sightings of the proposed animals, for example the Loch

Ness monster was not commonly reported until the 1930s.

In the nineteenth century, a Swedish folklorist collected trustworthy

reports of sightings of lindworms in Smaland, Sweden, but after a reward

for a real animal was proclaimed, not only did anyone fail to find a

lindworm, but the reports of existing such creatures rapidly decreased

and disappeared entirely.

The portrayal of the Loch Ness Monster's form appears to have changed

radically between early sightings and the discovery of the plesiosaur.

In addition, the beginning of modern sightings at Loch Ness began when

the lake was connected to the ocean by series of canal locks.

Other myths and rumours coming from North America and Latin America

drive us towards legendary beasts such as the Chupacabra and Caneratto,

fantastic creatures of the night whose origin is still unknown. |