A walk through Pettah

Within walking distance of Colombo's glamorous five-star hotels is a

quadrangle of streets known as Pettah, where the heart of Colombo's

mercantile community throbs vigorously. In an area of six street blocks

east, by four blocks south, are shops selling every object imaginable -

and some totally unimaginable. Within walking distance of Colombo's glamorous five-star hotels is a

quadrangle of streets known as Pettah, where the heart of Colombo's

mercantile community throbs vigorously. In an area of six street blocks

east, by four blocks south, are shops selling every object imaginable -

and some totally unimaginable.

To feel the pulse of the city, or simply to find and odd souvenir, a

visitor need only take a walk through Pettah. It's a thrilling

experience that gives an instant insight into what makes Sri Lanka tick,

yielding more fascinating glimpses of local life in a morning's walk

than does a week's touring the country by air-conditioned bus.

Certainly no tour bus could ever negotiate the street of Pettah.

Thery're filled with shoppers, shops filled to overflowing - so goods

have to be stacked on the sidewalk, lorries unloading produce from

upcountry villages or imported goods from the port, and porters pushing

barrows packed high with boxes.

Taxi and even three-wheeler drivers have been known to refuse to take

tourists to Pettah simply because, once inside, it could take a vehicle

a day to get out, because of the clogged traffic and warren of one-way

streets.

Walking through Pettah may be hot, but it's rewarding and safe.

People in Pettah are far too busy minding their own business to bother

about a stranger. If visitors stop to bargain they'll be treated

courteously, even though they're spending only a few rupees.

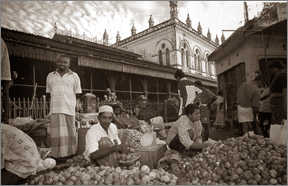

Pettah is the entrepot for the whole of Sri Lanka. Villagers come

here to purchase household implements, wholesalers store everything from

scrubbing brushes to expensive computers, textile traders lurk behind

bolts of brilliant-hued fabric piled high on wooden counters, jewellers

and gem merchants quietly conduct deals worth a fortune, while

fruitsellers shout about their wares and wayside vendors of junk wait

patiently for customers. Pettah is the entrepot for the whole of Sri Lanka. Villagers come

here to purchase household implements, wholesalers store everything from

scrubbing brushes to expensive computers, textile traders lurk behind

bolts of brilliant-hued fabric piled high on wooden counters, jewellers

and gem merchants quietly conduct deals worth a fortune, while

fruitsellers shout about their wares and wayside vendors of junk wait

patiently for customers.

Pettah lies beyond what is still known today as Colombo Fort. The

bastions have gone but when the Dutch planned the city in the 17th

century, they designated the area east of what is now Lotus Road as a

residential zone.

The British, who arrived in the 18th century with Madras-trained

civil servants and South Indian lexicon, called this residential area

Pettah. Derived from the Tamil word, pettai, it's an Anglo-Indian word

used to indicate a suburb outside a fort. Today, the Sinhalese phrase,

pita-kotuwa (outside the fort) conveniently describes the same place.

The transition from a housing estate to a thriving market bazaar took

place as the British decided to build homes further from the Fort in the

more salubrious area of Cinnamon Gardens, now Colombo 7. Pettah became

Colombo 11, still an unfashionable address; Fort is Colombo 1.

Writing in 1900 in his book Golden Tips, Henry W. Cave called Pettah,

"the native traders' quarter." He wrote, perceptively: "European

residents in Ceylon, as a rule, dislike passing through purely native

streets, but the traveller finds many attractions in them, and is

usually more interested by a drive through Pettah than any other part of

Colombo." He explains why. "The visitor for the first time becomes a

witness of the manners and customs of oriental life."

Forty years before, Sir James Emerson Tennant commented in his book

Ceylon that the shops in Pettah "are certainly amongst the wonders of

Serendib, from the habits of their owners and the multiform variety of

their contents. Here everything is procurable that industry can collect

from the looms of Asia and the manufactories of Europe..."

It's amazing that, while fashions have changed and window-fronted

shops have replaced merchant godowns, Pettah still bustles with the same

urgent commerce and vitality. The walk from the Fort is sultry and

gentle at first, which makes the clamour and chaos of Pettah all the

more thrilling.

Domed buildings remaining from the Victorian era line the port side

of the road (Sir Baron Jayatilaka Mawatha) that leads to Pettah's main

street. Lotus Road, which was named after the lotus pond created by the

Dutch as a space between the Fort and Pettah, and was later filled in by

the British, links it. Domed buildings remaining from the Victorian era line the port side

of the road (Sir Baron Jayatilaka Mawatha) that leads to Pettah's main

street. Lotus Road, which was named after the lotus pond created by the

Dutch as a space between the Fort and Pettah, and was later filled in by

the British, links it.

The first of the streetside stalls line the landside of the road, but

these are genteel compared with the bustle deep inside Pettah. The

entrance is marked formally by a tall monument in the centre of a

roundabout.

Known as the Khan Clock Tower, it was erected in 1923 to commemorate

the life of a now-forgotten grandee, Framjee Bhikkahee Khan, by his sons

on the 45th anniversary of his death. To its right, Front Street runs

southwards as the western border of the rectangle forming Pettah.

Main Street is the northern boundary; it used to join the harbour

waterfront, but now lies two blocks away from the reclaimed land of the

modernised port. The only exit from Pettah in the 19th century was

through Kayman's Gate at the eastern end of Main Street.

The bell tower of the gate still stands, barely visible behind shops

and an electricity transformer. It gained its name from the crocodiles -

caymans - which dwelt in the moat that once encircled that part of

Pettah. A drawbridge gave access to the road to Negombo. Main Street is

the upmarket part of Pettah.

Its shops specialise in general goods including gigantic cooking pots

and radiant saris. The sidewalk is crammed with the makeshift stalls of

itinerant vendors of odd knick-knacks, such as bouncing coils of wire

and lurid, furry puppets.

Five streets, each called Cross Street, run parallel to Front Street,

linking Main Street with Pettah's southern boundary of Olcott Mawatha.

That street provides access from the Colombo Fort railway station and is

named after Henry Steet Olcott, an American-born Buddhist crusader whose

statue stands in the station car park.

Each of the Cross streets has stores specialising in certain

commodities. First Cross Street is the repository of electrical goods,

Second Cross Street is renowned for textiles and tailoring. Front Street

is good for suitcases and musical cassettes.

Walk through the jolly throng of people and traffic to where Main

Street spills into the junction with Sea Street on the left and the old

Town Hall on the right. A clutch of vendors of spare parts salvaged from

every kind of machine - from ceiling fans to computer innards - brood on

the pavement. Behind them are railings guarding a cobbled, open-sided

courtyard which is, surprisingly, the Municipal Museum.

On display are bygones of city life, such as cast-iron water pumps

and drinking fountains, a manhole cover, a city father's official robes,

a massive steamroller and an ancient stream lorry emblazoned with the

council's crest.

The Town Hall was built by the British in 1873 and remained the seat

of the municipal council until 1928, when the city fathers removed

themselves to the grander surroundings of Cinnamon Gardens. Stand for a

few minutes to study the building's exterior. The mix of minarets

crowning its roof is a 19th-century Western architect's flamboyant

acknowledgement of its Eastern location. A magnificent double-coach

portico shelters its entrance.

Step inside and a cheerful custodian pops up from an inner office to

guide you around. A grand wooden staircase leads up to the council

chamber, where stuffed effigies of the participants at a 1906 council

meeting sit around a huge table.

Outside the town hall, Sea Street is a clutter of signs in Sinhalese

and Tamil advertising the many family-owned gem and jewellery shops.

Shoppers there seem more elegant than those in nearby Gabo's Lane,

which is the preserve of merchants selling dried herbs by the sackful to

the practitioners of Sri Lanka's natural medicine, ayurveda.

Behind the Town Hall, in a converted auditorium, are shops dealing in

traditional household implements that would make unusual souvenirs:

wooden coconut scrapers, coconut shell ladles, doormats made of coir

(coconut-husk fibre), swizzle sticks, sieves and wooden kitchen gadgets.

The tall building, standing gaunt against the peerless blue sky

glimpsed from the back of the old Town Hall, was once the gas works.

Walk south towards it down any of the cross streets, across Keyzer

Street and into Prince Street.

There, defiant amid the motorbikes and cars parked in front of it -

and incongruous beside the bustle of street trading - stands an isolated

relic of the days when Pettah was a prime residential district.

With its tall white columns and flag-stone veranda, this was the home

of the Dutch Governor, Thomas van Rhee (1692-1697). This fine house

became the property of the Dutch East India Company before passing in

1776 to the British, who turned into a military hospital.

While all around it was changing, the house survived, becoming

variously an armoury, a police-training centre, and the Post and

Telegraph Office. It seemed doomed to decay until it was rescued in 1977

and restored to become a museum devoted to the Dutch period.

Courtesy Serendib

|