China protects its crops

At 5 o'clock on the morning of April 18, 1958, the few western

expatriates in Peking (Beijing) were jerked out of their beds by a

frightful din: shouts, explosions, harshly - shouted orders, al mingled

together. What on earth was afoot? A revolution! A riot, perhaps!

No-nothing of the sort. It was a sparrow hunt.

In Peking, in three days and nights, some 750,000 sparrows perished.

How many more died throughout the country during the macabre hunt when

the whole country was mobilized for it? Many millions, without doubt!

However, after the 72-hour long mass slaughter came to an end, the

government declared that it was a complete success and one of the four

scourges of China had been eliminated by the people.

|

“Operation Sparrow” |

According to posters displayed all over Peking, the four scourges

were the rat, breeder of diseases; the mosquito, bringer of Malaria, the

housefly, responsible for many a sickness, and the sparrow.

What was the sparrow accused of? Being extremely numerous, living

entirely on grain, and contrary to the old belief of being a voracious

feeder. In accordance with government publications and the Chinese media

a single sparrow eats 5 1/2 pounds of corn a year, thus a million of

them consumed each year 2,500 tons of seed corn. For a country with a

high rate of population growth and having to feed more hungry mouths

year by year, the sparrow was a pest to be disposed of, at any cost.

But, how were they to be destroyed? Shooting was impracticable as

gunpowder was expensive, even though gunpowder was supposed to have been

invented in China. In the mean time, a Russian scientist announced that

sparrows could not fly for 2 to 3 hours nonstop, before they fall

exhausted to the ground. The Chinese authorities decided to put this

theory into practice.

At length a major propaganda campaign was launched, aimed at

mobilizing the entire population for the battle. Orders were soon issued

making it imperative for everyone to participate, irrespective of sex,

age or physical standing.

On the anticipated day (April 18) and hour (5 a.m.)

"Operation-Sparrow" took off the ground. From the small hours noisy

crowds swarmed the streets of Peking. Submitting to orders of the

government or those in command of streets and housing schemes, or the

stern calls of street loudspeakers and the radio, the whole population

of Peking left their houses.

The milling crowds if men, women and children banged at metal pans,

set off fire-crackers, raised old broom handles or sticks with rags

tight to them at the flocks of birds flying above, all the while

shouting at the top of their voice (certainly, the Chinese are past

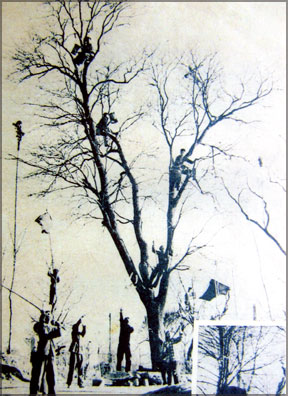

masters at this) Enthusiastic young men climbed on to roof tops or

nearby trees, while the others remained in the streets or squares, home

gardens and the open places, keeping up the halloo in unison. There

common endeavor was to prevent the sparrows from alighting on roofs and

the branches of trees.

The students of schools tried to bring down the birds on the wing

with slings and catapults, which had been distributed to them by the

teaching staff. The members of the Diplomatic Missions accredited in

Peking joined the hunt with shotguns in hand from the premises of their

respective embassies.

At the end of 48 hours of excitement and clamor, the exhausted

sparrows began falling to the ground in large numbers. No sooner than

they touched the ground men, women and children rushed up and dispatched

the unfortunate creatures with the sticks and brickbats that were in

readiness in their hands.

This went on for 72 hours during which no resident of Peking had a

wink of sleep, including those physically unfit. If the sparrows fell

from exhaustion their hunters too were on the point of doing so.

Some slipped from roofs or trees, and ended up with broken limbs,,,

but the zeal of the others remained unflagging.

On April 21, orders went out to stop the hunt, and the whole city

became strangely calm and quite, while parades were organized to show

off the trophies of the chase. The final balance sheet of the hunt,

which was conceivable under an authoritative regime showed a credit in

the sense that the sparrows simply disappeared from the Chinese scene.

But was the ultimate aim- a better harvest- achieved?

This is the sort of question to which one can get no answer. And even

if one could, what is it now to the sparrows?

A western journalist domiciled in Peking at the time commented in his

story thus, "It is difficult to know exactly what goes on in China,

because the political propaganda gives quite contradictory accounts.

It is true that it was realized somewhat later that the sparrows also

played a useful role in destroying the insects harmful to crops and so

any mass extermination of them was an error of judgment, besides being a

piece of criminal stupidity." |