I

n

t

h

e

l

i

m

e

l

i

g

h

t |

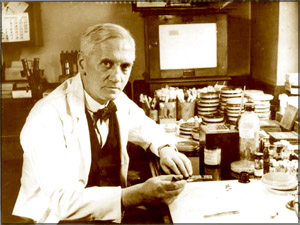

Alexander Fleming:

He discovered the life-saving 'wonder drug'

There

are occasions in the lives of all of us when we fall sick and have to

take some type of antibiotic.

How did this thing known as an antibiotic, which is so important to

us, come about? If you have heard of Sir Alexander Fleming, you would

know that he is the person who is credited with the discovery of

penicillin, the first antibiotic.

Although he was not single-handedly responsible for this discovery,

his name is the most famous one associated with the discovery of this

'wonder drug'.

Although the separation of the substance penicillin from the fungus

Penicillium notatum in 1928 brought Fleming and his collegues, Florey

and Chain, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945, this is

not the only achievement of this Scottish biologist and pharmacologist.

He discovered the enzyme lysozyme in 1922 and also published many

articles on bacteriology, immunology and chemotherapy.

Fleming was born at Lochfield near Darvel in Ayrshire, Scotland on

August 6, 1881. He was the third of four children of Hugh Fleming and

Grace Stirling Morton. Hugh died when Alexander was seven.

Fleming

went to Loudoun Moor School and Darvel School, and then for two years to

Kilmarnock Academy. After working in a shipping office for four years,

he was advised by his older brother Tom, who was already a physician, to

follow the same career, and so in 1901, the younger Alexander enrolled

at St Mary's Hospital, London. He qualified for the school with

distinction in 1906 and had the option of becoming a surgeon. Fleming

went to Loudoun Moor School and Darvel School, and then for two years to

Kilmarnock Academy. After working in a shipping office for four years,

he was advised by his older brother Tom, who was already a physician, to

follow the same career, and so in 1901, the younger Alexander enrolled

at St Mary's Hospital, London. He qualified for the school with

distinction in 1906 and had the option of becoming a surgeon.

However, he preferred to join the research department at St. Mary's,

where he became assistant bacteriologist to Sir Almroth Wright, a

pioneer in vaccine therapy and immunology. He gained his degrees with

medals in 1908, and became a lecturer at St. Mary's until 1914.

Then he went on to serve in the World War I as a captain in the Army

Medical Corps and, with many of his colleagues, worked in battlefield

hospitals at the Western Front in France. In 1918, he returned to St.

Mary's.

After the war, Fleming actively searched for anti-bacterial

substances, having witnessed the death of many soldiers from blood

poisoning resulting from infected wounds.

The discovery of penicillin was almost accidental. After returning

from a long holiday, Fleming noticed that many of his experimental

dishes containing various cultures (bacteria) were contaminated with a

fungus and threw the dishes in disinfectant.

When he retrieved one such dish from the disinfectant, he noticed a

zone around the fungus where the bacteria could not seem to grow.

Fleming isolated an extract from the mould, correctly identified it as

being from the Penicillium genus, and named the substance penicillin.

He researched into its positive anti-bacterial effects and found that

it affected bacteria such as staphylococci. At this stage, Fleming found

that cultivating penicillium was quite difficult, and that, after having

grown the mould, it was even more difficult to isolate the antibiotic.

It was then that he was able to enlist the help of Ernst Chain and

Florey, the team which went on to win the Nobel.

|

The Penicillium notatum fungus |

These developments in 1928 mark the start of modern antibiotics.

Penicillin had changed the world of modern medicine by introducing the

age of useful antibiotics; it has saved, and is still saving, millions

of lives all over the world.

Some estimates place the number of lives saved by penicillin around

200 million. It is due to these reasons that the discovery of penicillin

had been ranked as the most important discovery of the millennium by

many reputed magazines, at the approach of the year 2000.

Fleming also discovered very early that bacteria developed antibiotic

resistance whenever too little penicillin was used or when it was used

for too short a period. He cautioned about its use in his many speeches

around the world; he warned not to use penicillin unless there was a

properly diagnosed reason for its use, and that if it were used, never

to use too little, or for too short a period.

Fleming has won many awards such as Fellowships from many recognised

universities in Europe and USA. He served as President of the Society

for General Microbiology, and was an Honorary Member of almost all the

medical and scientific societies of the world. He was knighted in 1944.

In 1915, Fleming married Sarah Marion McElroy of Ireland and had a

son, who later became a general medical practitioner. After his wife's

death in 1949, he was married again in 1953, this time to Dr. Amalia

Koutsouri-Voureka, a Greek colleague at St. Mary's.

Dr Fleming died suddenly of a heart attack on March 11, 1955 at his

home in London. He was cremated and his ashes interred in St Paul's

Cathedral a week later. |