The

coming of English The

coming of English

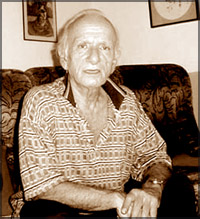

by Carl Muller

Just a few centuries ago, the English were "foreigners" from the

Continent. They came to the Isles as successive races of conquerors and

laid down the foundations of the British character and the language we

now speak, read and write.

First, as we know, came the Celts - a brilliant and imaginative race

who are the forbears of today's modern Irish and Welsh. They were

followed by the Romans in 55 B. C., the Anglo-Saxons in 449 A.D., the

Danes in the ninth century and the Norman-French in 1066.

It was from the German tribe, the Saxons, and their neighbours, the

Angles (that gave us the word "English") that the English language

derived a great of the common words.

It may be quite incredible to know that one out of every 25 words

frequently used in English constitute a quarter of all spoken and

written English, stretching from "the" (the most common) to "have" and

"at". All these words are of Saxon origin.

The Normans, on the other hand spoke a modified Latin, and we find

their contribution to English in words like "beautiful", "magnificent',

"splendid", "recognize," "remember", and "hesitate".

The Anglo-Saxon period was from 449 to 1066. This race came to

England as pagans, and their main contribution is seen in the names by

which we still designate the days of the week. "Sunday" and "Monday"

tell us that the Anglo-Saxons did, at some time, worship the sun and the

moon. The Anglo-Saxon period was from 449 to 1066. This race came to

England as pagans, and their main contribution is seen in the names by

which we still designate the days of the week. "Sunday" and "Monday"

tell us that the Anglo-Saxons did, at some time, worship the sun and the

moon.

In "Tuesday" is preserved the name of Tiw - an evil deity.

"Wednesday" is the day of Wodin, the Teutonic Mars; "Thursday" of Thor,

the god of thunder, "Friday" of Freya, the northern Venus and goddess of

peace, joy and fruitfulness; and "Saturday" of Saetere, a water deity.

This last seems only natural because these primitive Saxons had come

to a live in a land surrounded by the sea and subject to much mist and

rain. It is the language that the Saxons brought to England that is the

English we read, write and speak today, and we must mind that it was a

dialect of German.

But also, when the Saxons landed at Ebbsfleet, England, they had a

literature - not written but transmitted by word of mouth. It is from

the fragments of this literature that still exist, that scholars have

been able to construct a picture of the lives of the early Saxon "scops"

or poets. What was such a poet like? He was happiest, harp in hand,

chanting in the drinking halls before warrior chiefs. He would be

listened to and rewarded with applause and ale.

One such song is the greatest of Saxon poems - "Beowulf" - that has

come down to us and to our day. "Beowulf" is an epic of 3,178 lines. Let

me give you one verse that tells of the death of Beowulf;

Neigling was broken; old and grey-headed,

Beowulf found in his sword no salvation.

The fangs of the worm seized the throat of the hero;

And welled forth in waves Beowulf's life-blood.

But Weglaf was worthy; his sword smote dragon

And Beowulf's dagger divided the demon.

Kinsmen and athelings, they cast forth the spirit.

Thus Beowulf perished, undaunted, unvanquished.

You will see how "Beowulf" was based on alliteration and not on rhyme

- and this verse form persisted as the standard of English poetry until

the coming of Chaucer. I might add that in the verse quoted, "Neigling"

means big sword, and "Athelings" are princes.

During the late Anglo-Saxon period, literature was produced and

preserved by the monasteries that had been established by Roman

missionaries in the early Christian era.

We thus have Bede the Venerable who lived circa 673 and was later

called "The Father of English Prose". He left for us "An Ecclesiastical

History of England" written in Latin, and which gave a record of the

times and writers of that day. He mentions Caedmon, a lay Brother who,

later in life, gave the people a paraphrase of the story of Creation, as

well as Old Testament stories.

Another poet, Cynewulf, carried on Caedmon's work, using themes from

the New Testament and early Church history.

It was in this age that Alfred the Great became King of England.

Around him, many legends have been moven, and Alfred was both a writer

and a patron of literature, giving life to a considerable body of

literary work.

****

See your words in print?

Dear readers,

Email your poems and short stories to [email protected] or

post them to "Passionate Pen", Sunday Observer, Associated Newspapers of

Ceylon Limited, Number 35, D.R. Wijewardene Mawatha, Colombo 10.

Please be patient and do not be discouraged if the publication of

your poems/short stories is delayed. Most of the poems which we received

were subject to rejection because they were too long. Please make an

effort to limit your poems to less than

thirty lines and the short stories to

less than 1,500 words, in order

to avoid rejection.

Next week onwards you can look forward to new changes in Passionate

Pen, where you will be able to learn a lot from professional writers.

Sajitha Prematunge |