Fine depiction of contemporary social and cultural setting

Reviewd by C.A. Lenin Divakara

Nihal

P. Jayatunga, the Sinhala creative writer has proved again as a literary

artiste par excellence in his latest novel Siththarakuge Kathawak (story

of a painter) through his intimate portrayal of the characters and the

depiction of contemporary social and cultural setting.

The educated youth of the post 1956 era, aptly called the ‘children

of 1956’, and their idealism, aspirations, their interaction with the

social-economic realities and the cultural resurgence of the era,

provide the backdrop against which the main characters are portrayed

vividly and credibly in the novel. The educated youth of the post 1956 era, aptly called the ‘children

of 1956’, and their idealism, aspirations, their interaction with the

social-economic realities and the cultural resurgence of the era,

provide the backdrop against which the main characters are portrayed

vividly and credibly in the novel.

The four protagonists of the novel are Darshana, Kanthi, Lalani and

Hemasiri. All of them have a similar social outlook, but personally

differ from one another as chalk is from cheese. They interact, creating

an exciting plot structure, with melodramatic qualities. But the plot is

not manipulated by the author who uses melodrama only as a literary

technique to depict the realities of a turbulent era, and to highlight

the idealism of the characters.

Darshana, a revolutionary youth with a broad social outlook, Hemasiri,

rebel turned an exponent of spiritual salvation, Lalani, the radical

feminist painter and Kanthi, the frustrated wife, the old flame of

Darshana form a cross-section of the educated youth, committed and

dedicated to radical social change.

All of them belong to rural Sinhala families in the South of Lanka

and are steeped in Sinhala Buddhist culture.

The author being ‘a child of 1956’ has portrayed, with intimacy, the

characters with their rebellious’ idealism, Buddhist ethos, and romantic

overtures to one another.‘Siththarakuge Kathawak’ is a unique

contribution to contemporary Sinhala literature in that, it explores the

inner world of the educated rebels and the broader social - economic,

and cultural realities which they encounter. Thus, Jayatunga handles

with expertise, the enviable task of striking a balance between the

social reality and the human factor.

The female characters are grassroot feminists each in her own way in

the sense, they successfully overcome the social barriers, the taboos

and inhibitions, without being promiscuous and freely mingle with the

opposite sex.A pertinent question that might be raised by an enlightened

reader of the novel whose two protagonists are painters as well as

rebels, is that whether their revolutionary politics influenced their

works of art and vice versa. Do their political views and their

commitment to the cause of social justice influence their creations?

Conversely, do their aesthetics, influence, their role as political

activists? Do they consider their respective roles as artiste and rebel,

incompatible? Do they believe in the absolute aesthetic value divorced

from social reality?

The author could have humanised the roles of Darshana and Lalani as

painters and rebels, by portraying them, mutually enriching each role,

that of the rebel with an aesthetically humanising dimension and of the

artist, with revitalising humanising effect.

The author paints a vivid picture of the prison where Darshana

undergoes severe hardships while striking a clandestine intimate

relationship with a fellow female prisoner, Lalani.

This portryal of the bleak environment is juxtaposed with the serene

rural surroundings. Siththarakuge Kathawak’ offers the Sinhala reader a

rewarding experience that broadens his outlook of life and society.

Jayatunga, the literary artiste, strikes a balance between the social

realities of a turbulent era and the human dimension of the characters,

when he depicts with sympathy, exploring their inner world, making the

reading of the novel an interns experience for the reader.

The novel is an outlet for the writer’s creative artistry as indicted

by the rich, sensuous imagery and the lucid, literary style.

To Ujiji, Kigoma and Laket Tanganyika

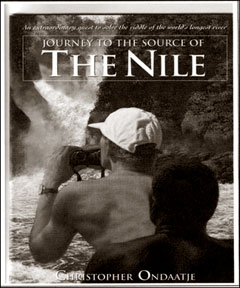

Reviewed by Carl Muller Part 3

As Christopher says: “When we set out from Zungamero, I had hoped to

cover the distance (to Lake Tanganyika) much more quickly... We left

Bangamoya on October 25 and arrived at Lake Tanganyika on November 1...

The trip... (was) a difficult slog... we detoured and backtracked

ceaselessly, trying to identify some of the more elusive portions of

Burton’s trail.”

|

Journey to the source of the Nile |

They went south to Mikumi, then to Miyombo and Kilosa. They passed

through Ulaya, meaning “Europe” because the first person to camp there

was a European. They found no throughway from Kilosa through the Rubeho

Mountains to Dodoma, so backtracked to pick up the Miyomba-Dodoma road.

They made sure that they were always in sight of a river tributary,

making their way over the foothills of Rumuma, and readied to cross the

Rubeho mountains. Christopher says: “We heard on the radio that there

was fighting in Zaire near the border of Rwanda and Burundi.” Moving

into the Rubeho foothills they met members of the Wagogo tribe. They had

reached Ugogo - typical settlements of flat-topped thatched houses. He

also tells of their encounter with two police officers and two

politicians who drove up while he was taking pictures of children and

their schoolhouse. Rather than confront Christopher, they began to

threaten Pollangyo.

“You are selling our people for money! You are holding up the poor of

Africa to the ridicule of the rich by helping the white man to get

photographs!”

A roll of film was confiscated, but the team got away well enough,

lucky that they were not held in detention.

What delights the reader is the careful and considerate manner with

which Christopher “fills in” so to say. As an example, he tells of

arrival at the village of Mpwapwa; the village boutiques, the women

carrying bags of peanuts. This is what he says:

The peanut or “ground nut” as it is usually called in Africa, has a

curious history. One of the chapters of that history is the story of the

infamous British “Ground Nut Scheme” of the 1940s. This was a 25 million

pounds plan to cultivate 1.2 million hectares of peanuts in the Mpwapwa

region and export them via a new port connected by a railway to the

peanut fields - the port and railway to cost an additional 5 million

pounds. However, the scheme collapsed because the planners failed to

take into account the realities of the soil and climate of the Mpwapwa

region, and the difficulties of introducing mechanized cultivation.

Perhaps they would have been more successful if they had read Burton. He

begins his description of Ukaranga, the country between the Malagarasi

ferry and Lake Tanganyika by writing, “Ukaranga signified,

etymologically, the “Land of Groundnuts.”

They took the main road to Dodoma, well-paved but rising clouds of

red dust. This is his quick reference:

Dodoma began as a settlement of thatched huts of the Gogo, a tribe

that Stanley called “masters of foxy craft.” The settlement grew with

the arrival of the railway at the beginning of the 20th century. The

railway stations became the centres of the towns that lined the old

caravan routes. That is where the markets and shops were established

Dodoma dwindled considerably during the First World War, when 30,000

people died of starvation in a famine caused by the misappropriation of

food supplies by the Germans and the British. In the 1970s the Tanzanian

government declared that Dodoma was to replace Dar es Salaam as the

capital in the 1980s, but this still has not happened. “Idodomya”

meaning “the place where it sank” and referring to an elephant that got

stuck in the mud of a Gogo washing hole, is a phrase that gave the town

its name on German maps. The name, like the elephant, stuck.”

Dodoma’s main modern importance came with the reform plans of Julius

Nyerere, the father of Tanzanian independence. He used Dodoma as a pilot

programme for his concept of communal life, which had three phases.

First, Nyerere attempted to create self-reliant agricultural socialist

villages whose residents held their property in common and worked

together for the good of the village... The villages were in large parts

modelled on Chinese communist villages... When this scheme resulted in

the enrichment of some farmers at the expense of others, a second phase

began under which the state assumed direct control and attempted the

resettle most of the people living in rural areas into planned villages

with modernized services. But this latter scheme proved to be too

expensive and also failed. Finally... the whole rural population was

regrouped into larger units through a compulsory policy which came to be

known as “villagization.” This process resulted in the elimination of

traditional tribal rule, with predictable resentment. Villagisation was

ruthlessly enforced, and in the long run, might still prove to be

beneficial.

West of Dodoma, the railway town of Manyoni and Tabora. A comment:

We passed numerous villages, and along the way were reminded that the

Swahili word for white man is “mzungu”, which comes from “mzungu kati”

meaning “wandering around in circles going nowhere.” I was beginning to

understand why.

At Kazi Kazi: I was again reminded (of the whimsical literal

translations Burton provided for place names) when we reached Kazi Kazi,

a small railway station whose name means “work-work.” I was never really

sure whether this name implied colonial criticism of the natives or

native criticism of the colonials.”

Reaching Karagasi: At the sight of date palms, I knew this was the

old caravan route, and I felt we were on the Burton-Speke route to

Tabora.”

Passing Tabora: ...we met three Sukuma maidens who had come a long

way to get water. “Aren’t you afraid of being eaten by lions?” we asked.

“No,” they answered; “the lions are looking for animals, not people!” An

interesting answer.

On the way to Kigwa they heard radio reports of an ebola outbreak in

Zaire: This viral infection ruptures cell walls, beginning with those of

the internal organs, and turns the victim’s body into a sack of bloody

pulp.

It took 5 1/2 days to reach Tabora firm Bagamoyo. Christopher was now

anxious to get to Ujiji on the shore of Lake Tanganyika. They crossed

the Malagarasi river to reach the final station in the Fourth Region of

Burton’s trek. They were now near Ujiji and the eastern shore of Lake

Tanganyika.

Another comment: Those who had come from Zaire were fleeing the

conflict between the ruling dictator, President Mobutu, and the rebel

leader Laurent Kabila. The refugee situation was greatly worsened by

conflict between warring factions of Tutsis and Hutus, which had

resulted in the further flight of hundreds of thousands of Hutus from

neighbouring Rwanda.

The refugees are the result, not the cause, of the strife - the

result of political upheaval and of genocide, stemming in turn from

colonial interference in Africa, from the transition to undemocratic

forms of independence, and from tyranny and greed.

Refugees are big business in Africa. The Western world is being held

to ransom by the various countries to which refugees flee. Tanzania, for

example, will not always admit the refugees unless Western countries pay

the government for costs and administration. When payment is assured a

certain number are allowed in and given refugee status. It is not a

simple humane act. It is a business deal. Only when the money is

actually paid do the white UN vans come into play to transport refugees,

to set up the camps, to provide medical services and so on. The host

countries make enormous financial demands on the Western countries. Some

of this money trickles down to the refugees. Most of it, however,

usually goes to the people organizing food and shelter for them. The

refugees were being held of shore not simply because of lack of space.

It was financial blackmail.

Having crossed the Malagarasi, they entered the Fifth Region of

Burton and Speke’s journey to Kalenga and Kidawe and to catch the first

sight of Lake Tanganyika. They drove into Ujiji - one of Africa’s oldest

market villages. Let me now tell you of Christopher’s impressions:

It is colourful, bustling, commercial centre. The majority of the

population is from the Ha tribe, although Arab influence is seen in the

architecture.

Burton and Speke, the first Europeans to see Lake Tanganyika, arrived

in Ujiji in February 1858, and immediately started exploring the waters

of the lake.

Twenty-three years later, in 1871, Livingstone also made his way to

Ujiji, at that time the terminus for most caravans from the coast. It

was here that the historic meeting between Stanley and Livingstone took

place. Both the name of Livingstone Street and a 1927 plaque donated by

the Royal Geographical Society commemorate the event. In Ujiji we headed

straight to the Livingstone Memorial. It stands on the spot where

Stanley met the famous explorer, but the beach and the lake front have

receded considerably.

They heard stories about the refugees in south-western Tanzania who

were pouring in from Rwanda and Burundi. Even in Kigoma, refugees made

their way across the lake from Zaire, seeking escape from the political

turmoil in that country.

There were crocodiles and hippos clearly visible in the water. It is

well known that there are more deaths caused by hippos than by any other

animal in Africa. Despite their placid appearance, they are extremely

aggressive and attack boats and charge people on river banks.

Christopher’s comment:All were Hutus, and all had arrived from Zaire.

It really was a pitiful sight. The police were everywhere, searching the

refugees for guns and ammunition. If not confiscated by police, weapons

were traded for money or provisions, usually to rebel Tanzanians.

Arms were also sought by refugees planning to return to Burundi to

seek revenge against the Tutsis. Once searched, the refugee boats

were... checked again and their occupants were registered as refugees,

but only after the required guarantees from the international community.

Refugees cannot settle in Tanzania anywhere but in the refugee camps. It

was heartbreaking to see tired, sad-eyed, dejected families with small

children huddled amid their possessions, mattresses, bundles of clothes,

bicycles. Everything - people and goods - piled into the open slender

boats.

They cruised in a boat up the east coast of Lake Tanganyika - seven

fishing villages and boatloads of refugees waiting offshore at each. As

he says:

Our trip up the east coast took four hours and went as far as the

Burundi border. Because of the refugees, there was a disturbing quality

to our explorations. There was an uneasiness to Burton and Speke’s

experiences at Lake Tanganyika too. It was there that their unlikely

partnership began to founder, dashing forever any hope that they would

identify the source of the Nile together

Part 2 appeared on August 24,2008.

Sirith Maldama

‘Sirith Maldama’ which was written way back in 1895 by Muhandiram M.

L. Silva, a teacher has been reprinted by the President’s Security

Division under the guidance of President Mahinda Rajapaksa. Steps have

been taken to distribute the copies free to children across the country-

to schools and Dhamma schools with the intention of inculcating good

habits in them. Those who are interested could obtain a limited number

of copies by writing to (along with your contact no) Commanding officer,

President’s Security Division, President’s House, Colombo.

Book Festival 2008 at SLECC, Colombo

Book Festival 2008 which commenced yesterday will go on till

September 13, 2008 to coincide with the Literary Month at Sri Lanka

Exhibition and Convention Centre.

This event being conducted under the patronage of Madam Shiranthi

Rajapaksa, apart from inculcating the habit of good reading among the

children and youth in our country, will create a unique platform to

create awareness on Thalassaemia prevention programme.

Organisations such as Sri Lanka National Book Development Council,

Department of Mass Communication, Department of Education Publication,

Departments of Examinations, State Printing Corporation, Central Bank of

Sri Lanka etc. will participate at this exhibition along with a number

of statet and private bookshops and related industries.Attractive

discounts will be offered by the exhibitors along with various

activities to celebrate the Literary Month. An exclusive clinic will be

operative for pre-diagnosis of Thalassaemia, a topic that most people

are not aware of, whilst this opportunity will create a forum for

awareness, causes leading to this illness and how to save our future

generation from this deadly disease.

New on the shelf

Asoka Palliyaguruge’s The Bower Bird and Other Poems , an anthology

contains forty poems written by her based on her personal experience and

confidences her friends shared with her. Illustrations are by Thilak

Palliyaguruge. As Kalakeerthi Ashley Halpe mentions in the Foreword

Palliyaguruge’s “poems capture the pains, pathos, and comforts of

everyday experiences, others give glimpses of much loved landscapes,some

are thumb-nailed morality sketches.All in all she achieves a generous

human presence.

Book launch

Dos Nathi was Nathi kos

‘Dos Nathi was Nathi kos’ a research study on Jak fruit written by

Nihal P. Abeysingha will be launched at National Library and

Documentation Board Auditorium, Colombo 07 on September 8 at 3 p.m.

Peralikara Pasala

R. P. Wijesinghe’s Sinhala translation of Arkady Gaidar’s popular

novel The School entitled Peralikara Pasala will be launched at

Dayawansa Jayakody Book Exhibition hall, Ven. S. Mahinda Mawatha,

Colombo 10 at 10 a.m. on September 9.

|