|

Literary criticism:

Complex responsive endeavour

|

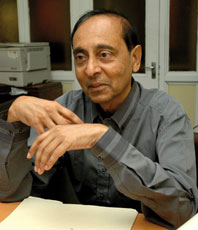

Prof. Wimal Dissanayake |

In an exclusive interview with Montage,

Prof. Wimal Dissanayake expresses his views on literary criticism in

general and literary criticism on Sinhala writings in particular. Given

the recent controversy over qualification of the so called judges in the

award committees and their dubious selection of literary works for

awards, the interview offers fresh and thought provoking views which are

of lasting value in uplifting the literary criticism in Sri Lanka.

by Ranga CHANDRARATHNE

Q: We want to seek your wisdom and knowledge on literature, cinema

and art and want to discuss on literary criticism in general and in

particular on Sinhala writings, focusing on key issues and trends. How

would you define literary criticism?

A: Literary criticism represents an important activity related to the

understanding and evaluation of literary texts. T.S. Elliot once said

that it is as common as breathing. However, good, insightful literary

criticism is rare. What are the important steps in literary criticism?

First we need to pay very close and sustained attention to the words on

the page. This is what, for example, the New Criticism demanded.

However, closer attention to words on the page by itself is not

adequate. We saw the limitations of this approach in the efforts of

those who practised New Criticism

In addition to the focus on the words on the page, we need to locate

the given literary text in its proper social, cultural, political,

ideological contexts. This demands great powers of acuity as well as

historical understanding and cultural imagination. In addition, the

critic must be able to uncover the ideological forces at play in a

literary text. Fredric Jameson talked about the political

unconsciousness of texts. Modern literary theorists refer to a form of

literary criticism termed symptomatic reading. This constitutes an

effort to read against the grain and uncover the ideological symptoms of

a work.

Another important aspect, one that is largely neglected in modern

literary theory, is the capacity to empathize, feel one's way into a

text. The ancient Sanskrit theorists employed the term 'sahruda' to

signal this attribute. So, literary criticism is a complex responsive

endeavour that calls into play a plurality of forces, intentions, and

aptitudes.

Q: What are the qualities of a good critic and could a creative

writer also function as a critic?

A: As I stated earlier the ability to respond sensitively to the

verbal texture of a given text to feel one's way into it, situate it in

large social and historical patterns is essential for a critic. These

qualities are also vital for creative writers. A good critic is a good

reader. The Argentine writer Borges once remarked that good readers are

rarer than good writers.

Traditionally, literary criticism has played an ancillary role to

literary creativity. However, as a consequence of the work of modern

literary theorists such as Harold Bloom and Geoffrey Hartman, the idea

of literary criticism has gained recognition. In addition, when you read

the critical writings of a critic like George Steiner whose writing is

marked by verve and poetic elegance, you begin to appreciate the

creative potentialities associated with literary criticism.

Q: What are the major schools of criticism dominant at global level

today?

A: There are many schools of literary criticism operative in the

modern world. Among them Liberal Humanist Criticism, New Criticism,

Phenomenology, Structuralism, Deconstruction, Poststructuralism,

Postmodernism, New Historicism, Cultural Studies, Feminist Studies,

Postcolonial theory are extremely important.

Each school has its own preferred assumptions and approaches as well

as strengths and limitations. Q: What are the dominant literary theories

that have come up in age in recent decades making a global impact?

A: Among the dominant literary theories that have emerged in recent

times and which have exerted a worldwide influence, I would include

Deconstruction, Poststructuralism, New Historicism, Feminism and

Postcolonial theory. When I travel in countries like India and China and

Japan, these are the theories that seem to exercise the greatest impact

on the academic imagination.

Q: These days we often hear about postcolonial theory or theories.

Could you give us a brief summary and key literature in this regard?

A: Postcolonial theory has many faces. The most important face has a

large Indian component. Literary theorists such as Gayatri Spivak and

Homi Bhabha, with whom I have had the good fortune to have extended

discussions, have shaped Postcolonial theory in important and complex

ways.

Postcolonial theory seeks to understand the impact of colonialism on

textual production and the way issues of representations operate in

postcolonial societies.

When we discuss Postcolonialism, the central text that invited our

attention is Edward Said's treatise "Orientalism". Drawing on the work

of Michel Foucault, it demonstrated vividly how knowledge and power are

intertwined and how European powers through misrepresentations and

de-valorizations of oriental peoples sought to control and dominate

them. In recent times, Postcolonial theory has become a growth industry

generating in the process its own forbidding jargon. There are literally

thousands of PhD thesis being written at this very moment in North

America using the analytical techniques and critical lexicon associated

with postcolonial theory. Postcolonial theory has opened up several

important avenues of inquiry. It has also created its own pitfalls.

Q: Could western scholars who are not acquainted with Eastern

literary theories, such as "rasa" or features of major poetics of

ancient poets like Kalidasa's work such as Raghuvamsha ("Dynasty of

Raghu") and 'Kumarasambhava' ("Birth of the War God"), as well as the

lyrical "Meghaduta" ("Cloud Messenger") could come out with theories

with universal values?

A: You raise a very important question. Western literary theorists,

without an adequate understanding of say 'rasa vada' or 'dhavani vada'

can produce theoretical texts that can claim to universality. As a

matter of fact, what has happened is that Western theorists seek to give

a universal applicability what are principally outgrowths of Eurocentric

modes of thinking and feeling.

It is indeed a great shame, that not only Western critics but also

Asian critics are increasingly becoming victims of a kind of cultural

amnesia. They seem to forget or choose to ignore the rich store house of

Asian creative and critical texts. Indian, Chinese, Japanese literary

traditions merit close attention.

Q: Could you give us a brief overview of the evolution of Sinhala

literary criticism and their relevance to examine modern Sri Lankan

writings?

A: The two commanding influences in the emergence of modern Sinhala

literary criticism were Ediriweera Sarachchandra and Martin

Wickremasinghe. Sarachchandra sought to combine the cumulative wisdoms

of Sanskrit aesthetics and New Criticism. He was responsible for

clearing a pathway for evaluation and modern novels. He invoked the

concepts of believability, an aspect of realism, and psychological

complexity, in his endeavour. He was much influenced by liberal

humanistic thinking and analytical philosophy.

Martin Wickremasinghe, on the other hand, thought in terms of a

Sinhala form of criticism that drew on Buddhist texts and Buddhist

humanism. He took a broadly culturalist approach to the understanding of

literature. Very early on, he saw the value of anthropology as a

significant field of exploration and an important gateway to understand

culturally-grounded textual meaning.

Sarachchandra was a professor at Peradeniya and he influenced the

thinking of many students there including myself. There emerged what is

broadly referred to as the Peradeniya School of criticism. In later

years the idea of people's literature gained ground. It was influenced

by Marxist thinking. In recent times there have been attempts to apply

newer theories of literature such as Postmodernism not with conspicuous

success. What is needed today is a form of criticism that while being

sensitive to the verbal structures of texts is equally alert to the

historical and social forces inflecting texts. In this regard. Gunadasa

Amarasekera's books such as "Abuddassa Yugayak" and "Nosevna Kadapatha"

are extremely illuminating.

Q: Could we have universal literary theories that are applicable to

any work, anywhere, anytime?

A: You can have universal theories of literature. However, they would

be so abstract and so removed from the historical and cultural life of

texts that their value would be limited. Of course, there are broad

understandings of literature. But what is far more important is the

complex ways in which these broad understandings manifest themselves in

historical and cultural specificities.

Q: For example, do we need to use different literary theories to

understand and appreciate the work of short stories of Martin

Wickramasinghe, G.B. Senanayake, Gunadasa Amarasekara, K. Jayathilake,

Erawwala Nandimithra, Jayathilake Kammalweera or for that matter some

new writers emerging from Australia or elsewhere writing their new or

diasporic experience?

A: In assessing the kind of short stories written by the kind of

writers you have identified while being aware of general theories of the

short story, we must also be mindful of the peculiarities and

distinctiveness of writers. For example, Gunadasa Amarasekera writes in

a certain style, while say, Aijth Tilakasena. or Arawwala Nandimithra or

Ranjith Dharmakeerthi or Simon Navagaththegama will write in a different

representational register. We need to pay attention to their

differences. For example, I wrote a forty-page Preface to Arawwala

Nadimithra's Collected Short Stories. In it, I sought to focus on what

is distinctive, both strengths and weaknesses of Nadimithra's work.

Q: We often hear the story that there exist low standards of judging

literary products of Sri Lanka. You may have heard recent debates about

the merits and demerits of the work chosen for national literacy awards

in 2009. Could we have universal and 'fit for all' standards to judge

literary work?

A: The problem with much of modern Sinhala literary criticism is the

absence of standards. To be a good critic one's circle of reference has

to be sufficiently wide to accommodate diversities of influences and

textualities. Modern Sinhala literary criticism, for the most part,

lacks the kind of broad intellectual engagement that is pivotal to

production of sound literary criticism. As I stated earlier, we can

apply certain universal norms in assessing Sinhala literary texts. But

what is far more important is the local resonance, as manifested in

cultural specificities, of those global understandings.

Q: Do we have a fair tradition of literary criticism in Sri Lanka and

if not, how can we improve the conditions?

A: Looking back over the past sixty years or so, we can say that we

have succeeded in paving the way for the emergence of a healthy

tradition of literary criticism as reflected on the works of

Sarachchandra, Wickremainghe and Amarasekera. The most productive way of

improving on that tradition is by opening ourselves to modern currents

of thinking while exploring the complex roots of our own cultural

legacy. These two endeavours are united and complementary.

Q: Despite your busy schedule, do you have any plans to write a book

or two in Sinhala or English examining the work of new writers emerging

from Sri Lanka or those who write about Sri Lanka from London, Sydney,

Toronto or Perth?

A: Yes, my latest book of criticism in Sinhala, which is titled ("Satara

Doratuva") will be released this month. It is a series of exchanges

between Prof. Kulatilaka Kumarasighe and myself. Using advanced modern

theory, it explores the four intersecting concepts of author "text"

reader-context. I have another book in English which should be published

some time this year. It deals with the importance of Buddhism as a

positive, creative force in the works of the three of the most brilliant

modern writers of Sri Lanka" Martin Wickremasinghe, Ediriweera

Sarachchandra and Gunadasa Amarasekera. There is a substantial body of

writing emerging among Sinhala diasporic communities.

There is an imperative need to map that body of writing and give it

comprehensible shape. The work of Sunil Govinnage, who lives in Perth,

Australia, is most important among the writings of diasporic writers. If

you take a country like India, a very large number of its most important

writers live beyond its shores. |