Good and evil in Anil's Ghost - Michael Ondaatje's exotic Sri Lanka

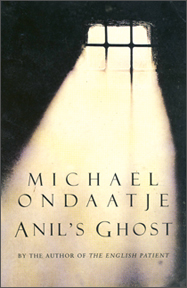

'Anil's Ghost' Michael Ondaatje's first novel, since his Booker Prize

winning work, 'The English Patient' (1992), provides readers a vivid

journey back to author's native country, Sri Lanka. In this novel, the

brutality of the civil war that tore Sri Lanka apart in the mid 1980s to

early 1990s is portrayed through l Ondaatje's standard lyrical prose. 'Anil's Ghost' Michael Ondaatje's first novel, since his Booker Prize

winning work, 'The English Patient' (1992), provides readers a vivid

journey back to author's native country, Sri Lanka. In this novel, the

brutality of the civil war that tore Sri Lanka apart in the mid 1980s to

early 1990s is portrayed through l Ondaatje's standard lyrical prose.

"It is his extraordinary achievement to use magic in order to make

the blood of his own country real," Richard Eder wrote of Ondaatje's

novel in The New York Times Book Review (2000). The Sri Lankan civil war

in the mid 1980s to early 1990s forms a part of the background of the

novel.

In this paper, my aim is to provide a non-western perspective about

Ondaatje's "country real", and to analyse how he has represented the

clash of good and evil or more specifically, Eastern and Western

cultural values as represented by two main protagonists-Sarath and Anil.

It is evident that Ondaatje purposely constructed these two characters

with opposing behaviour patterns that may be identified as symbols

representing the East and West or good and evil traits respectively. In

other words, Ondaatje attempts to represent two cultural perspectives

and interpretations in the context of what Edward Said has articulated

as Orientalism. In addition to Said's interpretation, I would like to

bring a Buddhist perspective which Ondaatje seems to have grappled with

in Anil's Ghost and to some extent in his latest poetry collection,

Handwriting (1999). However, in this paper, I will not go into details

of this Buddhist interpretation except to suggest a concept that may be

useful to understand the term "good" deeds as found in Buddhist

literature.

|

|

Michael Ondaatje |

Anil's Ghost is a sad tale; a tragedy. What is Ondaatje's intention

of telling this tragedy? Is it simply an account of a Westerner's

observation of the horrors and evils that took place in Sri Lanka during

a time of terror? Is it a representation of Good and Evil or the values

from East and West? Is it a representation of Eastern and Western values

associated with a brutal civil war which engulfed the entire fabric of a

Third World country for over 20 years? In order to address at least some

of these questions, it is important to provide a working definition on

good and evil. This is also important to understand the sub-text and

philosophy of Ondaatje's novel.

Beyond good and evil

Throughout the history of human civilization, various definitions

have been proposed to interpret the notions of 'good' and 'evil'. Of

these definitions, in recent times, Nietzsche's cardinal work, Beyond

Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future, (German: Jenseits

von Gut und Böse: Vorspiel einer Philosophie der Zukunft) has attracted

philosophers and intellectuals alike and has been used as a framework,

particularly the adoption of its terminology to examine and discuss

events associated with the September 11 terror attacks. According to

Nietzsche, good and evil may be interpreted as a question of the

falseness of judgements and to what extent a judgement is

"life-promoting, life-serving, species-preserving, perhaps even

species-cultivating". My intention is to explore Nietzsche's selective

words of embracing a judgment relating to life-promoting and

life-serving purposes that I have identified in Ondaatje's Anil's Ghost.

I will first attempt to provide a working definitions of the terms;

good and evil. Providing a definition of good and evil is a complex task

as one could introduce theological, philosophical, cultural and even

ethic-centric interpretations.

For the purpose of this article, I would embrace a simple view on

these two contrasting phenomena by adopting "good" as acting in an

altruistic manner, caring for others more than one's self, and acting as

a "Good Samaritan" or other generic benevolent behaviour. On the other

hand, "evil" will imply the opposite of "good" but may also carry other

connotations, including murder, violence, or behaving with political or

religious ideologies that may destroy human lives if the end justifies

the means.

I would also like to link these definitions into a broader category

of East and West which has a specific way of looking at individuals or

nation state actions through a set of values commonly categorised as

"developed" or "under developed" societies. For example, in the context

of Anil's Ghost, the United States of America is represented a

"developed" society whereas Guatemala and Sri Lanka are categorised as

"under-developed" and as places where ongoing human atrocities take

place.

These definitions can be viewed as an attempt or representation by

Ondaatje to look at his native country as an Orientalist. I use the

notion of Orientalism here to denote the discipline constructed by

Edward Said in his book, Orientalism (1978). Although Said's study

limits Orientalism to a discussion of how English, French, and American

scholars have approached the Arab societies of North Africa and the

Middle East, in this paper, I use the term Orientalism in a broader

sense, primarily to suggest how a Western author might view a remote

"exotic" culture such as Sri Lanka, and in particular to look at good

and evil in a so-called third World country from a western perspective.

The female protagonist of Anil's Ghost is a forensic pathologist,

Anil de Tissera, and she left her native country Sri Lanka, at the age

of eighteen to study medicine in the United Kingdom. Anil specialised in

forensic pathology and then moved from the United Kingdom to the United

States.

The novel begins with a brief prologue set in Guatemala, where Anil

is participating in a forensic anthropological project. The prologue

describes an encounter with a woman who visits the project site to find

out whether the bodies Anil and her team are working on belong to her

missing relatives. In my view, this is a clever literary technique

deviced by Ondaatje to symbolise the detachment and foreignness

projected by Anil as a Westerner. The prologue also provides a stark

dichotomy between the woman from Guatemala and Anil as representative

symbols of two worlds: the Developed and a Developing world.

Extra judiciary killings

After 15 years abroad, Anil returns to her native Sri Lanka as a

United Nations consultant to investigate the atrocities associated with

the Civil War. Anil's mission for the United Nations is to find evidence

of government involvement in atrocities including extra judiciary

killings.

The difficulty of this task is the precariousness of Anil's

situation. This is strongly represented as a Western intervention; and

the Sri Lankan government's reluctant agreement to the mission to

provide Anil with logistical support. Anil is assigned a local

counterpart, Sarath Diyasena, whose real expertise is sixth century

archaeology. Sarath is the government designated 'agent' who accompanies

Anil on her journeys to various remote parts of Sri Lanka in search for

evidence of terror. In her search for evidence of terror, most

Westerners may identify that Anil's outlook as a search for "evil". In

my view, these journeys are the media Ondaatje uses to provide multiple

channels to deliver vivid descriptions of his native land, its mystical

history, archaeology and above all, the terror and atrocities in a time

of uncertainty.

Clash of two cultures

One of the crucial features of the novel is the representation of a

clash of two cultures, the East and West. This is represented through

the interaction between the main protagonists; Anil and Sarath. From the

very first moment they meet, Ondaatje interjects two distinct cultural

values associated with good and evil. Anil undoubtedly represents the

western values and epitomises good. Because of Anil's western training,

she has gone through a metamorphosis. She has not only changed her

native values but also conditioned by foreign (western) codes:

"In her years abroad, during her European and North American

education, Anil had courted foreignness ... she felt completely abroad.

(Even now her brain held the area codes of Denver and Portland.)"

(Ondaatje, 2000:54)

When Anil left Sri Lanka, she was a well-known athlete from a family

with high connections but after leaving the country to study medicine,

she returns as an outsider. When Anil is asked: "You have friends here,

no?" her response is: "Not really" (p10). For someone who is aware of

Sri Lankan customs and values, this is a difficult position to accept;

Sri Lankans of all classes have connections with people and places

everywhere especially in their native country.

Initially Anil displays the detachment of a Westerner on the loss of

life, atrocities and terror in Sri Lanka. Such representations may not

only be interpreted Western, but would not be acceptable to Sri Lankans

who have had to suffer through a civil war in their country for over 23

years.

Ondaatje portrays Anil as a person who is no longer interested in the

human elements behind the tragedies associated with the terror in her

native Sri Lanka because of her acquired Western values. According to

Elder:

"Anil comes with Western-bred investigative passion: the certainty

that facts are there to be unearthed and that truth is to be constructed

out of them." (Eder, 2000).

Anil with her acquired Western mode of thinking always questions

Sarath Palipana's motives and approaches. This is well established

during their first encounter in Sarath's office. As a normal and curious

Sri Lankan, Sarath is interested in Anil's past as she comes from a

well-known Sri Lankan family. When Sarath questions Anil about her past

swimming records, Anil responds with an animosity: "Mr Diyasena ...

let's not mention swimming again, okay? A lot of blood under the bridge

since then." (16). Sarath questions her again in the usual Sri Lankan

manner:

"Are you married? Got a family?"

"Not married. Not a swimmer."

"Right." (p17)

This animosity continues throughout the book, nevertheless, Anil

vaguely displays sentimental patches of humanity towards Sarath. This

includes her reaction to the suicide of Sarath's wife, his lonely life

and his professional commitment to his work as an archaeologist. Anil

develops sympathetic feelings, but continues to behave like an outsider;

a westerner with a detached outlook.

Her only objective is to find the "truth" and "evidence" for her

mission. In other words, Anil's aim is to examine the evil atrocities

take place in a Third World country as a Westerner; an outsider. On the

other hand, Sarath, can see the Western values in Anil's approach to

work and life in Sri Lanka. As articulated by Richar Elder: Her only objective is to find the "truth" and "evidence" for her

mission. In other words, Anil's aim is to examine the evil atrocities

take place in a Third World country as a Westerner; an outsider. On the

other hand, Sarath, can see the Western values in Anil's approach to

work and life in Sri Lanka. As articulated by Richar Elder:

Anil comes with Western-bred investigative passion: the certainty

that facts are there to be unearthed and that truth is to be constructed

out of them. Sarath, a polymorphous spirit and the book's most memorable

figure, cautions that the real truth of his country is ambiguous and

unobtainable. (Elder, 2000)

Sarath perceives Anil's mission in Sri Lanka as an approach adopted

by visiting foreign journalists and reporting local events from a five

star hotel in Colombo:

"You know, I'd believe your arguments more if you lived here," he

said. "You can't just slip in, make a discovery and leave."

"You want me to censor myself."

"I want you to understand the archaeological surround of a fact. Or

you'll be like one of those journalists who file reports about flies and

scabs while staying at the Galle Face Hotel. That false empathy and

blame." (p.44)

The Government agent and Anil's investigation

For Sarath, Anil is no different to any other "outsider" who is

totally devoid of any emotional attachments to her native country.

Sarath's response is his way of comparing the deceitful aspects of

visiting foreign journalists who reports 'events' of atrocities from

their five star hotels

in Colombo. He compares these foreign journalists with Anil. On the

other hand, Sarath also has a commitment to finding the truth. Despite

being labelled as the "government agent", Sarath's contribution to

Anil's investigation highlights aspects of "good" including his

altruistic behaviour and finally sacrificing his life to help assist

Anil to take a reliable evidence away to support her mission in Sri

Lanka.

As part of the evidence gathering exercise of Anil's mission, she

discovers a skeleton with the help of Sarath. Anil names the skeleton

'Sailor'.

There is evidence that the body had been moved from somewhere else

into a secured archaeological site to which only government employees

have access. The skeleton becomes the first specific piece of evidence

disclosing a relationship between government operations and the

suppression of those with opinions differing from the official story.

Anil's challenge is to identify the dead man and determine where he

came from, under what circumstances he lost his life, and how and why

his body had been moved from the place of death to a secured

archaeological site. These questions take both Anil and Sarath to his

old teacher and mentor, Palipana, a once eminent archaeologist who has

now retired to an abandoned monastery and become a recluse.

The encounter with Palipana adds a different slant to the novel. In

fact, a critical reader (with inside knowledge of the country) might

question why Sarath takes Anil to see an archaeologist instead of

another forensic pathologist, someone equipped to assist in determining

the cause of the death of Sailor. On the other hand, it could be argued

that the visit to the old archaeologist is a tactic on the part of

Sarath to avoid (government) sabotage Anil's investigation. This point

is left open and merits different interpretations.

Acquired Western values

The most important aspect of the novel is the 'alienness' of Anil who

has been away from her native country for fifteen years. Anil's parents

were killed in a car crash while she was studying abroad.

The novel does not reveal her interaction with any old friends or

relatives, creating suspicion in the mind of a reader who has insights

into the culture and ways of life in Sri Lanka. Anil's only personal

contact is a meeting with an old servant woman whom she knew as a child.

To a Sri Lankan, this particular aspect of Anil's behaviour is quite

strange and unrealistic. Is it due to Anil's newly acquired Western

values, including a reconditioned memory where foreign area codes are

retained instead of local history, language, culture, or people of her

native country? On her arrival in Sri Lanka the officer at the airport

asks in Sri Lankan English:

"You were born here, no?" Her reply is convoluted: "Fifteen years."

"You still speak Sinhala?" asks the officer. Anil's reply is just two

words: "A little..." (p.9).

This reply in my view summarises Anil's attitude towards her home

country and provides an insight into Ondaatje's orientalist approach to

examine Sri Lanka.

Despite this alienness, Anil's comment to the driver while travelling

from the airport to Colombo is "Maybe drink some toddy before it gets

too late."

Toddy is a local brew, which is not normally consumed by young

people, particularly not a youth of Anil's class! It is strange that a

young person who left Sri Lanka at the age of 18 returns after fifteen

years looking for this particular local brew. In my opinion, this is a

representation of popular culture that Ondaatje intentionally interjects

into Anil's extraordinary journeys in Sri Lanka projecting his ideas of

an exotic country, representing his own native land, as an orientalist.

When Anil is finally interrogated by Sri Lankan officials, just prior

to her escape from the country, it is no one else but Sarath who comes

to her rescue by recovering the evidence for her story - the skeleton

named Sailor - which had been stolen by the Government agents. However,

Sarath's commitment to finding the truth contributes to his premature

death, brought about by the government agents who wanted to create

barriers to Anil's investigation.

At the end of the novel, when Anil finally finds the missing skeleton

- Sailor - and the recorded message from Sarath telling her how to leave

the country safely, her immediate reaction is to listen to his voice and

everything again. There is no sign of emotion:

Anil made the tape roll back on the rewind. She walked away from the

skeleton and paced up and down the hold listening to his voice again.

Listening to everything again.

The key point about the novel is the portrayal of two different

cultural perspectives - East and West - and the difference in values

attached to each perspective by Sarath and Anil. Although Anil does not

see it at the beginning, it is Sarath who finally makes a real sacrifice

to find the truth representing good by sacrificing his own life.

Despite the title and the narratives about Anil, in my view, Sarath's

character is crafted so well that he becomes the dominant protagonist in

the novel. Sarath's character is represented in a manner reminiscent of

the non-attachment qualities of a Bodhisattva (a sage making sacrifice).

There are other important questions to be asked about the narrative

techniques by Ondaatje including questions such as "why Sarath did takes

Anil to meet Palipana? "Have these journeys been used to describe

Ondaatje's "country real?" Are these, an Orientlist's depiction of Sri

Lanka's history and amazing archaeological wealth? What is the

connection between archaeology and human rights investigations? What is

the significance of Sarath's brother, Gamini's life and work? Whose

stories are being told in the novel? Is it the story of Anil and her

diminishing linkages to her native country? Is it the story of Sarath

who finally pays the ultimate price to help a westernised Sri Lankan to

reveal the truth to the West?

Despite all these difficult questions, Michael Ondaatje has once

again delivered a great piece of work which is rich in poetic prose. The

language in which it is written is as good as Ondaatje's poetry, leaving

the reader to digest the sadness, the mysteries and beauty of a sad

tale, which he tells as a gifted novelist. There is indeed a

representation of Eastern and Western values in equal portion in this

novel, where "Ondaatje tells us a fascinating story intertwined with

past and present of this island where 'the darkest Greek tragedies [are]

innocent compared with what is happening...' there." (Govinnage, 2000).

However, Michael Ondaatje's conception of history of Sri Lanka is an

integration of many ingredients, developed around two cultures that he

has inherited, and linking their historical, social, literary and

political parameters but have projected these as an orientalist. Much of

the ingredients chosen to write the novel can be categorised as

Ondaatje's personal history of his native country, which may be not

considered "real". I emphasised the word 'real' in summation that the

Booker Prize winning novelist, Michael Ondaatje has represented Sri

Lanka Anil's not only as homage to his homeland but may be as a

documentary written from Canada. Despite the long list of people, he has

interviewed for during the research phase of the book, Anil's Ghost

should be read as a novel and not as a historical documentary

representing a sad phase of Sri Lanka's history.

(This article is based on a presentation of a conference paper at

Western Social Science Association 49th Conference held in Calgary,

Alberta, Canada, April, 2000).

|