In search of a new constitution

by M.A.Q.M. Ghasszli

|

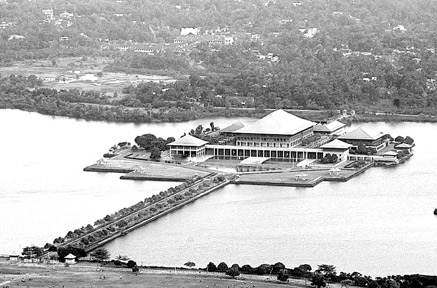

The Parliament complex at Sri Jayewardenepura

|

Half a century and half score into independence from imperialist

dominance, Sri Lanka is still in debate for the adoption of a

constitution. During the course of these long years the Sri Lankan

bodypolitic had failed. In the guidance to governance, emotions had

taken the better of good reasoning, and the nation has not merely failed

to progress, but retarded in every direction until it came to the core

end of disintegration and chaos.

An incredible victory by the armed forces of the country, a miracle

when looked at in retrospect, over the forces of separation and

disintegration has re-created for the whole country a new field of hope

and enthusiasm. The state now requires a well constituted set of

principles, a true form of hope and encouragement for all sections of

the people, setting aside "passions and un reasoning emotions to devise

such freedom as would give every group equal opportunities for growth

and the sensation of freedom and equality"(1) The whole nation is now

agog with the idea of a new and suitable constitution.

Conventions

What indeed is a constitution ? It may be stated , without claim to

precision that a constitution is a collection of fundamental laws and

shall include practices, though unwritten, collectively known as

conventions that determine and guide the affairs of government and its

relationship with the people.

Expressions and explanations of the term 'constitution' have been the

subject of much discourse throughout the preceding ages and their

collection has formed volumes of legal literature. Prof. Wade in his

book 'constitutional law' seeks to explain without defining the term

constitution as: "By a constitution is normally meant a document having

special sanctity ,which sets out the framework and the principal

functions of the organs of government of a state and declares the

principles governing the operation of these organs". Expressions and explanations of the term 'constitution' have been the

subject of much discourse throughout the preceding ages and their

collection has formed volumes of legal literature. Prof. Wade in his

book 'constitutional law' seeks to explain without defining the term

constitution as: "By a constitution is normally meant a document having

special sanctity ,which sets out the framework and the principal

functions of the organs of government of a state and declares the

principles governing the operation of these organs".

Of special interest to the Sri Lankan context is Wade's stated

exclusion from the constitution document, of detailed rules upon which

depend the working of the institutions of government. "A constitution

does not necessarily or usually contain the detailed rules upon which

depend the working of the institutions of government.

Legal processes, rules for elections, the mode of implementing

services provided by the state, so far as these are matters for

enactment are to be found , not in the constitution but in the ordinary

statutes made by the legislature within the limits set by the

constitution itself".

Speaking of conventions Wade states as follows: "Conventions serve to

attune the operation of the constitution to changing conditions, and

thereby to avoid, in the main, alterations to a written document which

is designed to be permanent in its operation.

Traditionally the legislature, executive, and judiciary attract the

core of the laws that are fundamental to the life of a nation. The law

identifies the provisions therein as "the constitution of a modern state

It is suggested that the aspirations of the constitution makers for the

"new Sri Lanka" should be to lay down with clarity, lucidity, and

intelligible form, the fundamental law that is sought to be provided for

the future growth of Sri Lanka, as a true and independent nation of

equal opportunities.

"Realpolitic"

Sri Lanka or Ceylon as it was known in 1948, received a near perfect

constitution authored by the late Sir Ivor Jennings, who was the

foremost exponent of the law of the constitution in his time. This

constitution was repealed and replaced by the 1972 constitution.

As main changes the latter declared the nation to be a "Republic" and

abolished the 2nd chamber. Both these changes are cosmetic in nature and

particularly the abolition of the 2nd. Chamber had nothing to offer for

better governance and had no impact on the "Realpolitic" of the

republican state of Sri Lanka, as the nation came to be thereafter

called.

The new constitutional document made the abysmal error in seeking to

provide in detail the working rules of the courts and other government

institutions as articles of the constitution. This error was

meticulously followed by the 1978 Constitution.

The difference between the two constitutions was that the 1972

constitutional document was motivated by "passion and unreasoning

sentiments" that the constitution must necessarily be home grown.

However, that the document retained the main provisions of the rules of

government is a sound testimony to the grandeur and perfection of

quality of the 1948 constitution.

The 1978 constitution, as we all know, was a quick fix that destroyed

the several rules of good governance in our system. It introduced an

executive presidential system of government where the president is not

accountable to any institution; neither the parliament nor the courts

had any control over the president.

The Parliament merely became a shadow institution where the members

could talk and talk without any effect on the executive who could do no

wrong. Sadly too the members had no identity vis-à-vis the separate

constituencies in the country. The document was a product of self

aggrandizement of a single individual, who had thought like King Louis

XIV of France who built the palace of Versailles for the luxurious

extravagance and consequent distraction of the provincial rulers of

France from the affairs of the state. This left the king in absolute

power and influence in the affairs of government. The silver lining

however in the rule of King Louis XIV of France was that although he

carved for himself a despotic power of government , he was genuinely

benevolent in his rule.

Coming again to our own backyard, the 1978 constitution borrowed a

glittering but hollow idea of proportional representation in our

parliament. This system had theoretical attraction primarily as opening

representation to all interests according to their strength in the

electorate.

A study was done by the British parliament immediately after the

second. World War and the idea was shunned as unsuitable for a genuine

representative government under the Westminster system. Our experience

of elections after 1978, has amply shown the hollowness of the system.

Rivalry

The people do not know their representatives in parliament and the

members can disown their voters until the next elections. At election

time intra party rivalry abounds and the cost of electioneering makes

the contest for a parliamentary seat prohibitive.

Where the fundamental laws of a nation's government structure alone

form the constitution of that nation, such laws will hardly require

amendments, although special provisions to effect amendments shall

always form a part of any written constitution.

Laws relating to the procedure and functioning of governmental

institutions on the other hand will require constant change both in its

form and functions. For this reason alone the functioning of

institutions should only form a part of the normal and regular

enactments that are amenable to change and amendments as and when

required and according to normal legislative procedure. Such laws shall

always be within the limits of the superseding constitutional law.

The search for a constitution, therefore, should be confined to the

process of identifying and determining the fundamental principles of

government.

The search must determine the form and status of the legislature. It

must define the nature, scope and aspirations of legislation to create

such freedom as would give every group " equal opportunities for growth

and the sensation of freedom and equality." .

It must determine the form of the executive and its accountability to

the people. It must provide for a judicial system that can be

independent fearless and above board. It must also make provisions for

its own amendment, perchance a contingency arises for amendment at any

future time.

Amending or replacing the present constitution must therefore seek to

provide for the manifestation of people's sovereignty by providing for a

legislature of elected representatives, who will represent the will of

the people, and from amongst whom alone the executive will be created.

Such an executive shall always be accountable to the legislature. The

head of the executive so created shall always be from among the elected

representatives and who can command the confidence of the majority of

the house.

A second chamber may be considered. Such an institution with lot of

mitigatory influence can contribute immensely to good government. It can

be a nucleus for a judicial institute of final appeal in the form of the

judicial council of the Privi Council that was abandoned in 1972. A

judicial council of this nature even in collaboration with the SAARC

group of countries could be an excellent provision toward making

justice, much appearing to be done.

The executive presidential system, with unlimited powers in the

person of the president and accountable neither to parliament nor to

courts is an experiment that we can ill afford.

Among the world's well-known constitutional provisions for an

executive president, the powers of the president of the US had attracted

the attention of the constitutional lawyers. Keen interest was expressed

on the claims by both the British parliamentary system and the American

presidential system as to which is the better form of government.

I cannot improve on the classic analysis made by Lord Balfour on the

two systems of administration sometime in the early 20th Century.

"Under the Presidential system the effective head of the national

administration is elected for a fixed term. He is practically

irremovable. Even if he is proved to be inefficient, even if he becomes

unpopular, even if his policy is unacceptable to his countrymen, he and

his methods must be endured until the moment comes for a new election.

He is aided by Ministers, who however able and distinguished have no

independent political status......Under the cabinet system everything is

different. The head of the administration, commonly called the prime

minister ( though he has no statutory position) is selected for the

place on the ground that he is the statesman best qualified to secure a

majority in the House. He retains it only so long as that support is

forthcoming; he is the head of his party.

He must be a member of one or other of the two houses of Parliament

and he must be competent to lead the house to which he belongs.

While the ministers of a president are merely his officials, the

Prime Minister is primus inter pares in a cabinet of which every member

like himself have had parliamentary experience and gained some

parliamentary reputation. The President's powers are defined by the

constitution and for their exercise ...... he is responsible to no man.

The Prime Minister and his cabinet, on the other hand, are restrained by

no written constitution; but they are faced by critics and rivals whose

position though entirely unofficial is as constitutional as their own.;

they are subject to a perpetual stream of unfriendly questions to which

they must make public response,and they may at any moment be dismissed

from power by a hostile vote."

The writer is a former Advocate of the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka.

|