Important landmarks in Latin American cinematography

Over the past few weeks I have been focusing on post-Boom writers of

Latin American fiction. During this time, I have reviewed three

popularised novels, written by some of the most highly acclaimed authors

from the era following the Boom .All of these books have subsequently

been made into films, yet I have concentrated on the novels to

illustrate how new narrative styles were used in 'new novel' literature.

Yet the era following the Boom, which experimented with magical realism,

inter-textuality ( a story within a story and the use of tropes ) and

non-traditional narrative styles, were even more successful within the

film industry.

Cinematography popularised political thinking and made it accessible

to the masses to an even greater extent than the new novels, since

motion pictures tend to reach wider audiences.

Fernando Solanas, Octavio Getino and Gerardo Vallejo founded the 'Grupo

Cine Liberación' (The Liberation Film Group) which was an Argentine film

movement that took place during the end of the sixties.

The 'Grupo Cine Liberación' became linked to the Peronist Left, and

in later years, other films directors (grupo Realizadores de Mayo,

Enrique and Nemesio Juárez, Pablo Szir, etc.) revolved around this

activist core. Ferando Solanas is an Argentine Film director,

screenwriter and politician. His films include 'La hora de los hornos' ,

'Tangos el exilio de Gardel' , 'Sur' , El viaje' , 'La nube' and 'Memorias

del saqueo' and many others.

|

|

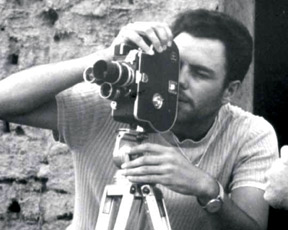

Raymundo Gleyzer |

One of the principles of the 'Grupo Cine Liberación' was to produce

anonymous films as an endeavour to favourize a collective process, to

create a collective discourse and to protect the film makers from

political repression.

According to Lucio Mufud, the collective authorship movement of the

1960s and 1970s was "among other things, about erasing any authorial

mark. It concerned itself, on the one hand, with protecting the militant

creators from state repression. But it was also about having their voice

coincide with the 'voice of the people.' " Another similar group

included the 'Grupo Cine de la Base' (The Base Film Group), which

included the film director Raymundo Gleyzer, who produced Los Traidores

(The Traitors, 1973), and later "disappeared" during the dictatorship .

Both 'Grupo Cine Liberación' and 'Grupo Cine de la Base' were especially

concerned with Latin American integration and neo-colonialism and even

advocated the use of violence as one of the alternative possible means

against hegemonic power .

Since Solanas was at the forefront of this 'Grupo Cine Liberacion'

which revolutionised Argentine cinema in the 1970s, developing its

social conscience and political voice, he and his actors were threatened

by right-wing forces in the 1970s. One of his actors was assassinated

and Solanas himself was almost kidnapped. Significantly he, together

with Octavio Getino, wrote the manifesto "Toward a Third Cinema".

The Idea of a political Third Cinema, as opposed to Hollywood Cinema

and European Auteur Cinema, inspired film makers in many so-called

developing countries, thus moving from any reliance on the film

industries in the United States and Europe. It was a pioneering move

that allowed Latin America to create its own styles and methods of

creating films.

Solanas had studied theatre, music and law. In 1962, he directed his

first short feature Seguir Andando and in 1968 he covertly produced and

directed his first long feature Film 'La Hora de los Hornos', or 'The

Hour of the Furnaces', a documentary on neo-colonialism and violence in

Latin America.

The film won several international awards and was screened around the

world. Solanas has won the Special Jury Award, the Critics Award at the

Venice Film Festival and the Best Director Palme at the Cannes Film

Festival. He was awarded a special Golden Bear at the 2004 Berlin Film

Festival.

Perhaps one of the reasons behind his success as a film maker was the

fact that he often collaborated with other Latin American artists,

rendering his films authentic Latin American creations. He collaborated

with the great tango composer and musician Astor Piazzolla on

soundtracks for several films, including 'El Viaje'. Piazzolla

consistently experimented with other musical forms and instrumental

combinations. In 1965 an album was released containing collaborations

between Piazzolla and Jorge Luis Borges, in which Borges's poetry was

narrated over very avant-garde music by Piazzolla including the use of

dodecaphonic (twelve-tone) rows, free non-melodic improvisation on all

instruments, and modal harmonies and scales.

Piazzolla's nuevo tango was distinct from the traditional tango in

its incorporation of elements of jazz, its use of extended harmonies and

dissonance, its use of counterpoint, and its ventures into extended

compositional forms. By using Piazzolla's music and by referencing him

in films, modern Latin American film makers, such as Solanas break with

tradition (particularly of European origin) again.

I will now review the plot and meaning of Solanas' 'El Viaje', in

order to explore how his films document and comment on Latin American

history, culture and politics and the need to search for an authentic

Latin American identity.

Martin Nunca, a young man living in Ushuaja, a cold southern town in

South America, decides to start a trip looking for his father, an

anthropologist, who was last reported as working in Brazil. Leaving

behind his mother and stepfather, the boy travels north by bike,

encountering scenes of exploitation of the poor, cultural destruction

and abject subjugation to the United States. An example of this is when

a national president, whose surname means "frog", puts on rubber

flippers in order to survey the damage in a flooded city.

The United States is not the only foreign power to which Solanas

implies criticism throughout the film. For example, another flooded town

is filled with people punting through the deluged streets in boats,

cursing the floods and fishing out faeces floating around in the water.

This scene is reminiscent of Venice, which is known to be very polluted

and said to smell like an open sewer. The implication is the new world

neither appreciates nor reveres European traditions in same way that

some Europeans themselves do. The flood also represents crippling

national debt and the filth represents the corruption so intrinsic to

Latin America politics.

'El Viaje''s clear criticism of the state is also exemplified by

portraits of successive dictators being blown off the walls of a

corridor within a freezing college (denoting deprivation on several

levels), where perishing winds sweep the building, howling eerily.

As in other post-Boom Latin American fiction, a good deal of magical

realism is used to create a surreal, strange, yet simultaneously amusing

narrative. It makes it possible to implicitly criticise both collective

powers and individuals, whilst providing a highly entertaining film that

will appeal to the masses in a number of different ways.

|

|

MachuPicchuin Peru |

The cinematography is spectacular and there is much to draw the

viewer on a purely aesthetic level. However, literary metaphors are

introduced when needed in the form of Martin's absent father, the

ancient people of Latin America and Martin's girlfriend to make the film

to work on a more profound level and to speak to the intellectually

minded.

During his journey, Martin comes across many ancient settlements

which have been destroyed by European conquistadors. He subsequently

realises that the ancient citizens have been either totally wiped out or

gradually bred into extinction.

His astonishing journeys take him as far as Mexico, and in so doing,

he discovers many unexpected facts about his own Latin American essence.

One of the key moments for Martin is when he discovers Machu Picchu, the

one city in Peru that was not conquered by the Spanish. The discovery of

the ruins of this beautiful city in the mountains almost comes as a

religious epiphany. Martin subsequently spends a lot of time wondering

what eventually happened to its inhabitants. It seems that the city

takes on a personality of its own as Pablo Neruda's poem is mentioned

via Martin's musings. Neruda also addresses the city as though it were a

person with closely guarded secrets and as though it had the power to

heal and purify, simply for the reason that it managed to avoid being

conquered by the Spanish.

The journey and search for Martin's own identity parallels that of

Latin America. The journey into his own heart leads him into the very

heart of the Latin American continent itself and Martin's search to

understand his situation in relation to his father and to his personal

history leads to the discovery of the history of the land and of its

inhabitants. In trying to escape his own unsatisfactory life in the

southern most tip of the continent, Martin discovers both ancient and

modern corruption and genocide and realises that life is not perfect

anywhere else either. As he travels, he compiles a log book, a collage

of Latin American history in comic form.

This is a rite of passage for him and one in which the epic, the

baroque, the grotesque and fantasies all merge.

The name given to this comic is "discovery", which alludes to the

anniversary of the discovery of Latin America itself. Yet rather than

the anniversary being celebrated, Martin, through the course of his from

Ushuaia to Oaxaca (Mexico), discovers that there is little to celebrate,

since the continent is currently under siege by foreign debt, political

corruption, ecological destruction and hunger.

Fernando Solanas achieved what he set out to do in through 'El Viaje',

which was to present clear criticism of the failed dictatorships, the

subjugation of Latin American to foreign powers, the corruption in the

government and the floundering sense of national identity and future

direction.

He managed this by using unusual narratives and cinematography to

encompass the widest demographic and by making the film accessible on

several different levels. At one end of the scale, the film is highly

entertaining and easy to watch and at the other, it appeals to

intellectual and influential audiences, including those outside Latin

America.

Finally film does offer hope for the future yet suggests that in

order to progress, it is necessary to find and return to Latin America's

indigenous roots, to be reconciled with the past and then to bring

ancient traditions into the present.

It is a most enjoyable film and one that I would highly recommend

both for its entertainment value and for its ability to teach lessons

both from Latin America's past and its current situation.

|